Germans in the American Revolution facts for kids

During the American Revolution, people of German heritage played important roles on both sides of the conflict. Many small German states in Europe supported the British. This was partly because King George III of Britain was also the ruler of the German state of Hanover. About 30,000 German soldiers fought for the British, making up about a quarter of their land forces. Among these, about 12,000 were Hessian soldiers, who served as helpers for the British.

However, many Germans living in America, known as German Americans, supported the American cause. Most of them lived in Pennsylvania and upstate New York. While some religious groups, like the Amish, remained neutral, the majority of German Americans sided with the Patriots. After the war, it's believed that nearly 5,000 of the German soldiers who fought for the British decided to stay and live in the United States.

German Soldiers Who Fought for Britain

In Europe, Germany was not one country but many separate states. Some of these states had worked with Britain before. They were willing to help Britain during the American Revolution. Britain had often used soldiers from other countries in its wars. However, using these soldiers against people who were once British subjects was a new and debated idea. Despite some disagreement, the British Parliament approved sending German soldiers to quickly stop the rebellion.

Some Europeans also debated the practice of "renting" soldiers to another country. But the people in these German states were often proud of their soldiers serving abroad. Interestingly, Prussia refused to send its soldiers to help Britain. Germans living in America did not join these rented units. However, some did join regular British army units.

Britain needed thousands of these soldiers quickly. They had to meet certain standards, like a minimum height and enough teeth to use a flintlock musket. Recruiters sometimes had to pay if soldiers deserted or lost equipment. In total, about 40,000 German soldiers were sent to different places, including North America. In North America, these German units made up more than a third of the British forces.

Americans were very concerned when these hired German fighters arrived. Many American leaders said they would declare independence if King George used such soldiers against them. The Patriots called these hired German troops "mercenaries." This anger was even written into the United States Declaration of Independence, which said the King was "transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries."

It's important to understand the difference between "auxiliaries" and "mercenaries." Auxiliaries are soldiers who serve their own ruler but are sent to help another ruler. Mercenaries are individuals who fight for a foreign ruler for money. By this definition, the German troops in the American Revolution were auxiliaries, not mercenaries. However, early American historians often used the term "mercenaries" to show a clear difference between these foreign, professional armies and the American citizen-soldiers fighting for freedom.

Throughout the war, the United States tried to convince these German soldiers to stop fighting. In 1778, the American Congress offered them land and farm animals if they switched sides. After the war, Congress also offered free farmland to encourage these Germans to stay in the United States. Britain also offered land and tax benefits to its Loyalist soldiers who wanted to settle in Nova Scotia in present-day Canada.

Hesse-Kassel's Soldiers

The state of Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel was one of the main suppliers of soldiers to Britain. This state often rented out its professional armies to other countries to help its economy. This allowed Hesse-Kassel to have a larger army and play a bigger role in European politics. About 7% of its population was in military service. The Hessian army was very well-trained and equipped. Its soldiers fought bravely for whoever paid their ruler.

Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, who was King George III's uncle, initially sent over 12,000 soldiers to America. These Hessian soldiers faced challenges getting used to North America. Many became ill, which delayed an attack on Long Island. From 1776 onwards, Hessian soldiers joined the British Army in North America. They fought in most major battles, including those in New York and New Jersey campaign, the Battle of Germantown, the Siege of Charleston, and the final Siege of Yorktown. At Yorktown, about 1,300 Germans were captured.

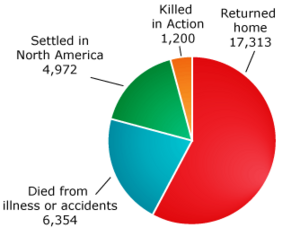

Because most of the German-speaking troops came from Hesse, Americans often called all such soldiers "Hessians." Hesse-Kassel sent over 16,000 troops during the war, and about 6,500 did not return home. Many Hessian soldiers decided to stay in America after the war. For example, Captain Frederick Zeng remained in the United States and became a friend of Philip Schuyler.

Hesse-Kassel signed a treaty with Britain to provide many different types of units. The "jägers" were special light infantry soldiers. They were carefully chosen, well-paid, and very important in the American style of fighting. Hesse-Kassel even recruited African-Americans to serve as soldiers, known as Black Hessians. Most of these 115 black soldiers were drummers or fifers.

General Wilhelm von Knyphausen was a well-known officer from Hesse-Kassel. He led his troops in several important battles. Other notable officers included Colonel Carl von Donop and Colonel Johann Rall. Colonel Rall was fatally wounded at the Battle of Trenton in 1776, and his regiment was captured. Many of these captured soldiers were sent to work on farms in Pennsylvania.

The war lasted longer and was harder than expected. This caused problems for Hesse-Kassel. After the American Revolution, Hesse-Kassel stopped the practice of raising and leasing armies.

Hesse-Hanau's Contribution

Hesse-Hanau was another German state that sent soldiers. Its ruler, William I, offered a regiment to King George III after hearing about the Battle of Bunker Hill. During the war, Hanau provided 2,422 troops, but only 1,441 returned in 1783. Many of these soldiers were volunteers who planned to stay in America after the war. Colonel Wilhelm von Gall was a notable officer from Hesse-Hanau.

Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel's Forces

The Duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was ruled by Duke Charles I. His son, Prince Carl, was married to King George III's sister. In 1775, Prince Carl offered soldiers to help Britain. General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel began recruiting, and Brunswick was the first German state to sign a treaty with Britain in January 1776. They agreed to send 4,000 soldiers.

The Brunswick troops were a large part of General John Burgoyne's army in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. They were often called "Brunswickers" and were known for being very well-trained. General Riedesel's wife, Friederike, traveled with her husband and wrote a journal. This journal is an important record of the Saratoga campaign. After Burgoyne's surrender, 2,431 Brunswickers were held as prisoners until the end of the war.

Brunswick sent 5,723 troops to North America, and 3,015 did not return home. Many Brunswickers became familiar with America during their time as prisoners. When the war ended, they were allowed to stay by both the American Congress and their officers. The Duke of Brunswick received money from the British for each soldier killed. He sometimes reported deserters as dead to get this payment. He even offered six months' pay to soldiers who stayed in America. However, sending troops to North America was not financially successful for Brunswick in the long run.

Ansbach-Bayreuth's Troops

The states of Brandenburg-Ansbach and Brandenburg-Bayreuth were led by Margrave Charles Alexander. They initially sent 1,644 men to the British. These soldiers were described as "the tallest and best-looking" and "better even than the Hessians." They joined General Howe's army in New York and fought in the Philadelphia campaign. Ansbach-Bayreuth troops also served with General Cornwallis at the Siege of Yorktown.

By the end of the war, 2,361 soldiers had been sent from Ansbach-Bayreuth, but fewer than half returned. The Margrave was deeply in debt when the war started. He received over £100,000 for the use of his soldiers. He later sold his states to Prussia and lived in England.

Waldeck's Soldiers

The small German state of Waldeck sometimes hired its soldiers to other countries. Long ago, Waldeck soldiers worked for Venice and fought in Greece, and later for the Dutch.

In 1776, Waldeck agreed to send a group of soldiers to help Britain. This group became known as the 3rd Waldeck Regiment. In 1778, the regiment was sent to defend Pensacola in West Florida. The soldiers were spread out in different locations. Their commander complained that many soldiers became sick and died due to the climate. They also had few supplies and low pay. Waldeck could not recruit new soldiers fast enough to replace those who died. The British and Waldeck forces did not even know that Spain had declared war on Great Britain until they were attacked. Many poorly fed Waldeck soldiers were recruited by the Spanish after the Siege of Pensacola.

Waldeck sent 1,225 men to the war. About 720 were casualties or deserters. A total of 358 Waldeck soldiers died from sickness, and 37 died from combat.

Hanover's Role

The Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg (Hanover) was special because its ruler was King George III of Britain. Five battalions of Hanoverian troops were sent to Gibraltar and Menorca in 1775. This allowed the British soldiers stationed there to go and fight in America. These Hanoverian soldiers helped defend Gibraltar during the longest battle of the war. Later, two regiments from Hanover were sent to British India.

Anhalt-Zerbst's Troops

The Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst, Frederick Augustus, signed a treaty to provide Britain with 1,160 men in 1777. One battalion of 600–700 men arrived in Quebec City, Canada, in May 1778 to guard the city. Another battalion of about 500 soldiers was sent to guard British-occupied New York City in 1780.

German Supporters of the American Cause

German Americans Supporting Patriots

German immigration to the British colonies began in the late 1600s. By the mid-1700s, about 10% of the American colonial population spoke German. Germans were the largest non-British European group in North America. Their level of fitting into British culture varied greatly.

During the French and Indian War in 1756, Britain formed the Royal American Regiment, which mostly included German colonists. Other Germans, like Frederick, Baron de Weissenfels, also immigrated. Weissenfels was a British officer who later joined the Patriots in 1775 and became a lieutenant colonel.

Before the Revolutionary War, some German settlers in the Southern Colonies were Loyalists. Many German colonists chose to remain neutral during the war. However, a significant number supported either the Patriot or Loyalist causes. They fought in local militias and regular army units. A small number returned to Germany after the war.

New American states formed German regiments or filled local militias with German Americans. For example, German colonists in Charleston, South Carolina, created a fusilier company in 1775. Some Germans in Georgia joined General Anthony Wayne's forces.

German Patriots were especially strong in areas where they differed from the large, peaceful Quaker population. Brothers Peter and Frederick Muhlenberg were elected to Congress. Peter even served on George Washington's staff. The German Van Leer Family also had many officers serving under General Anthony Wayne.

Pennsylvania Dutch Military Police

Pennsylvania Dutch people were recruited for the American military police, called the Provost corps. This unit was led by Captain Bartholomew von Heer, a Prussian who had served in a similar role in Europe.

During the Revolutionary War, the Provost Corps had many duties. These included gathering information, securing routes, handling enemy prisoners, and even fighting in battles like the Battle of Springfield. The Provost Corps also protected Washington's headquarters during the Siege of Yorktown. It was one of the last units to be disbanded after the war. The Continental Army sometimes did not welcome the Provost Corps. This was partly because of their duties and because some members spoke little or no English. Six of the provosts had even been Hessian prisoners of war before joining. Today, the Provost Corps is seen as an early version of the modern U.S. Military Police Corps.

The German Regiment

On May 25, 1776, the Second Continental Congress approved the creation of the 8th Maryland Regiment. This unit was also known as the German Battalion or German Regiment. It was made up of ethnic Germans from Maryland and Pennsylvania. Nicholas Haussegger became its colonel. The regiment fought in the Battle of Trenton and the Battle of Princeton. It also took part in campaigns against American Indians. The regiment was disbanded on January 1, 1781.

European Supporters of Congress

George Washington welcomed officers from other European countries into his army. Johann de Kalb was a Bavarian who became a general in the Continental Army. Other Germans came to the United States to use their military skills. Frederick William, Baron de Woedtke, a Prussian officer, received a commission from Congress early in the war. Gustave Rosenthal, an ethnic German from Estonia, became an officer. While some returned home, others like David Ziegler chose to stay and become American citizens.

France also had eight German-speaking regiments with over 2,500 soldiers. The famous Lauzun's Legion included both French and German soldiers. It was even commanded in German.

The most famous German to support the American cause was Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben from Prussia. He came to America on his own and served as Washington's inspector general. General von Steuben is famous for training the Continental Army at Valley Forge. He later wrote the first drill manual for the United States Army. He was granted American citizenship and lived in the United States until his death in 1794.

Von Steuben's home country, Prussia, joined the First League of Armed Neutrality. King Frederick II of Prussia was well-regarded in the United States for his support early in the war. Frederick II held a grudge against King George III. He was interested in trading with the United States and allowed an American agent to buy weapons in Prussia. Frederick predicted America would succeed. He also promised to recognize the United States once France did. Prussia also made it harder for neighboring German states to recruit soldiers for America. Frederick II even blocked roads for troops from Anhalt-Zerbst, delaying British reinforcements.

However, when the War of the Bavarian Succession began, Frederick II became more careful about Prussia's relationship with Britain. American ships were not allowed into Prussian ports. Frederick refused to officially recognize the United States until they signed the Treaty of Paris.

See also