Stephen Hopkins (politician) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stephen Hopkins

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 28th, 30th, 32nd, and 34th Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1755–1757 |

|

| Preceded by | William Greene |

| Succeeded by | William Greene |

| In office 1758–1762 |

|

| Preceded by | William Greene |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Ward |

| In office 1763–1765 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel Ward |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Ward |

| In office 1767–1768 |

|

| Preceded by | Samuel Ward |

| Succeeded by | Josias Lyndon |

| 3rd, 5th, and 17th Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court | |

| In office May 1751 – May 1755 |

|

| Preceded by | Joshua Babcock |

| Succeeded by | Francis Willet |

| In office August 1755 – May 1756 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis Willet |

| Succeeded by | John Gardner |

| In office June 1770 – August 1776 |

|

| Preceded by | James Helme |

| Succeeded by | John Cooke |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 7, 1707 Providence, Colony of Rhode Island |

| Died | July 13, 1785 (aged 78) Providence, State of Rhode Island |

| Spouses | (1) Sarah Scott (2) Anne Smith |

| Relations | Martha Hopkins Round (sister) Esek Hopkins, brother |

| Occupation | Surveyor, Politician, Chief Justice, Congressional Delegate, Governor |

| Known for | signer of the United States Declaration of Independence |

| Signature | |

Stephen Hopkins (born March 7, 1707 – died July 13, 1785) was an important person in early American history. He is known as a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations many times. He was also a chief justice for the Rhode Island Supreme Court. Most famously, he was one of the people who signed the Declaration of Independence.

Stephen Hopkins came from a well-known family in Rhode Island. His great-grandfather, Thomas Hopkins, was one of the first settlers in Providence Plantations. He sailed from England in 1635. His cousin, Benedict Arnold, became the first governor of the Rhode Island colony.

As a child, Stephen loved to read. He studied science, math, and literature. He became a surveyor and an astronomer. He even helped measure the transit of Venus across the Sun in 1769. He started working in public service at age 23. He was a justice of the peace in Scituate, Rhode Island. He also served as a judge and speaker of the House of Deputies. Besides his public work, he owned part of an iron factory. He was also a successful merchant.

One big political issue in his time was about money. Some people wanted to use paper money, while others wanted hard coins. Stephen Hopkins supported paper money. His political rival, Samuel Ward, wanted hard coins. Their arguments became so strong that they both agreed not to run for governor in 1768. This allowed Josias Lyndon to become governor as a compromise.

In 1770, Hopkins became chief justice again. He played a key role in how Rhode Island handled the 1772 Gaspee Affair. This was when angry Rhode Island citizens burned a British ship. In 1774, he became one of Rhode Island's delegates to the First Continental Congress. He was already famous for writing a pamphlet called The Rights of Colonies Examined. This paper criticized Britain's taxes.

Hopkins signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. His hands were shaking because of a condition called palsy. He held his right hand with his left to sign it. He famously said, "My hand trembles, but my heart does not." He left the Continental Congress in September 1776 due to his health. He was a strong supporter of the College of Rhode Island (now Brown University). He became its first leader, called chancellor. He died in Providence in 1785 at age 78. He is buried in the North Burial Ground. Many people call him Rhode Island's greatest leader.

Contents

Stephen Hopkins: A Founding Father

Early Life and Learning

Stephen Hopkins was born in Providence, in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He was the second of nine children. His grandfather, William Hopkins, was a very important person in the colony. He served as a deputy and speaker for over 40 years. Stephen's great-grandfather, Thomas Hopkins, was one of the first settlers in Providence.

Stephen spent his early life in a wooded area of Providence called Chopmist Hill. This area later became Scituate, Rhode Island. There were no schools there at the time. But Stephen had access to family books and a small library. He loved to read everything he could find. Historians say he was a very serious student.

Stephen learned surveying skills from his grandfather, Samuel Wilkinson. He used these skills to map the streets of Scituate and later Providence. When he was 19, his father gave him 70 acres of land. His grandfather gave him another 90 acres.

He was also very interested in astronomy and science. He helped observe the transit of Venus on June 3, 1769. This is when Venus passes directly between the Sun and Earth. An observatory was built in Providence for this event. Stephen Hopkins and other scientists used special tools to watch it. This helped them figure out the exact location of Providence. He was also chosen to join the American Philosophical Society in 1768.

From Surveyor to Politician

Stephen Hopkins began his public service in 1730 when he was 23. He became a justice of the peace in Scituate. He held this job until 1735. He also worked as the town clerk for 11 years. In 1742, he moved to Providence.

He became a judge in the Inferior Court of Common Pleas from 1736 to 1746. He was also the clerk of that court for five years. During this time, he was also the president of the Town Council and a deputy. He served as speaker of the House of Deputies for two years.

In Providence, he focused on business. He became a merchant who built and owned ships. He also owned part of a privateering ship called Reprisal in 1745.

Later in life, Hopkins became a manufacturer. He partnered with the Brown brothers (Moses, Nicholas, Joseph, and John). They started the Hope Furnace, an iron works. This factory made iron and cannons for the Revolutionary War. Stephen's son, Rufus Hopkins, managed this business for 40 years.

Governor of Rhode Island

In 1755, Stephen Hopkins was elected governor for the first time. He won against William Greene. This year was busy with laws and preparing for war with France. Hopkins and Daniel Updike went to the Albany Congress in New York. They discussed how the colonies could defend themselves together. They also met with Native American tribes to get their help against the French. They looked at Benjamin Franklin's idea for uniting the colonies, but it was not accepted then.

After two years, Hopkins lost the election to William Greene. But Greene died in 1758, and Hopkins became governor again. A big issue was whether to use hard money (coins) or paper money. Hopkins supported paper money. He also supported Providence's interests over Newport's. He had a strong rivalry with Samuel Ward from Westerly. Ward supported hard money and Newport. Their rivalry was so intense that Hopkins sued Ward, but he lost the case.

For ten years, Hopkins and Ward took turns being governor. Ward represented the wealth of Newport and other southern areas. Hopkins represented the growing power of Providence. People said they were like gladiators fighting each other. Ward was elected governor in 1762.

In 1763, Hopkins won back the governorship. The next year, both men started to try to get along. Ward suggested they both quit running for governor. Hopkins, without knowing about Ward's letter, invited Ward to be deputy governor. Neither accepted the other's offer, but it was a start for them to work together.

Fighting for Freedom: The Stamp Act

Near the end of Hopkins' term, a very important issue came up. This issue brought everyone together. In 1765, the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act. This law was a way to tax the colonies. It said that all legal papers and newspapers had to be printed on special stamped paper. This paper was sold by British officers at a set price. Parliament also added taxes on sugar, coffee, and other goods. They also said that lumber and iron from the colonies could only be sent to England.

The colonists were very angry about this act. Samuel Adams of Massachusetts asked all the colonies to send delegates to a meeting in New York. They wanted to discuss how to get rid of these unfair taxes. In August 1765, Rhode Island passed resolutions against the act. The Stamp Act was eventually removed, and the colonies celebrated in May 1766. This delayed the fight for independence, but it did not stop it.

A College for Rhode Island

Another important event brought Ward and Hopkins together. In 1764, a law was passed to create a college in Rhode Island. This college later became Brown University. Both men strongly supported having a college in the colony. They both became trustees. Stephen Hopkins was the first name on the list of 36 trustees. He also became one of the college's most generous supporters. He was the school's first chancellor until he died in 1785.

In the 1767 election, Hopkins beat Ward by a large amount. In 1768, Hopkins suggested to Ward that they both step aside. They agreed to choose a new governor together. Josias Lyndon was elected governor. After this, Ward and Hopkins became good friends for the rest of their lives.

Standing Up for the Colonies

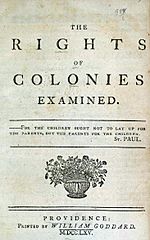

In November 1764, Stephen Hopkins published a pamphlet called The Rights of Colonies Examined. This paper was mainly about the Stamp Act. It made Hopkins famous as a leader for independence. It was shared widely and criticized British taxes. The paper started by saying, "Liberty is the greatest blessing that men enjoy, and slavery the heaviest curse that human nature is capable of." It then explained why the American colonies should have more rights. Many people in the colonies liked it. Historians say it was a very important document before the Revolutionary War.

The Gaspee Affair

In May 1747, Hopkins became a judge on the Rhode Island Superior Court. In 1751, he became the third Chief Justice of this court. He held this job until 1755 when he became governor. After serving as governor for nine years, he was again made Chief Justice in 1770. He served until 1775, while also being a delegate to the Continental Congress.

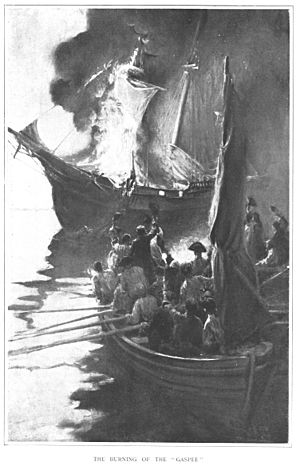

One of the most important events during his time as Chief Justice was the Gaspee Affair. In March 1772, a British ship called the Gaspee was bothering commercial ships in Narragansett Bay. Rhode Island officials, including Chief Justice Hopkins, were worried. On the night of June 9–10, a group of angry colonists attacked the ship and burned it.

Officially, Rhode Island leaders said they were upset and would help find the people responsible. But secretly, Hopkins and others tried to stop anyone from finding the attackers. The British government started an investigation. They wanted to send anyone found guilty to England for trial. This made the colonists even angrier. It led to the creation of the Committees of Correspondence. These groups helped colonies communicate and plan.

Hopkins and other leaders worked together to hide evidence and threaten witnesses. Most Rhode Island citizens supported the attackers and kept quiet. A year later, the investigation ended without anyone being charged.

Joining the Continental Congress

In 1774, the First Continental Congress met. Both Stephen Hopkins and Samuel Ward were chosen as delegates from Rhode Island. Hopkins, at 68, was older than almost all the other delegates. He was one of only two delegates who had also attended the Albany Congress 20 years earlier. His hands shook a lot because of his palsy, making it hard for him to write.

The Congress met to protest Britain's actions and protect the colonies' rights. Both Hopkins and Ward believed that independence would only come through war. Hopkins told his fellow delegates, "Powder and ball will decide this question." He believed that only fighting would solve the problem.

Hopkins was chosen again for the Second Continental Congress. This meeting started in May 1775, after the battles of Lexington and Concord. This Congress managed the war and eventually declared independence. Hopkins was very helpful on a committee that planned for a navy. He knew a lot about shipping. He helped create the rules for the new Continental Navy. The first American naval ships were launched in February 1776. Hopkins also helped his brother, Esek Hopkins, become the first commander of the new navy.

Signing the Declaration of Independence

On May 4, 1776, Rhode Island declared its independence from Great Britain. Two months later, on July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted the United States Declaration of Independence. Stephen Hopkins, though his hands trembled from palsy, signed the document. He held his right hand with his left and said, "my hand trembles, but my heart does not." The famous painting Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull shows Hopkins standing in the back with a hat.

Stephen Hopkins and Slavery

Stephen Hopkins owned enslaved people, like many signers of the Declaration of Independence. In his 1760 will, he mentioned five enslaved people. He left them to close family members and gave instructions for their care. This was unusual for slave owners at the time.

On October 28, 1772, Hopkins freed an enslaved man named Saint Jago. In the document, he wrote that keeping "rational Creatures in Bondage" was against God's will. However, he did not free an enslaved woman named Fibbo. He believed she had children who needed her care. This decision cost him his membership in the Quaker church. It seems his other enslaved people were freed after his death.

In 1774, Hopkins introduced a bill in the Rhode Island Assembly. This bill stopped the import of enslaved people into the colony. This was one of the first laws against the slave trade in the United States. Quakers, who were a large group in Rhode Island, put pressure on leaders to end slavery. Hopkins' second wife was a Quaker, and he became an active follower of their faith. This may have influenced him to free enslaved people and propose his anti-slavery bill.

Later Life and Legacy

In September 1776, Stephen Hopkins' health got worse. He had to leave the Continental Congress and go home to Rhode Island. But he continued to be an active member of Rhode Island's general assembly from 1777 to 1779. He died at his home in Providence on July 13, 1785, at age 78. He is buried in the North Burial Ground there.

Hopkins helped start the Providence Library Company in 1753. He was also a member of the Philosophical Society of Newport. The town of Hopkinton, Rhode Island, was named after him. Also, a ship named SS Stephen Hopkins was the first U.S. ship to sink a German warship in World War II.

Even though he mostly taught himself, Hopkins was very important in starting the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (now Brown University). He was a founding trustee and the school's first chancellor from 1764 to 1785. His home, the Governor Stephen Hopkins House, is now a U.S. National Historic Landmark. It is located at 15 Hopkins Street in Providence.

Many historians have praised Stephen Hopkins. One historian called him "the greatest statesman of Rhode Island."

Family Life

Stephen Hopkins married Sarah Scott in 1726. She was related to Richard Scott, one of the first Quaker settlers in Providence. She was also related to the famous religious leader Anne Hutchinson. Stephen and Sarah had seven children, and five of them lived to be adults. Sarah died in 1753. Hopkins then married Anne Smith. They did not have children together. Stephen's younger brother, Esek Hopkins, became the first commander of the Continental Navy. His other brother, William, became a well-known merchant. Stephen's cousin was the Quaker preacher Jemima Wilkinson.

See also

In Spanish: Stephen Hopkins para niños

In Spanish: Stephen Hopkins para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |