Wendell Willkie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wendell Willkie

|

|

|---|---|

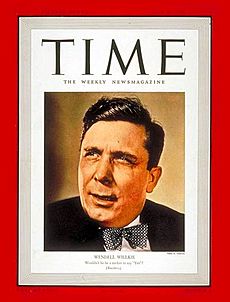

Willkie in 1940

|

|

| Born |

Lewis Wendell Willkie

February 18, 1892 Elwood, Indiana, U.S.

|

| Died | October 8, 1944 (aged 52) New York City, U.S.

|

| Resting place | East Hill Cemetery |

| Education | Indiana University, Bloomington (BA, LLB) |

| Political party | Democratic (before 1939) Republican (1939–1944) |

| Spouse(s) |

Edith Wilk

(m. 1918) |

| Children | Philip Willkie |

| Signature | |

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer and business leader. He became the Republican candidate for President in 1940.

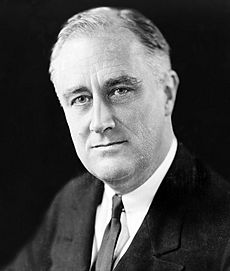

Willkie was known for supporting the Allies in World War II. Even though the U.S. was neutral before Pearl Harbor, he wanted America to help Britain and other countries fighting Nazi Germany. He ran against the current president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who won the election.

Willkie was born in Indiana in 1892. Both his parents were lawyers, and he followed in their footsteps. He served in World War I but did not see combat. After the war, he became a successful lawyer in Ohio. He later moved to New York City to work for a large electric company called Commonwealth & Southern Corporation (C&S). He quickly became its president in 1933.

President Roosevelt soon started the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). This government agency would provide power, competing with Willkie's company. From 1933 to 1939, Willkie fought against the TVA. He argued in Congress, in courts, and to the public. He eventually sold his company's property to the TVA for a good price. This made him well-known and respected.

Willkie had been a Democrat for a long time. But in 1939, he changed to the Republican Party. He did not run in the early primaries. Instead, he hoped to be chosen at the Republican convention if other candidates were stuck. As German forces advanced in Europe, many Republicans wanted a candidate who would help the Allies. They chose Willkie, who supported aid to Britain.

After losing the election, Willkie traveled overseas for President Roosevelt. He supported the president, which made some conservatives unhappy. Willkie ran for president again in 1944 but dropped out after losing a key primary election. He died in October 1944. Willkie is remembered for helping Roosevelt pass the Lend-Lease program. This program sent important supplies to the United Kingdom and other Allied nations.

Contents

Early Life and Education (1892–1919)

Lewis Wendell Willkie was born in Elwood, Indiana, on February 18, 1892. His parents, Henrietta and Herman Willkie, were both lawyers. His mother was one of the first women allowed to practice law in Indiana. His grandparents had come from Germany. They were involved in the 1848 revolutions there.

The Willkie family moved to Indiana because they were against slavery. Wendell was the fourth of six intelligent children. He learned to debate during family discussions at dinner. This skill helped him later in life.

Even though his first name was Lewis, everyone called him Wendell. His father was interested in politics. In 1896, he took his sons to see William Jennings Bryan, a Democratic presidential candidate. Bryan later stayed at their home, becoming Wendell's first political hero.

When Willkie was 14, his parents sent him to Culver Military Academy for the summer. They wanted him to be more disciplined. In high school, he became a good student, inspired by his English teacher. He joined the football team but preferred the debate team. He was class president in his final year.

During summer breaks, Willkie worked far from home. At 17, he worked in South Dakota and Yellowstone National Park. After high school, he went to Indiana University in Bloomington. He was a student rebel, reading Marx and asking for a course on socialism. He also helped manage a successful student campaign for Paul McNutt, who later became governor.

Willkie graduated in 1913. He taught high school history in Kansas to earn money for law school. In 1914, he worked as a lab assistant in Puerto Rico. Seeing workers suffer there made him care more about social justice.

He enrolled at Indiana School of Law in 1915. He was a top student and graduated with high honors in 1916. He joined his parents' law firm. On April 2, 1917, he volunteered for the United States Army. This was the day President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. An army clerk mixed up his first two names, so he became Wendell Lewis Willkie. He was sent for artillery training. He arrived in France as the war ended and did not fight.

In January 1918, he married Edith Wilk. They had one son, Philip. Willkie was discharged from the army in early 1919.

Lawyer and Business Leader (1919–1939)

Akron Attorney and Activist

After the army, Willkie returned to Indiana. He thought about running for Congress. But he was told his chances would be better in a city. In May 1919, he got a job with the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio. He soon left to join a law firm.

Willkie became active in the Akron Democratic Party. He was a delegate to the 1924 Democratic National Convention. He fought against the Ku Klux Klan, which was powerful at the time. In 1925, he helped remove Klan members from the Akron school board.

His law firm represented several public utility companies. Willkie became known for handling utility cases. In 1925, he became president of the Akron Bar Association. The chairman of Commonwealth & Southern Corporation (C&S), B.C. Cobb, noticed Willkie. In 1929, Cobb offered Willkie a job as corporate counsel for C&S. Willkie accepted and moved to New York City.

Leading Commonwealth & Southern

Wendell and Edith Willkie moved to New York in October 1929. This was just weeks before the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Willkie quickly grew to love the city. He went to Broadway theatre and read many newspapers. He became friends with Irita Van Doren, a book review editor. She introduced him to new ideas and friends.

At C&S, Willkie quickly moved up. He impressed his bosses. Most of his work was outside New York City. Cobb, a leader in the electricity business, had combined 165 utility companies to make C&S the largest in the country. In January 1933, Willkie became president of C&S.

Willkie stayed interested in politics. He was a delegate to the 1932 Democratic National Convention. He supported Newton D. Baker for president. But Franklin D. Roosevelt won the nomination. Willkie was disappointed but supported Roosevelt. He even donated money to his campaign.

The TVA Battle

Soon after becoming president, Roosevelt proposed creating the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). This government agency would bring flood control and cheap electricity to the poor Tennessee Valley. But the TVA would compete with private power companies like C&S. Willkie spoke to Congress in April 1933. He liked the idea of developing the Tennessee Valley. But he thought the government should only sell power from dams, not compete directly.

C&S and the TVA negotiated for months. They reached an agreement in January 1934. C&S agreed to sell some of its properties in the Tennessee Valley. The government agreed that the TVA would not compete in many areas. Willkie became the main spokesperson for the private electric power industry.

Willkie and Roosevelt met for the first time in December 1934. The meeting seemed friendly. But each man told a different story about it. Roosevelt decided that utility holding companies needed to be broken up. He told Willkie this in January 1935. Meanwhile, the private companies tried to stop the TVA. They spread false information and built "spite lines" to claim areas.

Through 1935, Willkie was the industry's main lobbyist. When the Senate passed a bill to break up the companies, Willkie gave speeches. He asked the public to oppose the law. Many letters were sent to congressmen. But it was found that many were paid for by the electric companies. Roosevelt then pushed Congress to pass a law requiring the breakup within three years.

In September 1936, Roosevelt and Willkie met again. Willkie voted for the Republican candidate, Alf Landon, in the election. But Roosevelt won by a huge amount. In December, a court stopped the TVA. Willkie then took his case to the public. He wrote articles and gave speeches. He said that government policies against utilities were hurting the economy. The Saturday Evening Post called Willkie "the man who talked back".

Willkie and David Lilienthal, the head of TVA, negotiated for a year. Willkie wanted $88 million for C&S properties. The TVA offered $55 million. After a final court loss for C&S in January 1939, they reached a deal. C&S sold its assets to the TVA for $78.6 million. Willkie was seen as a tough negotiator. He gained national attention and was even considered a possible presidential candidate for 1940.

1940 Presidential Election

Becoming a Candidate

The 1940 presidential campaign happened during World War II in Europe. The U.S. was neutral. But the country was divided. Some people, called isolationists, wanted to stay out of the war. Others, called interventionists, felt America should help the Allies fight Nazi Germany. The main Republican candidates were mostly isolationists.

Willkie was talked about as a possible Democratic candidate as early as 1937. He gained more attention after a radio debate in January 1938. He appeared as a caring businessman. Positive news stories about Willkie continued. In July 1939, he was on the cover of Time magazine. Willkie initially didn't think he would run for president. But he changed his mind. His friend, Russell Davenport, became his campaign manager. Willkie wrote an article urging both parties to support business and oppose foreign aggression.

Willkie believed Roosevelt would run for a third term. So, he decided to run as a Republican. In late 1939, he changed his party registration. He said Roosevelt's policies were anti-business. He felt his old party no longer represented his values. He later said, "I did not leave my party. My party left me."

The war in Europe started in September 1939. Most Americans wanted to stay out of it. But Willkie often spoke about the danger to America. He said the U.S. needed to help Britain and the Allies.

Willkie did not enter the Republican primary elections. He hoped to be chosen at the convention if no other candidate won enough votes. His campaign was run by many political newcomers. Groups called "Willkie Clubs" formed. They attracted Republicans who wanted a new leader to beat Roosevelt. Willkie appealed to liberal Republicans. His casual look and Indiana accent made him seem like an ordinary person.

As the convention approached in June, Hitler's forces advanced in Europe. Delegates worried about choosing an isolationist. Willkie, who spoke against isolationism and was a successful business leader, became an attractive option. Willkie gave many speeches. He gained support from important governors like Harold Stassen and Leverett Saltonstall. Polls showed his support growing quickly.

The Convention

The 1940 Republican National Convention began in Philadelphia on June 24, 1940. Delegates discussed the war and the candidates. Roosevelt had just appointed two Republicans who supported intervention to his cabinet. This divided Republicans.

Willkie arrived in Philadelphia two days before the convention. He walked from the train station to his hotel, answering questions. His campaign was run from secret rooms. His supporters sent many telegrams to delegates. Key convention officials supported Willkie. This included House Minority Leader Joe Martin.

On the first night, Governor Stassen gave a speech. He then announced his support for Willkie. The next night, former President Herbert Hoover spoke. But his speech was hard to hear. The Dewey campaign tried to stop Willkie's growing support. Willkie met with delegates and reporters. He even met with African American delegates.

Indiana Congressman Charles Halleck gave the speech nominating Willkie. He said Willkie's recent change to the Republican Party was not a problem. When Halleck said Willkie's name, some delegates booed. But people in the public balconies cheered loudly, chanting, "We want Willkie!" Willkie supporters had been given many tickets to the galleries.

On the first vote, Thomas E. Dewey had the most votes. But on the second vote, Dewey started to lose support. The race became between Robert A. Taft and Willkie. Willkie listened from his hotel room. He refused to make deals to get votes. On the sixth vote, Willkie took the lead. Other candidates released their delegates, and many went to Willkie. Willkie became the Republican nominee for president.

Willkie chose Senator Charles McNary of Oregon as his running mate. McNary was a lawyer and farmer. He was popular in the West. Willkie became the first Republican nominee to speak to the convention after being chosen. He said, "Democracy and our way of life is facing the most crucial test it has ever faced... we here are not Republicans, alone, but Americans, to dedicate ourselves to the democratic way of life."

The General Election Campaign

After the convention, Willkie returned to New York. He resigned from C&S. Polls showed him only six points behind Roosevelt. Roosevelt was nominated by the Democrats in July. He said he would not actively campaign because of the world crisis.

Willkie formally accepted the nomination in Elwood, Indiana, on August 17. A huge crowd of at least 150,000 people attended. It was a very hot day. Willkie struggled to read his speech. He stayed in Rushville, Indiana, for the next month. He wanted to be seen as connected to his home state, not Wall Street. He supported Roosevelt's aid to the Allies. He also backed a peacetime draft.

Conservatives and isolationists were not very excited about Willkie. Roosevelt did not mention Willkie by name. He wanted to avoid giving him publicity. This made Willkie's campaign harder. Willkie promised to keep New Deal social programs. He also promised to expand Social Security and provide jobs for everyone. He said, "I pledge a new world."

On September 12, Willkie began a train tour. He visited 31 states. He attracted large crowds in many places. But reporters saw few working-class people at his rallies. Some people in working-class areas booed him. Willkie's wife, Edith, traveled with him. She did not like the media attention.

As the election got closer, polls showed Roosevelt far ahead. Willkie started to say that Roosevelt would lead the U.S. into war. He argued that he would keep America out of war. This new approach helped him in the polls. Roosevelt responded by giving speeches. He said, "Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign war."

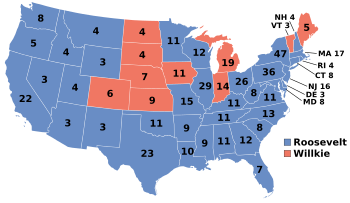

Willkie ended his campaign on November 2 with a rally in New York. Polls showed him four points behind. Many experts thought it would be a close race. On Election Day, November 5, 1940, Roosevelt won a third term. He received 55 percent of the popular vote. Willkie won 10 states, while Roosevelt won 38. Willkie's 22.3 million votes set a record for a Republican candidate at that time.

After the election, Willkie gave a radio speech. He urged his supporters to back Roosevelt when it was important for the country. Roosevelt later said, "I'm happy I've won, but I'm sorry Wendell lost."

Activist and Statesman (1940–1943)

Visit to the United Kingdom

Even though he lost, Willkie became an important public figure. He decided his next goal was to help Britain with military aid. On January 13, 1941, he announced his support for the president's Lend-Lease program. This program was very unpopular with Republicans. Willkie's support caused a big stir.

Roosevelt saw Willkie's talents. He wanted to use his former opponent's influence. Roosevelt's advisor suggested Willkie travel to Britain. This would show that both parties supported Britain. Willkie was already planning a visit. Roosevelt believed Willkie's visit would be more effective than sending one of his own advisors.

Willkie visited Roosevelt at the White House on January 19, 1941. Roosevelt asked Willkie to be his informal representative to Britain. Willkie accepted. Roosevelt gave him a letter for British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Traveling abroad was not common for politicians then. So, Willkie's mission got a lot of public attention. He left for London on January 22.

In London, Willkie told the press he wanted to help the U.S. give Britain "the utmost aid possible." He saw the damage from Nazi bombing in British cities. He walked the streets during the Blitz, visiting bomb shelters. Churchill hosted Willkie and had "a long talk with this most able and forceful man."

Willkie's visit to Britain was a success. He also went to Ireland to try to persuade them to join the Allies, but he was unsuccessful. Willkie returned to Washington on February 5. He testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on February 11. His support was key to passing Lend-Lease.

Willkie's testimony made him a leading supporter of intervention outside the government. Roosevelt publicly backed Willkie in a radio address. A Gallup poll in March 1941 showed that 60 percent of Americans thought Willkie would have been a good president.

In April 1941, Willkie joined a New York law firm. Two months later, he represented movie producers. They were accused of making pro-war propaganda. Willkie defended their right to free speech. Congress did not take further action.

In late 1941, Willkie fought to repeal the Neutrality Act. He argued that the aviator Charles Lindbergh's speech blaming American Jews for the war was "un-American." Willkie urged Republican congressmen to repeal the act. The measure passed with some Republican votes. Roosevelt wanted Willkie to join his administration. But Willkie wanted to remain independent.

Wartime Advocate

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Willkie fully supported Roosevelt. In July 1942, Willkie suggested another foreign mission to Roosevelt. The following month, Willkie announced he would visit the Soviet Union, China, and the Middle East.

Willkie's mission was to represent Roosevelt. He would show American unity, gather information, and discuss postwar plans. He left the U.S. on August 26. His first stop was North Africa, where he met General Montgomery. In Beirut, he stayed with General de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French. In Jerusalem, Willkie met with Jews and Arabs. He said both peoples should be part of the government.

In the Soviet Union, he met with Stalin. When he returned, he argued for more generous Lend-Lease terms for the USSR. In China, Willkie was hosted by Chiang Kai-shek and Madame Chiang. He visited the front lines to see Chinese forces fighting the Japanese. He spoke out against colonialism. His statements made Churchill angry, who said, "We mean to hold our own."

On October 26, 1942, Willkie gave a "Report to the People" on the radio. About 36 million people listened. The following April, he published One World. This book described his travels. It urged America to join a global organization after the war. The book was a huge bestseller. It sold a million copies in its first month. It was very influential because Willkie was seen as being above party politics.

Civil Rights Activism

During his 1940 campaign, Willkie promised to end racial segregation in Washington, D.C. He also pledged to integrate the civil service and armed forces. He gained support from the two largest African American newspapers. Roosevelt feared losing black voters. So, he made several important promotions for African Americans. Roosevelt succeeded in keeping most of the black vote. After the election, Willkie promised to keep fighting for civil rights.

Willkie told Republicans they needed to fully support equal rights for minorities. He criticized Roosevelt for giving in to Southern racists. In 1942, Willkie spoke at a convention for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He urged the integration of the armed forces. When a violent race riot happened in Detroit in June 1943, he spoke on national radio. He criticized both parties for ignoring racial issues.

In 1943, Willkie worked with Walter White, the executive secretary of the NAACP. They tried to convince Hollywood to show black people in better roles in films. Movie leaders promised changes. But after Willkie's death in 1944, they went back to showing black people in stereotypical roles. The NAACP later named its headquarters the Wendell Willkie Memorial Building.

On November 9, 1942, Willkie argued a case before the Supreme Court. He represented William Schneiderman, a Communist Party secretary. The government had taken away Schneiderman's citizenship. Willkie argued that Schneiderman's rights should be defended. He said, "Of all the times when civil liberties should be defended, it is now." In 1943, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Schneiderman. Willkie also spoke out against blaming Jews for the war. He warned against "witch-hanging and mob-baiting." He received the American Hebrew Medal for 1942.

1944 Presidential Campaign and Death

Willkie spent much of 1943 preparing to run for president again. He spoke to Republican and nonpartisan groups. He did not meet with Roosevelt. Republican leaders wanted him to campaign for the party in the 1942 elections. But he went on his world trip instead. The publicity he received as Roosevelt's envoy frustrated many Republicans. By 1943, few Republican members of Congress supported Willkie.

Willkie announced his candidacy in an interview in October 1943. He said returning to isolationism would be bad for the party. He decided to enter several primary elections to show his public support. He chose Wisconsin for his first major test. Willkie had not won Wisconsin in 1940. His advisors worried about the large German-American population there, who were mostly isolationist. Willkie said if he did badly in Wisconsin, he would end his campaign.

Willkie won the New Hampshire primary on March 14, taking six out of eleven delegates. This was seen as a disappointment. In Wisconsin, Willkie campaigned for two weeks. He was supported by most newspapers. But polls showed him far behind Thomas E. Dewey.

On March 16, Willkie gave eight speeches. The fast pace hurt his voice. He traveled through a blizzard to reach a rally. He attracted large crowds. He told them the Republican party needed to accept the New Deal. He also said the U.S. must stay active in the world after the war. On April 4, Dewey won 17 of Wisconsin's 24 delegates. Willkie's delegates finished last. The next night, Willkie announced he was ending his campaign. He said, "It is obvious now that I cannot be nominated."

Final Months and Death

After losing his second presidential bid, Willkie said he would return to practicing law. But his friends doubted he would be happy there. Roosevelt considered asking Willkie to be his running mate for a fourth term. But Willkie was hesitant. Willkie and Roosevelt discussed forming a new liberal political party after the war. But Willkie stopped contact with the White House after leaks to the press. He felt Roosevelt had used him for political gain.

Willkie was not invited to speak at the 1944 Republican National Convention. He declined a pass as an "honored guest." Dewey hoped to get Willkie's support. But Willkie refused to endorse him before he died. Willkie wrote articles for Collier's magazine. One urged an international foreign policy. The other demanded civil rights for African Americans.

Willkie had not taken good care of his health. He smoked a lot and rarely exercised. In August 1944, he felt weak while traveling to his home in Rushville. He had a heart attack. But he refused to go to a hospital.

Willkie's condition worsened. In mid-September, he had another heart attack on a train to New York. He was in great pain when he arrived. He was taken to Lenox Hill Hospital. He seemed to recover a bit. He worked on his second book, An American Program. On October 4, he got a throat infection. On October 7, he had three more heart attacks. The hospital announced his condition was critical. The next morning, Willkie had one last heart attack, which was fatal. He had suffered over a dozen heart attacks in the hospital.

Roosevelt praised Willkie's "tremendous courage." He said Willkie "contributed to saving freedom at a moment of great peril." War Secretary Henry L. Stimson offered to have Willkie buried in Arlington National Cemetery. But Edith Willkie wanted him buried in his home state, Indiana. His casket was placed in a church in New York. 60,000 people came to see it. Wendell and Edith Willkie are buried together in Rushville's East Hill Cemetery. Their gravesite has a cross and a stone book with quotes from One World.

Willkie's 1940 running mate, McNary, died eight months before him. This was the only time both members of a major-party presidential ticket died during the term they sought election.

Legacy and Remembrance

After the 1940 convention, Roosevelt called Willkie's nomination a "Godsend to our country." This was because it ensured the election would not be about aid to Britain. Historian Walter Lippmann believed Willkie's nomination was vital for Britain's survival. He said it made it possible to unite the free world when Britain was almost defeated. Charles Peters wrote that Willkie's impact on the U.S. and the world was "greater than that of most men who actually held the office [of president]." He said Willkie "stood for the right things at the right time."

Willkie's nomination left a lasting mark on the Republican Party. Conservatives were unhappy with the success of the more liberal wing. Gerald R. Ford, who worked on Willkie's campaign, later wrote that his participation "made a lot of difference to me."

Willkie's trip around the world and his book One World increased public support. Many Americans believed the U.S. should stay active internationally after the war. Indiana University president Herman B Wells said One World had a "profound influence on the thinking of Americans."

However, Willkie's support for internationalism cost him standing in the Republican Party. He was seen as too liberal.

The World War II Liberty Ship SS Wendell L. Willkie was named in his honor.

In 1965, Indiana University built Willkie Quadrangle. This is an 11-story student residence hall named after him.

In 1992, the United States Postal Service released a 75-cent stamp to mark 100 years since Willkie's birth. Willkie's biographer, Steve Neal, wrote that Willkie "had won something much more important, a lasting place in American history." Willkie once said he would rather be remembered as someone who "contributed to saving freedom at a moment of great peril" than an "unimportant President."

Works

- One World (1943)

- An American Program, Simon and Schuster, 1944 (a collection of short essays)

See also

In Spanish: Wendell Willkie para niños

In Spanish: Wendell Willkie para niños

- State of the Union, a play believed to be based on Willkie's presidential run.

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |