Franklin D. Roosevelt and civil rights facts for kids

Franklin D. Roosevelt was a very important president who led the United States during tough times like the Great Depression and World War II. His actions on civil rights were a mix of good and bad. Many African Americans, Catholics, and Jewish people liked him. However, he has been criticized for putting Japanese Americans in special camps during World War II. Also, a government agency he created, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), had rules that made it hard for people of color to get home loans in certain areas. These rules also tried to stop schools from mixing students of different races.

Contents

Mexican Repatriation

During the 1930s, a policy called the Mexican Repatriation forced many people of Mexican heritage to move to Mexico. This policy started before Roosevelt became president but continued during his time. Between 355,000 and one million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were sent to Mexico. A large number of these, about 40 to 60 percent, were actually U.S. citizens who were born in America, mostly children.

Most people left voluntarily, but some were formally deported. While the federal government supported this, local city and state governments often led the efforts. When Roosevelt became president, the number of people sent back to Mexico went down. He made policies that were kinder to Mexican immigrants, especially those who had lived in the U.S. for a long time. Some experts believe this policy was a harsh way of forcing Mexican Americans out of the country.

Fair Employment Order

In June 1941, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802. This order created the Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC). It was a very important step for the rights of African Americans between the Reconstruction period and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The order said that the government and companies working for the government could not refuse to hire someone because of their race, color, religion, or where they came from. The FEPC made sure this rule was followed. Because of this order, millions of African Americans and women got better jobs and better pay.

World War II brought the issue of race to the front. The U.S. Army had been separated by race since the Civil War, and the Navy since the early 1900s. By 1940, many African American voters had started supporting the Democratic Party. Leaders like Walter Francis White of the NAACP and T. Arnold Hill of the National Urban League became important allies for Roosevelt.

In June 1941, a leading African American workers' group leader named A. Philip Randolph pushed Roosevelt to sign the executive order. Even with the order, some parts of the military, especially the Navy and Marines, found ways to avoid it. The Marine Corps stayed all-white until 1942.

In September 1942, Roosevelt met with African American leaders. They asked for full integration in the military, meaning people of all races could serve in combat roles and in all branches. Roosevelt agreed, but he didn't make it happen. It was up to the next president, Harry S. Truman, to fully desegregate the armed forces.

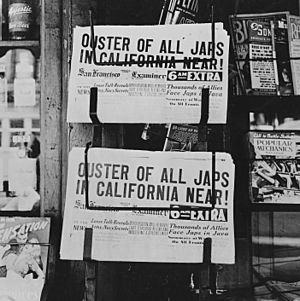

Japanese American Internment

After the Pacific War began, the military wanted all people of Japanese descent, including U.S. citizens, to be moved away from war zones on the West Coast. About 120,000 people of Japanese heritage lived in California. On February 11, 1942, Roosevelt met with his Secretary of War, who convinced him to approve a forced evacuation.

Roosevelt looked at secret information. He knew that Japanese people in the Philippines had helped the Japanese invasion troops. There was also evidence of spying from secret messages sent to Japan from agents in North America and Hawaii. These secret messages were only known by top officials like Roosevelt, so Japan wouldn't know their codes were broken.

On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order allowed the military to create special areas where certain people could be excluded. This led to the forced relocation and imprisonment of Japanese Americans in internment camps.

Roosevelt released the imprisoned Japanese Americans in 1944. On February 1, 1943, when he activated the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (a military unit mostly made of Japanese American citizens from Hawaii), he said: "No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry. The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry."

Interior Secretary Ickes tried to convince Roosevelt throughout 1944 to release the Japanese American prisoners. But Roosevelt waited until after the November 1944 presidential election. Fighting for Japanese American civil rights would have caused problems with powerful politicians and news groups, and it might have hurt his chances of winning California.

Critics believe Roosevelt's actions were partly due to racism. In 1925, he had written that Japanese immigrants could not easily fit into American society. He also wrote that mixing Asian and European/American blood often led to "unfortunate results." In 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court said that the executive order was legal in the Korematsu v. United States case. The order stayed in effect until December of that year.

The Holocaust and Jewish People

Jewish People Outside the U.S.

During his first term, Roosevelt spoke out against Hitler's persecution of German Jews. However, in the years leading up to the U.S. joining World War II, his government did not strongly protest on behalf of Jewish people facing increasing danger in Germany.

As more Jewish people fled Germany after 1937, American Jewish groups and politicians asked Roosevelt to let these refugees settle in the U.S. At first, he suggested that Jewish refugees should be "resettled" in other places like Venezuela or Ethiopia, anywhere but the U.S. Some of his advisors, like Henry Morgenthau and Eleanor Roosevelt, urged him to be more welcoming. But he was worried about angering people who used anti-Jewish feelings to attack his policies.

Even in 1944, when many Americans wanted to let more Jewish refugees in, Roosevelt prevented existing immigration limits from being filled by Jewish people. He also stopped plans to resettle Jewish refugees in the Dominican Republic and the United States Virgin Islands.

Very few Jewish refugees came to the U.S. Only 22,000 German refugees were allowed in 1940, and not all of them were Jewish. In 1939, the State Department under Roosevelt did not allow a ship called the St. Louis to enter the United States. This ship carried nearly a thousand German Jews fleeing from the Nazis. Roosevelt did not respond to their pleas for safety, and the ship was forced to return to Europe. Many of its passengers later died in concentration camps.

After 1942, Roosevelt learned more about the Nazi plan to kill Jewish people from leaders like Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise. He told them the best solution was to defeat Nazi Germany. In January 1944, a close advisor, Henry Morgenthau, convinced Roosevelt to create the War Refugee Board. This board helped more Jewish people enter the U.S. in 1944 and 1945. It also helped fund the work of Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg in Budapest, who saved over 100,000 Jewish people from death camps. However, by this time, most Jewish communities in Europe had already been destroyed in Hitler's Holocaust. The U.S. chose not to bomb Auschwitz or other concentration camps, even though some thought it could slow the killings.

After the Allies took control of North Africa in 1942, Roosevelt chose to keep leaders in power who were against Jewish people. Some Jewish people remained in concentration camps, and unfair laws against them stayed in place. Roosevelt privately argued that Jewish people didn't need the right to vote yet. He also thought there should be a limit on how many Jewish people could be in certain jobs. Only after many Jewish organizations in the U.S. protested did Roosevelt change his policy regarding North African Jews. Still, anti-Jewish laws remained for 10 months after the U.S. took control.

Attitudes to Jews in the U.S.

Roosevelt had many Jewish friends and advisors, like Felix Frankfurter and Bernard Baruch. He appointed Henry Morgenthau, Jr. as the first Jewish Secretary of the Treasury and appointed Frankfurter to the Supreme Court. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin noted that Roosevelt appointed many Jewish people to high-level positions (15% of his top appointments, even though Jewish people were only 3% of the U.S. population). This led to frequent criticism. Some newspapers and groups in the 1930s and 1940s called his New Deal policies the "Jew Deal" and claimed Jewish people controlled the American government.

However, Roosevelt also sometimes showed negative attitudes towards Jewish people in private and public. As a leader at Harvard University in 1923, he helped set a limit on the number of Jewish students allowed. According to historian Rafael Medoff, Roosevelt's negative comments about Jewish people often suggested that having too many Jewish people in one job or place was not good. He also believed America should remain mostly white and Protestant, and that Jewish people had certain negative traits.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |