German revolutions of 1848–1849 facts for kids

Quick facts for kids German Revolutions of 1848–1849 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Revolutions of 1848 and the unification of Germany | |||||||

The Flag of Germany's colors come from this time: Revolutionaries cheering in Berlin on March 19, 1848, with the Berlin Palace in the background. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

German revolutionaries |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| No single leader | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| ~45,000 German Federal Army | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Many thousands of peasants and workers | |||||||

The German Revolutions of 1848–1849 were a series of protests and rebellions in the German states. They happened at the same time as many other revolutions across Europe. People in the German lands were unhappy with how things were run. At the time, Germany was not one country. It was a group of 39 independent states called the German Confederation. These states were mostly ruled by leaders who had almost all the power.

The revolutions started in March 1848. Because of this, they are sometimes called the March Revolution (German: Märzrevolution). People wanted more freedom and a say in the government. Many also hoped for a united Germany. This idea was called pan-Germanism. Middle-class people wanted "liberal" changes. This meant things like freedom of speech and a government that represented the people. Working-class people wanted better living and working conditions.

However, the middle class and working class had different goals. This made it easier for the old rulers to stop the revolution. Many liberals had to leave Germany to avoid punishment. These people became known as Forty-Eighters. A lot of them moved to the United States.

Contents

- What Caused the Revolutions?

- Austria's Role in the Uprisings

- Baden's Fight for Change

- The Palatinate Uprising

- Prussia and the Berlin Protests

- Saxony's May Uprising

- The Rhineland Revolts

- Bavaria and King Ludwig I

- Liechtenstein's Peaceful Changes

- The Frankfurt National Assembly

- Prussia Regains Control

- Why Did the Revolution Fail?

- Success for the Peasants

- Images for kids

- See also

What Caused the Revolutions?

The unhappiness that led to the 1848 revolutions started years earlier. In 1832, people protested at the Hambacher Fest. They were against high taxes and government control over what could be said or written. This control was called censorship. This festival was important because people started using the black-red-gold colors. These colors became a symbol of a united, free Germany. Today, these are the colors of the German flag.

People in many German states wanted more freedom and rights. They were inspired by big protests in Paris, France, in February 1848. These French protests made their king, Louis-Philippe of France, give up his throne.

News of the French revolution spread quickly. Soon, people in Austria and Germany also started protesting. On March 13, 1848, large protests happened in Vienna, the capital of Austria. This led to Prince von Metternich, a very powerful Austrian leader, resigning. He then left the country. Because these Vienna protests happened in March, the revolutions in Germany are often called the March Revolution.

Some German rulers were scared they would lose their power. So, they agreed to some of the protesters' demands, at least for a while. People held large meetings and marches, asking for:

- Freedom to write and publish news freely (called Freedom of the press)

- Freedom to meet in groups (called Freedom of assembly)

- Written constitutions (a set of basic laws for the country)

- The right for people to have weapons

- A Parliament (a group of people elected to make laws)

Austria's Role in the Uprisings

In 1848, Austria was the most powerful German state. It was the head of the German Confederation. Klemens von Metternich, the Austrian chancellor, had been in charge of Austrian politics for many years.

On March 13, 1848, university students in Vienna held a big street protest. They wanted a constitution and a government chosen by all men. Emperor Ferdinand and Metternich ordered soldiers to stop the protest. Soldiers fired at the students, and some were killed. This made the working-class people of Vienna join the students. The protest turned into an armed uprising.

The government of Lower Austria demanded Metternich resign. Emperor Ferdinand agreed, and Metternich left for London. Ferdinand then appointed new ministers who seemed more liberal. They wrote a constitution in April 1848. However, many people didn't like it because most of them were not allowed to vote. So, people in Vienna protested again in May, building barricades in the streets. Emperor Ferdinand and his family fled the city.

Ferdinand later made some promises to the people. He agreed to turn the Imperial Diet (a kind of parliament) into a group that would be elected by the people. This group would write a new constitution. He returned to Vienna in August 1848. But soon, there were more protests about unemployment and low wages. Austrian troops fired on these protesters too.

In September 1848, Emperor Ferdinand sent troops to Hungary. He wanted to stop a democratic rebellion there. When these troops were defeated, people in Vienna protested against the Emperor's actions. This was called the Vienna Uprising. Emperor Ferdinand fled Vienna again. In December 1848, he gave up the throne to his nephew, Franz Joseph.

Baden's Fight for Change

The Grand Duchy of Baden was one of the first German states to see protests. This happened even though it was already quite liberal. After news of the February revolution in Paris arrived, peasants in Baden started to burn mansions of nobles.

On February 27, 1848, people in Mannheim demanded a list of rights. Similar demands were made in other German states. Rulers were surprised by how strong the protests were. They quickly agreed to many of the "demands of March."

The revolution in Vienna encouraged more protests across Germany. People wanted an elected government and a united Germany. The rulers agreed to a temporary parliament. This parliament met in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt am Main. Its job was to write a new constitution. Most of the members of this parliament wanted Germany to have a king but also a constitution.

Baden sent two democrats, Friedrich Karl Franz Hecker and Gustav von Struve, to this parliament. But they got frustrated with the slow progress and walked out. This and other protests pushed the parliament to call for an All-German National Assembly to be formed. This new National Assembly was chosen, and it met in Frankfurt in May 1848.

However, republican troublemakers continued to cause unrest in Baden. The Baden government tried to stop them by arresting Joseph Fickler, a leader of the Baden democrats. This led to more protests and a full uprising in April 1848. This was known as the Hecker Uprising. But Bavarian and Prussian troops defeated the revolutionaries. In May 1849, revolutionary activity started again in Baden.

The Palatinate Uprising

In the spring of 1849, revolutions flared up again. They started in Elberfeld in the Rhineland and quickly spread to Baden and the Palatinate. The Palatinate was part of Bavaria at the time. The uprisings in Baden and the Palatinate were closely linked.

In May 1849, the Grand Duke of Baden had to leave his capital, Karlsruhe. He asked Prussia for help. Temporary governments were set up in both the Palatinate and Baden. In Baden, the public and the army supported the changes. The army wanted a constitution, and the state had money and weapons. The Palatinate was different.

The Palatinate had more wealthy citizens who were against the revolutionary changes. The army there did not support the revolution. There were not enough supplies. When the new government took over in the Palatinate, they found little money and few weapons. They tried to buy arms from France and Belgium but failed.

The temporary government in the Palatinate had several leaders. These included Ludwik Mieroslawski, who was put in charge of the armed forces. Many people, including Frederick Engels (a friend of Karl Marx), joined the fight in Baden and the Palatinate. They believed they were fighting for the rights of all Germans.

However, the leaders in Baden and the Palatinate did not work well together. Mieroslawski lost key battles and had to retreat with his troops to Switzerland. The uprising was eventually crushed by Prussian and Bavarian forces. This marked the end of the revolutionary uprisings that had started in 1848.

Prussia and the Berlin Protests

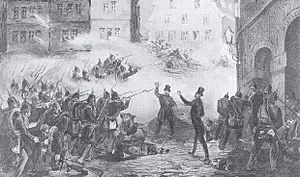

In Berlin, the capital of Prussia, big protests also took place. On March 13, 1848, soldiers attacked a group of people, killing one and injuring many. On March 18, a huge demonstration happened. When soldiers fired shots, people built barricades in the streets. A fierce battle lasted for 13 hours until the soldiers were ordered to pull back. Hundreds of people died.

King Frederick William IV was shocked. He promised to reorganize his government. He also promised to allow elections, create a constitution, and grant freedom of the press. He also said that "Prussia was to be merged forthwith into Germany." This meant Prussia would become part of a united Germany.

The next day, the King walked through Berlin to attend a funeral for those killed in the uprising. He and his ministers wore the revolutionary colors of black, red, and gold. Polish prisoners, who had been jailed for planning a rebellion, were freed and cheered by the people.

In May 1848, an elected assembly met in Berlin to write a constitution for Prussia. However, by November, the King felt more powerful again. He sent the assembly away from Berlin and later introduced his own constitution. This constitution kept most of the power in his hands.

Saxony's May Uprising

In Dresden, the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony, people protested in the streets. They asked their King, Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, for changes to the voting system. They also wanted more social fairness and a constitution.

The famous German composer Richard Wagner was very involved in the revolution in Dresden. He supported the idea of a democratic republic. During the May Uprising in Dresden in May 1849, he helped the temporary government. About 2,500 people fought on the barricades. When the uprising failed, Wagner had to flee to Switzerland to avoid arrest.

Saxony had been a constitutional monarchy (a kingdom with a set of rules) since 1830. The 1848 Revolution brought more reforms to its government. Many people from Saxony later moved to the United States, especially to Texas. There, they formed a German Texan community.

The Rhineland Revolts

The Rhineland region had been under French control during Napoleon's time. This had brought changes that ended the old feudal system. In this system, nobles and clergy had all the power. The Rhineland became an important industrial area. By 1848, cities like Aachen, Cologne, and Düsseldorf had many factories and a large working class. These workers were politically active.

Prussia controlled the Rhineland at this time. The Prussian government treated the Rhinelanders poorly. They tried to bring back old, unfair systems. So, many people in the Rhineland were strongly against Prussian rule.

When King Frederick William IV of Prussia promised reforms in March 1848, people in the Rhineland were hopeful. They did not join the early uprisings. But in the spring of 1849, the Prussian government called up many men for the army reserve, called the Landwehr. People believed this was illegal because it was peacetime. The King also got rid of a parliament that had passed an unpopular constitution. This made everyone in the Rhineland – workers, middle class, and wealthy citizens – rise up. They wanted to protect the reforms they thought they were losing.

In May 1849, uprisings happened in several Rhineland towns like Elberfeld and Düsseldorf. In Elberfeld, 15,000 workers built barricades and fought Prussian troops. They formed a Committee of Public Safety to lead the revolt. However, the committee members couldn't agree on a plan. The wealthy citizens got scared of the armed workers and pulled their support. The uprising was eventually crushed.

Bavaria and King Ludwig I

In Bavaria, King Ludwig I was unpopular. This was because of his relationship with Lola Montez, a dancer. The nobles and the Church did not approve of her. When she tried to make liberal changes with a Protestant prime minister, Catholic conservatives protested on February 9, 1848. This was one of the first demonstrations of that year.

Liberal students used this situation to demand political changes. Students all over Bavaria started protesting for a new constitution. King Ludwig I made a few small reforms, but it wasn't enough. On March 16, 1848, he gave up the throne to his son, Maximilian II. Some reforms were made, but the government soon regained full control.

Liechtenstein's Peaceful Changes

Inspired by revolutions elsewhere, people in Liechtenstein also demonstrated. They were against the absolute rule of Prince Aloys II. They wanted better economic and political conditions. On March 22, 1848, a committee was formed to lead the movement. This committee included Peter Kaiser. They managed to keep things peaceful.

A council was elected to draft a new constitution for Liechtenstein. For a short time, Liechtenstein had its first democratic representation. However, after the German revolutions failed, Prince Aloys II took back absolute power in 1852.

The Frankfurt National Assembly

On March 6, 1848, German liberals in Heidelberg planned elections for a German national assembly. This temporary Parliament met on March 31 in St. Paul's Church in Frankfurt. They called for free elections for an assembly for all of Germany, and the German states agreed.

On May 18, 1848, the National Assembly opened in St. Paul's Church. Many of its 586 members were professors or teachers. Because of this, it was called the "professors' parliament" (German: Professorenparlament).

The Assembly, led by Heinrich von Gagern, aimed to create a modern constitution for a united Germany. But they faced big problems from the start:

- Regionalism: Local issues were often seen as more important than uniting Germany.

- Austro-Prussian conflicts: Austria and Prussia were rivals and disagreed on many things.

Archduke John of Austria was chosen as a temporary head of state. But this new government didn't have much power. Most states didn't fully support it. The Assembly lost public trust when Prussia acted on its own in a dispute over Schleswig-Holstein (regions near Denmark). It also lost trust when Austria used its army to stop an uprising in Vienna.

Key Questions for the New Germany

The Assembly debated important questions about Germany's future:

- Greater Germany vs. Smaller Germany: Should the new Germany include the German-speaking parts of Austria? Or should it exclude Austria, with Prussia taking the lead? This was decided when Austria created a new constitution for its entire empire. This meant a "Greater Germany" was no longer possible.

- Type of Government: Should Germany be a monarchy with a king whose children would inherit the throne? Should it have an elected monarch? Or should it be a republic (a country without a king)?

- Power Distribution: Should Germany be a federation of fairly independent states, or should it have a strong central government?

In December 1848, the Assembly announced the "Basic Rights for the German People." This said all citizens were equal before the law. On March 28, 1849, they finally passed a draft constitution. The new Germany was to be a constitutional monarchy (a kingdom with a constitution). The King of Prussia was to be the "Emperor of the Germans." This was approved by a small majority. Twenty-nine smaller states accepted this constitution. However, major states like Austria, Prussia, Bavaria, Hanover, and Saxony did not.

Prussia Regains Control

By late 1848, the Prussian nobles and generals had taken back power in Berlin. They had only retreated temporarily after the March protests. General von Wrangel led troops to recapture Berlin for the old rulers. King Frederick William IV of Prussia quickly sided with them again. In November, the king dismissed the Prussian National Assembly. He then introduced his own constitution, which kept most of the power for himself. This constitution allowed all men to vote. But it used a three-class system. This system gave more power to those who paid more taxes. So, over 80% of voters controlled only one-third of the seats in the lower house of parliament.

On April 2, 1849, members of the Frankfurt National Assembly met with King Frederick William IV in Berlin. They offered him the crown of Emperor under their new constitution. The King said he was honored. But he said he could only accept the crown if other monarchs and free cities agreed. However, in a private letter, he wrote that he felt insulted. He said he was offered a crown "from the gutter," dirtied by revolution.

Austria and Prussia then pulled their representatives from the Frankfurt Assembly. The remaining radical members moved to Stuttgart. But this "rump parliament" was soon broken up by troops from Württemberg. Armed uprisings in support of the constitution in Saxony, the Palatinate, and Baden were quickly crushed by local armies. Prussian troops helped them. Leaders and participants were executed or given long prison sentences if caught.

The achievements of the March 1848 revolutionaries were undone in all German states. By 1851, the Basic Rights had also been abolished almost everywhere.

Why Did the Revolution Fail?

The Revolution of 1848 did not succeed in uniting the German-speaking states for several reasons:

- Divisions in the Frankfurt Assembly: The members had many different ideas and interests. Moderate liberals wanted to write a constitution and present it to the kings and princes. Radical members wanted the Assembly to declare itself the new government. They couldn't agree on these basic goals.

- Lack of Power: The Frankfurt Assembly had no power to collect taxes or create an army. It depended on the goodwill of the monarchs. The monarchs were not eager to give up their power.

- Caution of Liberals: Many moderate liberals were afraid of losing their jobs or causing too much chaos. They preferred to negotiate with the rulers rather than push for radical changes.

- Weakness of the Left: The radical groups failed to get enough support from ordinary people for a large-scale uprising.

- Strength of Monarchs: The rulers of the German states gradually realized they were not in serious danger. They had strong armies and were not willing to give up their power to a united Germany. Prussia, the strongest military power, had its own plans and did not fully support the Assembly.

The Frankfurt Assembly did manage to start the Reichsflotte, the German Navy, on June 14, 1848. This was important for Germany's future.

However, the Assembly's weakness was clear in how it handled a conflict with Denmark. This was over the regions of Schleswig and Holstein. Prussia made a peace treaty with Denmark without the Assembly's approval. When the Assembly later approved this treaty, it lost a lot of public support.

Many disappointed German patriots, like Carl Schurz and Franz Sigel, moved to the United States. They became known as the Forty-Eighters.

Success for the Peasants

Even though the revolution failed to unite Germany or create a lasting democratic government, it had one major success. Before 1848, most people in the German Confederation and the Austrian Empire were peasants. Many of them lived under a system called serfdom. This meant they were not free and had to work for landowners.

The peasant revolts during 1848–1849 were very large. They succeeded in ending serfdom and forced labor across the German Confederation, the Austrian Empire, and Prussia. Hans Kudlich was a key leader in this movement. He is remembered as the "liberator of peasants."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Revolución alemana de 1848-1849 para niños

In Spanish: Revolución alemana de 1848-1849 para niños