List of delegates to the Continental Congress facts for kids

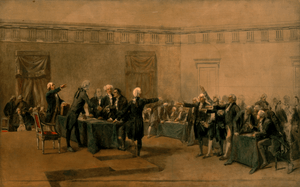

The Continental Congress was a group of leaders, called delegates, from the Thirteen Colonies in America. They met to talk and act together for the people of these colonies, which later became the United States. This group is mainly known for the First Continental Congress in 1774 and the Second Continental Congress from 1775 to 1781. It also refers to the Congress of the Confederation from 1781 to 1789. During these years, the Continental Congress acted as the main law-making and leadership body for the new U.S. government.

This Congress was a single body, meaning it had only one house, unlike today's U.S. Congress which has two (the House of Representatives and the Senate). Its members were chosen by the law-making groups (legislatures) in each state. Many of the delegates who attended the Second Continental Congress had also been part of the First. Over time, 343 different men served as delegates from 1774 to 1789.

Why the Congress Met

The First Continental Congress met in 1774 because the British Parliament had passed some very unfair laws called the Intolerable Acts. These laws made the colonists very angry. The 56 delegates at this meeting wanted to fix the bad relationship between Britain and its American colonies.

They decided to stop buying British goods (this was called the Continental Association). They also sent a special message to King George III, asking him to address their complaints. They agreed to meet again in May 1775 if things didn't get better.

When the delegates met for the Second Continental Congress in 1775, the Revolutionary War had already started. Some still hoped to make peace with Great Britain. But more and more people wanted independence. The Congress sent one last plea for peace to King George III, called the Olive Branch Petition. At the same time, they also wrote a strong statement saying they were ready to fight for their freedom. They declared, "Our cause is just. Our union is perfect... being with one mind resolved to die freemen rather than to live slaves..."

From the very beginning, the Congress acted like a real national government. It created the Continental Army, planned war strategies, and sent diplomats to other countries. On July 2, 1776, the Congress voted to become a new, independent country. Two days later, on July 4, they officially approved the Declaration of Independence.

After declaring independence, the Congress served as the temporary government of the United States until March 1, 1781. During this time, they successfully managed the war. They also wrote the Articles of Confederation, which was the first U.S. Constitution. They worked to get other countries to recognize and support the new nation. They also helped settle land claims in the western areas of the Appalachian Mountains.

When the Articles of Confederation were approved by all 13 states on March 1, 1781, the Continental Congress changed its name to the Congress of the Confederation. This new Congress guided the young nation through the end of the Revolutionary War. Under the Articles, the Confederation Congress had limited power. It could declare war, sign treaties, and solve arguments between states. It could also borrow or print money. However, it could not collect taxes, and it couldn't force states to follow its decisions. This Congress met eight times before it was replaced in 1789. That's when the current United States Congress became the nation's law-making body under a new Constitution.

How Delegates Were Chosen

Article V of the Articles of Confederation explained how delegates were chosen for Congress each year. The law-making groups in each state would elect their delegates. Their terms started on the first Monday in November every year.

Each state could send between two and seven delegates. No person could serve as a delegate for more than three years within any six-year period. State legislatures could also remove or replace their delegates at any time. Before 1781, delegates served as long as their state legislature wanted them to. There were no set term limits or start and end dates for their service.

The Articles of Confederation stated:

For the most convenient management of the general interests of the United States, delegates shall be annually appointed in such manner as the legislatures of each State shall direct, to meet in Congress on the first Monday in November, in every year, with a power reserved to each State to recall its delegates, or any of them, at any time within the year, and to send others in their stead for the remainder of the year.

No State shall be represented in Congress by less than two, nor more than seven members; and no person shall be capable of being a delegate for more than three years in any term of six years; nor shall any person, being a delegate, be capable of holding any office under the United States, for which he, or another for his benefit, receives any salary, fees or emolument of any kind.

Each State shall maintain its own delegates in a meeting of the States, and while they act as members of the committee of the States.

In determining questions in the United States in Congress assembled, each State shall have one vote.

Freedom of speech and debate in Congress shall not be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Congress, and the members of Congress shall be protected in their persons from arrests or imprisonments, during the time of their going to and from, and attendance on Congress, except for treason, felony, or breach of the peace.

See also

- Founding Fathers of the United States, includes a listing of which Founding Fathers signed one or more of the era's formative state documents

- Journals of the Continental Congress

- Charles Thomson, secretary of the Continental Congress

- History of the United States (1776–1789)

- Perpetual Union

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |