Colonial Williamsburg facts for kids

|

Williamsburg Historic District/Williamsburg Historical Triangle

|

|

|

From top to bottom (left to right): View of the reconstructed Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street; Gardens at the Governor's Palace; Carriage; Capitol Building at night

|

|

| Location | Bounded by Francis, Waller, Nicholson, N. England, Lafayette, and Nassau Sts., Williamsburg, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Area | 173 acres (70 ha) |

| Built | 1699 |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000925 |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | October 9, 1960 |

Colonial Williamsburg is a special place in Williamsburg, Virginia. It's like a giant outdoor museum where you can step back in time. The historic area covers about 301 acres. It has hundreds of buildings from the 1700s, when Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia.

You can also see buildings from the 1600s and 1800s. The streets look just like they did long ago. People who work there dress and talk like they did in the 18th century. They help you imagine what life was like back then.

In the late 1920s, people wanted to restore Williamsburg. They wanted to celebrate America's early history. Important people like Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller Jr. helped make it happen.

Colonial Williamsburg is part of the Historic Triangle in Virginia. This triangle also includes Jamestown and Yorktown. In 1960, Colonial Williamsburg was named a National Historic Landmark District. This means it's a very important historical site.

Contents

Exploring Colonial Williamsburg

The main part of Colonial Williamsburg is along Duke of Gloucester Street. This street is mostly flat. Cars are not allowed on Duke of Gloucester Street during the day. Instead, people walk, bike, or ride in horse-drawn carriages.

Many old buildings have been carefully restored. They look just like they did in the 1700s. Some buildings that were missing have been rebuilt exactly where they used to be. You can also see gardens, kitchens, and other small buildings.

Some buildings and most gardens are open for visitors. A few buildings are still used as homes for employees or special guests.

Important buildings to see include the Raleigh Tavern, the Capitol, and the Governor's Palace. These were all rebuilt. The Courthouse, the Wythe House, and the Peyton Randolph House are original buildings. The Bruton Parish Church is also original and still used today.

You can find four taverns that are now restaurants or inns. There are also workshops where you can see craftsmen at work. They do trades like printing, shoemaking, and blacksmithing. You can also find shops selling souvenirs and old-fashioned toys.

Some houses are open for tours, like the Peyton Randolph House. Public buildings like the Courthouse and the Public Gaol (jail) are also open. Even some of the pirate Blackbeard's crew were held in the Gaol!

Colonial Williamsburg also includes Merchants Square. This area has shops and restaurants built in an old style. Nearby are two museums: the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum.

Williamsburg's Past

In the 1600s, Jamestown was the capital of Virginia. But the government building burned down in 1698. So, the leaders moved their meetings to a place called Middle Plantation. This ended Jamestown's 92 years as the capital.

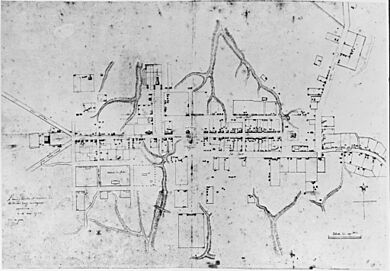

In 1699, Middle Plantation was renamed Williamsburg. This was to honor William III of England. Governor Francis Nicholson helped plan the city. He made sure it had a clear grid of streets. The main street was named Duke of Gloucester Street.

For 81 years in the 1700s, Williamsburg was the center of Virginia. Important leaders like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson worked there. They helped shape the ideas of government for the new United States.

In 1780, the government moved to Richmond. This was because Richmond was more central and safer from British attacks. Richmond is still Virginia's capital today.

How Colonial Williamsburg Was Restored

After the government moved, Williamsburg became quieter. Many businesses left. The town kept much of its old look, though. During the American Civil War, the town was protected. So, it didn't suffer as much damage as other Southern cities.

Over time, some old buildings were changed or fell apart. But the town still attracted tourists. By the early 1900s, many historic buildings were in bad shape.

Dr. Goodwin and the Rockefellers' Vision

Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin was a church leader in Williamsburg. He returned to the town in 1923. He saw that many colonial buildings were falling apart. He wanted to save them.

Goodwin worked hard to get people interested. He eventually got help from John D. Rockefeller Jr., a very wealthy man. Rockefeller's wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, also played a role.

Rockefeller first helped buy the George Wythe House. Then, he bought another house, the Ludwell–Paradise House. On November 22, 1927, Rockefeller decided to support a huge project. He would help restore the entire town.

Rockefeller and Goodwin kept their plans secret at first. They didn't want property prices to go up. They quietly bought houses and land. In June 1928, they finally announced their plans. They wanted the town's citizens to agree and help. The project needed a new high school and public spaces.

Some people worried about selling their homes. They wondered if they would still "own their town." To help, the restoration offered people a deal. They could sell their homes but live in them for free for the rest of their lives.

Rebuilding the Past

The restoration project decided to rebuild parts of the town. They wanted to show what shops, taverns, and markets looked like long ago.

The first main architect was William G. Perry. Many other architects helped guide the project. During the restoration, 720 buildings built after 1790 were taken down. Some old 18th-century homes were also taken down, which caused some debate.

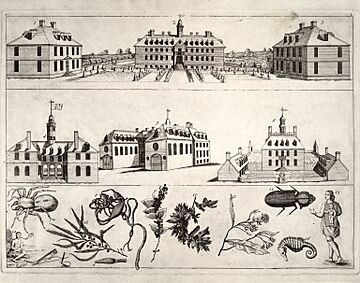

The Governor's Palace and the Capitol building were rebuilt. They used old drawings, descriptions, and photos to make them look accurate. The gardens were also recreated in the old style.

The Capitol building you see today was finished in 1934. It's a copy of the 1705 building. The original Capitol burned down. A second Capitol was built, where important events happened. For example, Patrick Henry spoke against the Stamp Act there.

Out of about 500 buildings, 88 are original. This includes small buildings like smokehouses. The Capitol and Governor's Palace are considered "reconstructions" because they were rebuilt on their original foundations. The Wren Building at William & Mary was rebuilt on its original foundation too.

On the west side of town, new shops were built in the 1930s. This area was called Merchants Square. It was for local businesses that had to move.

Protecting the Views

Colonial Williamsburg also bought land around the historic area. This was to keep the natural views looking like they did in the 1700s. This helps visitors feel like they are stepping back in time.

The Colonial Parkway was built to go under the historic area. This helps keep modern roads from spoiling the view. Even major highways were moved or designed to protect the historic feel.

Dr. Goodwin helped with these efforts. The Colonial Williamsburg headquarters building, built in 1940, is named The Goodwin Building in his honor.

Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, Interstate 64 was built. Land around it was also protected. This way, visitors don't see modern buildings before reaching the Visitor's Center.

The old train station was replaced with a new one in a colonial style. This new station was placed out of sight but still close to the historic area.

Colonial Williamsburg Today

Colonial Williamsburg is an open-air museum. It has people called "interpreters" who dress in old costumes. They explain and show what daily life was like long ago. They work, dress, and talk like people from colonial times.

Unlike some other museums, you can walk through Colonial Williamsburg's historic district for free. You can do this at any time of day. You only pay if you want to go inside the historic buildings. Inside, you can see craft demonstrations or watch special performances.

The Visitor Center has a short film called Williamsburg: the Story of a Patriot. It first showed in 1957. Visitors park at the Visitor Center because cars are not allowed in the historic area. Shuttle buses take visitors around the historic district.

The costumed interpreters always wear historical clothes now. In 1973, they tried wearing modern outfits, but visitors didn't like it. So, they went back to historical costumes.

Many reenactments are shared online. Colonial Williamsburg also has special themes. These might be about the town's founding or visits from famous leaders like General George Washington.

Some interpreters work with animals. The Colonial Williamsburg Rare Breed Program helps save and show animals that lived during colonial times.

Colonial Williamsburg is partly pet-friendly. Leashed pets can be in outdoor areas and on shuttle buses. But they are not allowed inside buildings, except the visitor center.

Grand Illumination Celebration

The Grand Illumination is a big outdoor celebration. It happens every year on the first Sunday of December. Thousands of Christmas lights are turned on at the same time.

This ceremony started in 1935. It's based on an old tradition of putting candles in windows. People did this to celebrate special events, like winning a war. The Grand Illumination also has fireworks displays. These are like the fireworks used in the 1700s for big occasions.

Learning and Outreach

Colonial Williamsburg offers programs for teachers. These workshops help educators learn about early American history. They can meet historians and interpreters. They also prepare materials for their classrooms.

There are also "Electronic Field Trips." These are multimedia presentations for schools. Each program is about a history topic. It includes lesson plans and online activities. Schools can even call in during live broadcasts to talk with interpreters.

In 2007, Colonial Williamsburg launched iCitizenForum.com. This website has historical documents and user-made content like blogs. It encourages discussions about what it means to be a citizen in a democracy.

The John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library is a key part of Colonial Williamsburg. It has special collections of old books, manuscripts, and maps. It also has photos and media.

Souvenirs and Shops

You can buy colonial-style craft items in the historic area stores. Many shops sell things like soaps, knitted hats, and handmade wooden toys.

How Colonial Williamsburg is Run

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation owns and runs Colonial Williamsburg. It's a non-profit group. The Rockefeller family first provided money for it. Other people like Lila and DeWitt Wallace also gave a lot of money.

The main goal is to recreate the old colonial environment. It also aims to teach people about how America's ideas of liberty and equality began.

Cliff Fleet became the president and CEO of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 2019.

Visitors and Challenges

In 1985, Colonial Williamsburg had its highest number of visitors, with 1.1 million people. After some years of fewer visitors, attendance started to go up again around 2007. This was helped by the "Revolutionary City" programs, which are live street performances.

Colonial Williamsburg faces financial challenges. It gets money from tickets and shops. But it loses money from its hotels. It also gets funds from investments and fundraising. The foundation has sold some land and properties it no longer needed.