Clare Boothe Luce facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Clare Boothe Luce

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Ambassador to Italy | |

| In office May 4, 1953 – December 27, 1956 |

|

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Ellsworth Bunker |

| Succeeded by | James David Zellerbach |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Connecticut's 4th district |

|

| In office January 3, 1943 – January 3, 1947 |

|

| Preceded by | Le Roy D. Downs |

| Succeeded by | John Lodge |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Ann Clare Boothe

March 10, 1903 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | October 9, 1987 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

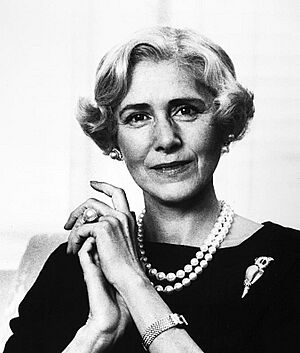

Clare Boothe Luce (born Ann Clare Boothe; March 10, 1903 – October 9, 1987) was an amazing American woman. She was a talented writer, a smart politician, and even a U.S. ambassador. She was also a well-known public figure who believed in conservative ideas.

Clare Boothe Luce wrote many different things. She is most famous for her 1936 play, The Women. This play was special because it had only female actors. She wrote plays, movie scripts, stories, and even news reports from wars. She was married to Henry Luce, who published popular magazines like Time, Life, and Fortune.

Later in her life, Luce became a strong supporter of conservative ideas. She was also very vocal against communism. She supported every Republican candidate for president from Wendell Willkie to Ronald Reagan. She was known for being a powerful and charming speaker, especially after she became Catholic in 1946.

Contents

Clare Boothe Luce's Early Life and Education

Clare Boothe Luce was born Ann Clare Boothe in New York City on March 10, 1903. Her parents separated when she was young. Her father, who was a violinist, taught her to love books. Clare and her older brother, David, moved around a lot when they were kids. They lived in places like Memphis, Chicago, and New York City.

She went to school in Garden City and Tarrytown, New York. She finished school at 16 in 1919, at the top of her class. Her mother wanted her to be an actress. Clare even worked as a stand-in for famous actress Mary Pickford on Broadway when she was only 10. She also had a small part in a movie in 1915. After traveling in Europe, she became interested in the women's suffrage movement. She worked for the National Woman's Party in Washington, D.C.

Marriages and Family Life

At age 20, on August 10, 1923, she married George Tuttle Brokaw. He was a wealthy heir from New York. They had one daughter, Ann Clare Brokaw, who sadly died in a car accident in 1944. Their marriage ended in divorce in 1929.

On November 23, 1935, she married Henry Luce. He was the publisher of Time, Life, and Fortune. After this, she became known as Clare Boothe Luce.

In 1944, her only daughter, Ann, passed away. This sad event led Clare to explore her faith. She became Catholic in 1946. To honor her daughter, she helped fund a Catholic church in Palo Alto for Stanford University students.

Clare Boothe Luce's Writing Career

Clare Boothe Luce was a very creative and witty writer. In 1931, she published a book of short stories called Stuffed Shirts. Critics praised her sharp humor and stylish writing. She also wrote many articles for magazines. But her greatest talent was writing plays.

Her first play, Abide With Me (1935), was not a success. But she quickly wrote a funny play called The Women. This play had 40 actresses and became a huge hit on Broadway in 1936. It was even made into a successful movie in 1939, also with an all-female cast. Luce earned money from this play for many years. She later wrote two more successful plays, Kiss the Boys Goodbye and Margin for Error. Margin for Error strongly criticized the Nazis.

Clare Boothe Luce was known for her sharp and funny sayings, like "No good deed goes unpunished." She developed her humor while working as an editor for Vogue and Vanity Fair in the early 1930s. She edited works by famous humorists and wrote many funny pieces herself.

War Correspondent and Reporter

Another important part of Luce's writing career was her war journalism. She traveled to Europe in 1939–1940 as a reporter for Life magazine. She wrote about World War II in her book Europe in the Spring. She described the war as "a world where men have decided to die together because they are unable to find a way to live together."

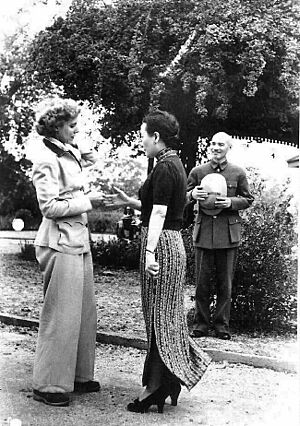

In 1941, Luce and her husband visited China to report on its war with Japan. Her article about General Douglas MacArthur was on the cover of Life the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the United States joined the war, Luce visited military bases in Africa, India, China, and Burma. She wrote many reports for Life and interviewed important leaders like Chiang Kai-shek and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Her ability to be in important places and talk to key leaders made her very influential. She faced dangers like bombings during her travels. Her experiences during the war helped her get a seat on the House Military Affairs Committee when she became a congresswoman.

Clare Boothe Luce's Political Career

Serving in the House of Representatives

In 1942, Clare Boothe Luce was elected to the United States House of Representatives. She represented Fairfield County, Connecticut, as a Republican. Her main goals were to win the war, support the war effort, and work for a better world with lasting peace and jobs at home. She took over the seat that her stepfather, Dr. Albert Austin, had held.

Luce was a strong critic of President Roosevelt's foreign policy. She was known for her sharp comments. In her first speech, she famously used the word "globaloney" to criticize a plan for airlines. She also called for an end to the Chinese Exclusion Act, comparing it to Adolf Hitler's ideas about race. She supported aid for war victims and help for military families.

President Roosevelt did not like her and tried to stop her re-election in 1944. He called her "a sharp-tongued glamor girl of forty." She responded by saying he "lied us into a war."

During her second term, Luce helped create the United States Atomic Energy Commission. She also visited Allied battlefronts in Europe and pushed for more support for American troops in Italy. She saw the liberation of several Nazi concentration camps in April 1945. After the war ended, she warned about the rise of Communism, seeing it as another threat to freedom.

In 1946, she helped write the Luce–Celler Act of 1946. This law allowed people from India and the Philippines to immigrate to the U.S. and become citizens. Luce decided not to run for re-election in 1946.

Becoming Ambassador to Italy

Luce returned to politics in the 1952 presidential election. She gave over 100 speeches to support Republican candidate Dwight Eisenhower. Her speeches against communism helped many Catholic voters, who usually voted Democratic, to switch and vote for Eisenhower. Because of her help, she was appointed as the ambassador to Italy. This was a very important diplomatic job, and she was the first American woman to hold such a high position.

At first, Italians were unsure about a female ambassador. But Luce soon won over many people with her support for their culture and religion. The country's large Communist group, however, saw her as interfering in Italian affairs.

Her biggest success as ambassador was helping to solve the Trieste Crisis in 1953–1954. This was a border dispute between Italy and Yugoslavia that could have led to a war. She strongly supported the Italian government and influenced U.S. policy in the Mediterranean.

Luce believed that American aid was needed to prevent Italy from becoming communist. A study from 2016 showed that she secretly supported centrist Italian governments to weaken the Italian Communist Party.

She also threatened to boycott the 1955 Venice Film Festival if a certain American film was shown. Around this time, she became very ill from arsenic poisoning. Doctors found that the poisoning was caused by paint dust falling from her bedroom ceiling. This illness made her weak, and she resigned from her post in December 1956. When she left, an Italian newspaper said she showed "how well a woman can discharge a political post of grave responsibility."

In 1957, she received the Laetare Medal, a top award for American Catholics.

Nomination as Ambassador to Brazil

In 1959, President Eisenhower nominated Luce to be the US Ambassador to Brazil. She started learning Portuguese for the job. However, some Democratic senators opposed her appointment because of her strong conservative views. Even though she was confirmed by the Senate, her husband advised her to decline the job. Luce felt the controversy would make it hard for her to do her job well, so she never officially became ambassador to Brazil.

Later Political Life and Awards

After leaving office, Luce continued to be active in politics. She and her husband supported groups against communism. She also strongly supported Senator Barry Goldwater for president in 1964.

In 1973, President Richard Nixon appointed her to the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB). She served on this board until 1977 and was reappointed by President Reagan in 1981, serving until 1983.

In 1979, she was the first woman to receive the Sylvanus Thayer Award from the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Presidential Medal of Freedom

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan gave her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is one of the highest awards a civilian can receive in the United States. She was the first female member of Congress to get this award.

When giving her the medal, President Reagan praised her many achievements. He called her "A novelist, playwright, politician, diplomat, and advisor to Presidents." He said she had "served and enriched her country in many fields" and was a "persistent and effective advocate of freedom."

Clare Boothe Luce's Death

Clare Boothe Luce passed away from brain cancer on October 9, 1987, at the age of 84. She is buried in South Carolina at Mepkin Abbey, a place she and her husband once owned. Her grave is next to her mother, daughter, and husband.

Clare Boothe Luce's Legacy

Impact on Feminism

Later in her life, Clare Boothe Luce was seen as a hero for the feminist movement. She had mixed feelings about the role of women in society. She often advised women to marry and support their husbands. However, her own career showed how a woman from humble beginnings, without a college degree, could achieve great success as an editor, writer, playwright, reporter, politician, and diplomat.

Luce left a large part of her money to the Clare Boothe Luce Program. This program helps women enter science, mathematics, and engineering fields, which were traditionally dominated by men. Because of her strong will and refusal to let her gender stop her, Luce is seen as an important role model for many women. She never let her early poverty or lack of respect from men stop her from achieving more than many men around her. In 2017, she was honored by being added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

Clare Boothe Luce Program

Since 1989, the Clare Boothe Luce Program (CBLP) has provided a lot of private funding to support women in science, math, and engineering. All awards must be used in the United States. Students must be U.S. citizens, and faculty must be citizens or permanent residents. So far, the program has helped over 1,500 women.

The program has specific rules:

- At least half of the awards must go to Roman Catholic colleges, universities, and one high school (Villanova Preparatory School).

- Grants are only given to schools that offer four-year degrees, not directly to individuals.

The program has three main types of awards:

- Scholarships and research awards for undergraduate students.

- Fellowships for graduate and post-doctoral students.

- Support for professors at the assistant or associate level.

Influence on Conservatism

The Clare Boothe Luce Policy Institute (CBLPI) was started in 1993. This non-profit group works to help American women through conservative ideas, following Clare Boothe Luce's beliefs. The CBLPI brings conservative speakers to college campuses.

The Clare Boothe Luce Award, created in 1991, is the highest award from The Heritage Foundation for people who have made important contributions to the conservative movement. Famous people who have received this award include Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

See also

- List of notable brain tumor patients

- Women in the United States House of Representatives