Briggs v. Elliott facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Briggs v. Elliott |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Decided January 28, 1952 | |

| Full case name | Harry Briggs, Jr. et al. v. R.W. Elliott, chairman, et al. |

| Citations | 342 U.S. 350 (more)

72 S. Ct. 327; 96 L. Ed. 2d 392; 1952 U.S. LEXIS 2486

|

| Prior history |

|

| Subsequent history |

|

| Holding | |

| In order that the Supreme Court may have the benefit of the views of the district court upon the additional facts brought out in the appellees report on the implementation of district court's mandate to equalize segregated South Carolina schools, and that the district court may have the opportunity to take whatever action it may deem appropriate in light of that report, the judgment is vacated and the case is remanded for further proceedings. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Per curiam. | |

| Dissent | Black, joined by Douglas |

| Laws applied | |

| 28 U.S.C. (Supp. IV) § 1253, S.C. Const., Art. XI, § 7; S.C. Code § 5377 (1942) | |

Briggs v. Elliott was a very important court case from 1952. It challenged the rule of separating students by race in schools in Summerton, South Carolina. This case was one of five that later became part of the famous Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954. In Brown, the U.S. Supreme Court said that separating students by race in public schools was against the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This amendment guarantees equal protection under the law for all citizens.

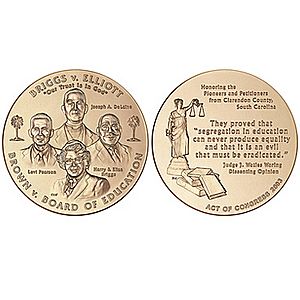

After the Brown decision, a court order was issued. This order said that South Carolina's school segregation law was unconstitutional. It also required the state's schools to integrate, meaning students of all races could attend the same schools. Several key people involved in the Briggs case, including Harry and Eliza Briggs, Reverend Joseph A. DeLaine, and Levi Pearson, were honored with Congressional Gold Medals in 2003.

Contents

Why the Case Started

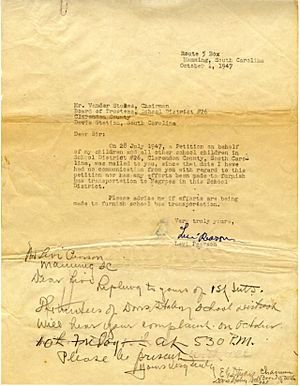

The story of Briggs v. Elliott began in 1947. A man named Levi Pearson lived in Clarendon County, South Carolina. He wrote a letter to the local school district. He asked for school bus transportation for black children, just like white children received.

At that time, schools for white children in Clarendon County had many advantages. They had a teacher for every grade and small class sizes. Their schools were made of brick, had heat, indoor toilets, and modern textbooks. They also had gyms, auditoriums, and libraries.

However, schools for black children were very different. They were often in old hunting lodges or cabins. Students had to bring coal or wood for heat. They bought textbooks that white students had already used. For restrooms, they used outdoor toilets and carried water from wells. Some classes were very large, with one first-grade teacher having 67 students.

Before Pearson's letter, the school board used all 30 of its buses for white children. This meant Pearson's children had to travel nine miles one way to reach the nearest black school. Many black children in Clarendon County had difficult journeys to school. Some even had to row boats across water. In a nearby community, some children walked up to 16 miles each day.

Levi Pearson, his brother Hammett, and a neighbor, Joseph Lemon, raised money to buy a used school bus. But the bus often needed repairs. So, they asked the school superintendent, Roderick M. Elliott, for a county-funded bus. Superintendent Elliott refused. He said black citizens didn't pay enough taxes to justify a bus.

To help with his efforts, Pearson hired lawyer Harold Boulware and Thurgood Marshall. Marshall was a rising star with the NAACP. Marshall argued that since white students had buses, denying them to black students violated the "separate but equal" rule from an earlier case, Plessy v. Ferguson.

Pearson's lawsuit, Pearson v. Clarendon County, faced immediate problems. People shot guns into his home. Local banks refused to give him loans for farming. Other farmers wouldn't lend him equipment.

In 1948, Pearson v. Clarendon County was dismissed. This happened because the superintendent pointed out that Pearson's property crossed different school district lines. Levi Pearson's brother, Hammett, then offered to take his place in the lawsuit.

The NAACP lawyers decided to change their goal. Instead of just asking for equal transportation, they aimed for complete desegregation. In 1949, the NAACP agreed to support a case asking for equal education in Clarendon County. Reverend Joseph Armstrong DeLaine and civil rights worker Modjeska Monteith Simkins helped organize a local petition. More than 100 Clarendon residents signed it.

More People Join the Lawsuit

Others agreed to join the lawsuit. Harry Briggs, a service station attendant, and Eliza Briggs, a maid, became the main people named in the case. Their last name gave the case its title: Briggs v. Elliott. Elliott was the defendant, representing the school board.

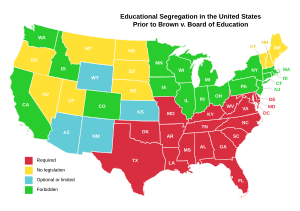

When the Briggs case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, South Carolina was one of 17 states that required schools to be segregated. South Carolina law demanded complete separation. Its 1896 Constitution stated: "Separate schools shall be provided for children of the white and colored races, and no child of either race shall ever be permitted to attend a school provided for children of the other race."

There was little argument about whether the schools in Clarendon County were unequal. At the start of the court hearings, the defendants admitted that "the educational facilities... for colored pupils are not substantially equal to those afforded for white pupils."

Court Proceedings

The case was supposed to be heard by Judge Julius Waring of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina. However, Judge Waring suggested to Thurgood Marshall that the case should be expanded. Instead of just asking for equal facilities, he suggested asking for school segregation itself to be declared unconstitutional.

Three-Judge Panel Decision

Both Judge Waring and Marshall expected to lose the case at this level. They thought it would then go to the U.S. Supreme Court. As predicted, a panel of three judges heard the case. They voted 2–1 that segregation was legal. Judge Waring disagreed, writing that "segregation is per se inequality," meaning it is unequal by its very nature. The other two judges were John J. Parker and George Timmerman. The panel did order the schools for African American students to be made equal, as everyone agreed they were not.

The Briggs case was important for including evidence from Kenneth and Mamie Clark. These psychologists used dolls to study how children felt about race. In their tests, African American students in segregated schools were shown a white doll and an African American doll. When most students preferred the white doll, Clark concluded that segregated schools lowered the self-esteem of African American children.

Supreme Court Decision

In 1952, the Supreme Court heard the Briggs case. They sent it back to the district court for a new hearing. This was because Clarendon County school officials had sent a report about their progress in making facilities equal. In March, the district court heard the case again. The court found that some progress had been made toward equality. However, Thurgood Marshall argued that even if facilities were improved, schools would still be unequal as long as separation existed.

The case was appealed back to the Supreme Court in May. There, it was combined with several other school desegregation cases. These cases together became known as Brown v. Board of Education.

Briggs was the first of these five Brown cases to be argued before the Supreme Court. Spottswood Robinson and Thurgood Marshall argued for the plaintiffs. Former Solicitor General John W. Davis led the argument for the defense.

After the Brown decision, the lower court followed the Supreme Court's order. It declared South Carolina's school segregation law unconstitutional.

What Happened Next

Even though Brown was a legal victory against segregation, it was very difficult for those involved in Briggs. Reverend Joseph DeLaine, a leader in Summerton's African-American community, lost his job at a local school. His wife, Mattie, and all the other people who signed the petition also lost their jobs. Reverend DeLaine's church was burned down. He moved to Buffalo, New York in 1955 after someone tried to shoot him.

Harry and Eliza Briggs, whose children were named in the lawsuit, also lost their jobs. Harry worked in Florida for over ten years to support his family. Eliza eventually moved to New York to be with her children.

Judge Waring had already been treated badly by the white community in Charleston. This was because of his earlier decisions that supported equal rights. After his strong disagreement in the three-judge panel, he retired in 1952 and moved to New York.

Years later, the state of South Carolina honored Eliza Briggs with its highest civilian award, the Order of the Palmetto. Reverend Joseph A. De Laine, Harry and Eliza Briggs, and Levi Pearson were all given Congressional Gold Medals after their deaths in 2003.

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |