Social background of officers and other ranks in the British Army, 1750–1815 facts for kids

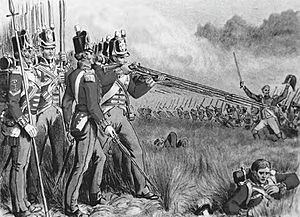

The British Army between 1750 and 1815 was made up of many different people. This period covers the time from the mid-1700s to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Most soldiers joined the army by choice, signing up for a long time. They were often young men from poorer families who couldn't find good jobs.

Non-commissioned officers (NCOs), like sergeants and corporals, were soldiers who had been promoted. They came from the same backgrounds as the regular soldiers. To become an NCO, you needed to be able to read and write. For higher NCO ranks, you also needed to know some basic math.

Most officers, who were in charge, came from wealthier families. About one in ten officers had started as a regular soldier. But many officers were from noble families, or were the sons of landowners, priests, lawyers, doctors, or successful business people. Officers often bought their positions in the army. This system helped keep the officer jobs mostly for people from higher social classes.

Contents

How the British Army Was Set Up

The British Army in this period had two main parts. One part was simply called "the Army." This included the infantry (foot soldiers) and cavalry (soldiers on horseback). This part was controlled by the War Office and led by the Commander-in-Chief of the Forces.

The other part was called "the Ordnance." This included the Royal Artillery (who used cannons) and the Royal Engineers (who built things). The Ordnance was controlled by the Board of Ordnance. These two parts had different uniforms, ways of organizing, ranks, and even different ways of getting promoted. They also had separate budgets and medical services. They only worked together as one big army when they were fighting in a war.

Before 1801, when Ireland joined Britain, "the Army" was also split into a British and an Irish section. The British section was paid for by British taxes, and the Irish section by Irish taxes. Even though they were separate, regiments (groups of soldiers) could move between the two sections.

In the early 1800s, "the Army" had about 13,140 officers and 181,000 other soldiers. The Royal Artillery had 992 officers and 12,500 soldiers.

Who Joined the Army?

The British Army usually got its soldiers through people volunteering to join. Once you joined, you were usually in the army for life, or at least 25 years. This would only end if you died or were badly wounded. During wartime, the army sometimes offered shorter periods of service to get more people to join.

The army often struggled to find enough volunteers. So, during wars, they sometimes forced homeless people or those without jobs to join. There was also a group called the Militia. These soldiers could only serve in England. The government tried to get them to join the regular army, which could fight anywhere.

From 1803, the government also tried drafting men into an "Army of Reserve." The real goal was to get more soldiers for the regular army. But this idea was very unpopular, and they stopped it after three years. The army also hired soldiers from other countries, including Germans and even French royalists, to fight in special foreign regiments.

For a long time, Irish Catholics and Protestants were not allowed to join the Irish army section. However, this rule changed over time. By the late 1700s, many Irish Protestants were officers. The British army also stopped banning Catholics from joining in 1771. In 1775, the Irish army began recruiting both Protestants and Catholics.

People like apprentices, servants, and coal miners were not allowed to join the army. Sailors were kept for the Royal Navy.

Why People Joined the Army

Life as a soldier was very tough. The pay was low, and soldiers were not highly respected in society. Many people joined the army because they were very poor or had nowhere else to go. People at the time thought soldiers were at the bottom of society, just above beggars.

Most new soldiers were young and not married. Older, married men usually hoped for a more stable life. But young farm workers often found it hard to get steady jobs. They might only get seasonal work. About a third of soldiers had been common laborers before joining. Many others had worked as weavers, shoemakers, or tailors.

Studies of British soldiers in North America during the American Revolutionary War showed that more recruits came from areas where the economy was unstable. The Industrial Revolution was changing Britain, and many people were losing their jobs. About one-fifth of recruits had worked in the textile industry. Many craftsmen who joined had jobs that were being hurt by new factories, like shoemakers. Trades with seasonal work, like bricklayers, also provided many soldiers. People with stable jobs, like miners, rarely joined the army.

Non-Commissioned Officers

Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) in the infantry were sergeants and corporals. They directly led the soldiers. Officers also gave NCOs many daily tasks, like managing the company's paperwork. Higher NCO roles, like colour sergeant (started in 1813) and sergeant major, were special appointments rather than ranks.

Becoming a sergeant major was a big achievement for an NCO. They even wore uniforms that looked like an officer's. To get this job, you had to be good at training soldiers. You also needed to be skilled at writing and counting.

There wasn't one single way to become an NCO. Being able to read and write was a must. Surprisingly, many soldiers became sergeants after only one year of service. In the cavalry, things were a bit different. Until 1810, each cavalry troop had a "troop quartermaster." This rank was between an officer and an NCO. Over time, it became a common promotion for sergeants. However, some poor young gentlemen who couldn't afford to buy an officer's job would also try to become troop quartermasters.

Many senior NCOs were leaders in Masonic lodges. These groups were important in the social life of many regiments.

Soldiers Who Became Officers

About one in ten officers had started as a regular soldier before becoming an officer. This was a much higher number than later in the 1800s. Back then, becoming an officer was mostly for people from a very specific social group.

Soldiers who became officers usually fit into three groups:

- Experienced Sergeants: Many were older, skilled sergeants who were promoted to help with discipline or administration. For example, adjutants (who helped with daily tasks) were often promoted from the ranks. By the late 1700s, quartermasters (who handled supplies) were almost always sergeants. Very skilled sergeants could even become lieutenants right away, skipping the lowest officer rank. Most of these officers had served for many years. It was very hard for them to get promoted to higher officer ranks.

- Battlefield Promotions: Some soldiers became officers because they showed great bravery in battle.

- Volunteers: These were young gentlemen from the same social background as most officers. But they didn't have enough money or connections to buy an officer's job. They joined as volunteers, hoping to be promoted without having to buy their position.

Officers and Their Backgrounds

To become an officer in "the Army," the rules seemed simple. You had to be between 16 and 21 years old, able to read and write, and have a recommendation letter from a senior officer. Soldiers who were promoted to officer didn't have to follow the age rule.

But in reality, you needed to come from a "good family" and have money or powerful friends. There was no official military training required. The Royal Military College, Sandhurst was founded in 1801, but you didn't have to go there to become an officer. Two-thirds of officers in the infantry and cavalry bought their positions. The other third got their jobs as a reward for long service, through connections, or if they were soldiers promoted from the ranks.

The "purchase system" was closely tied to politics. It was believed that this system would make sure officers were loyal to the social elite, not just the King. This system was used until 1871. The King tried to control the system. By the mid-1700s, you couldn't buy the rank of colonel or higher. These top jobs were given out by the King.

It was hard to control the cost of commissions or create a fair promotion system. A young man with money and connections could become a lieutenant colonel very quickly. But in 1795, the Duke of York became commander-in-chief. He put strict rules in place. For example, an officer had to serve two years as a junior officer before buying a captain's job. The regiment's colonel also had to approve.

An officer usually had the right to be promoted within his own regiment based on how long he had served. But if he couldn't afford the next rank, someone from another regiment who could pay might buy it and transfer in. This helped rich officers with good connections. If an officer died in battle, his position became open. Someone could then be promoted without buying the job. So, wars gave skilled officers without much money a better chance to move up. These promotions were based on seniority (how long you had served). So, it was difficult, but not impossible, to advance just by serving a long time.

Officers in the infantry and cavalry came from many different social groups. But noble families were very powerful. Even though they held only about a quarter of all officer jobs in the 1700s, half of the colonels and generals were from these noble families. Many sons of officers also became officers. But because they didn't have the same social status or money as the rich families, they moved up slower. Soldiers who became officers rarely got past the lowest officer ranks. Most officers were skilled professionals who had served a long time. They didn't have much private money and lived on their army pay. However, the lifestyle expected of an officer often cost more than their pay, leading to money problems.

To become an officer in the Royal Artillery or Royal Engineers, you had to pass exams from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich. Students usually studied for 18-24 months. If they passed their final exam and there was an open job, they became a junior officer. The best students became engineers, and the rest became gunners. The "Ordnance corps" did not use the purchase system. Promotions were strictly based on seniority. This meant promotions were very slow. Since there were no pensions or jobs to sell, gunners and engineers often stayed in the army for a very long time, even when they were old and not fit for fighting. This made it even harder for junior officers to get promoted.

Noble Families in the Army

Some historians used to think that the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars was mostly led by noble families. But historians Robert Burnham and Ron McGuigan say this is a myth. In 1814, there were 10,590 officers in the army. Only about 2% of them, or 224 people, were members of the British nobility.

The table below shows how many members of noble families served in the British Army between 1805 and 1816:

| Title | 1805 | 1806 | 1807 | 1808 | 1809 | 1810 | 1811 | 1812 | 1813 | 1814 | 1815 | 1816 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Duke | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Marquess | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Earl | 17 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 26 | 25 |

| Viscount | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| Baron | 20 | 18 | 21 | 17 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 19 | 15 | 18 | 19 | 17 |

| Courtesy lord | 15 | 17 | 16 | 20 | 17 | 13 | 17 | 16 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 17 |

| Honourable | 127 | 113 | 144 | 138 | 146 | 147 | 143 | 151 | 138 | 144 | 131 | 131 |

| Total | 198 | 184 | 220 | 211 | 219 | 219 | 217 | 227 | 215 | 224 | 206 | 205 |

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |