Felix Frankfurter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Felix Frankfurter

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office January 30, 1939 – August 28, 1962 |

|

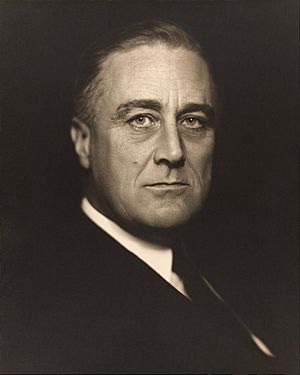

| Nominated by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Cardozo |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Goldberg |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 15, 1882 Vienna, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | February 22, 1965 (aged 82) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Spouse |

Marion Denman

(m. 1919) |

| Education | City College of New York (AB) Harvard University (LLB) |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (1963) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1918 |

| Rank | Major |

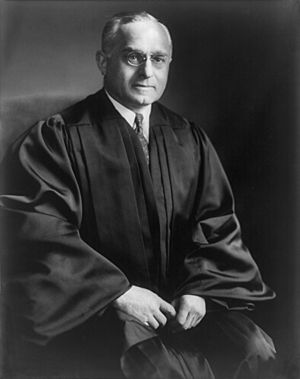

Felix Frankfurter (born November 15, 1882 – died February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American legal expert and judge. He served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 to 1962. During his time on the Court, he was known for believing that judges should not make new laws, but instead follow the laws made by elected officials. This idea is called judicial restraint.

Frankfurter was born in Vienna, Austria. When he was 12, his family moved to New York City. He later graduated from Harvard Law School. He worked for Henry L. Stimson, who was the U.S. Secretary of War. During World War I, Frankfurter worked as a military lawyer. After the war, he helped start the American Civil Liberties Union, which works to protect people's rights. He then returned to teach at Harvard Law School. He became a close friend and advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who later chose him to join the Supreme Court.

Frankfurter served on the Supreme Court until he retired in 1962. He wrote important opinions for the Court in cases like Minersville School District v. Gobitis and Gomillion v. Lightfoot. He also wrote dissenting opinions, meaning he disagreed with the majority, in cases such as Baker v. Carr and West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Felix Frankfurter was born on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, which was then part of Austria-Hungary. He came from a Jewish family. His father, Leopold Frankfurter, was a merchant. In 1894, when Felix was twelve, his family moved to the United States. They settled in the Lower East Side of New York City, an area where many immigrants lived.

Frankfurter went to public schools in New York City, including Townsend Harris High School. He was a very good student and enjoyed playing chess. He spent a lot of time reading at Cooper Union and listening to talks about topics like worker's rights and socialism.

In 1902, he graduated from City College of New York. To earn money for law school, he worked for the Tenement House Department in New York City. He then got into Harvard Law School, where he did very well. He became an editor for the Harvard Law Review and graduated at the top of his class.

Starting His Career

Frankfurter began his legal career in 1906 at a law firm in New York. That same year, he became an assistant to Henry Stimson, who was the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. Frankfurter was interested in progressive ideas, which aimed to improve society and government.

In 1911, President William Howard Taft made Stimson his Secretary of War. Stimson then appointed Frankfurter to work for him in the government. Frankfurter supported Theodore Roosevelt's ideas for a "New Nationalism," which focused on government playing a bigger role in regulating business and protecting workers.

World War I Service

When the United States joined World War I in 1917, Frankfurter took a break from Harvard. He became a special assistant to the Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker. He was also appointed as a Judge Advocate General, which meant he oversaw military court cases for the War Department.

In 1917, President Wilson asked Frankfurter to help solve major strikes that were affecting war production. He looked into different labor issues and saw how difficult conditions could lead to bigger problems. His work made some people see him as a supporter of radical ideas, but he believed in addressing social problems to prevent unrest.

After the War

After World War I, Frankfurter became more involved in Zionism, a movement supporting a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He worked with Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis to encourage President Wilson to support the Balfour Declaration, which was a British statement supporting this idea.

Marriage

In 1919, Felix Frankfurter married Marion Denman. She was a graduate of Smith College. They did not have any children.

Helping to Found the ACLU

Frankfurter continued to be active in public life. In 1920, he helped create the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). The ACLU works to protect the rights and freedoms of all Americans. During a time when many suspected communists were being arrested, Frankfurter and other lawyers spoke out against illegal actions by the government. They argued that people's rights were being violated.

In the late 1920s, Frankfurter gained public attention when he supported calls for a new trial for Sacco and Vanzetti. These two Italian immigrants had been sentenced to death for robbery and murder. Frankfurter wrote a book and articles arguing that their convictions might have been unfair due to prejudice against immigrants and fear of radical ideas.

Advisor to President Roosevelt

After Franklin D. Roosevelt became president in 1933, Frankfurter quickly became one of his trusted advisors. Frankfurter was known for his liberal views and supported new laws to help the country. He believed that major changes were needed to deal with the economic problems of the Great Depression.

Frankfurter suggested many talented young lawyers for government jobs in Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs. These lawyers became known as "Felix's Happy Hot Dogs." Some of them included Thomas Gardiner Corcoran, Donald Hiss, Alger Hiss, and Benjamin Victor Cohen. Even though he advised the president, Frankfurter still felt like an outsider in Washington, D.C. He turned down offers to become a judge in Massachusetts and the Solicitor General of the United States.

Some of the "Frankfurter men" who worked in the New Deal included:

- Dean Acheson, who worked for the Treasury Department.

- Thomas Gardiner Corcoran, who worked for the Public Works Administration.

- James M. Landis, who led the Securities and Exchange Commission.

- Alger Hiss, who worked for the Justice Department.

- Paul Freund, also at the Justice Department.

- Benjamin V. Cohen, who worked for the Public Works Administration.

- Jerome Frank, who worked for the Reconstruction Finance Corporation.

- Charles Wyzanski, who worked for the Labor Department.

- Thomas Elliott, who was a lawyer for the new social security organization.

Supreme Court Justice

In 1938, a Supreme Court justice named Benjamin N. Cardozo passed away. President Roosevelt asked Frankfurter for ideas on who should fill the spot. But Roosevelt decided to nominate Frankfurter himself. Frankfurter's nomination was controversial. Some people opposed him because he was foreign-born and had been linked to groups they considered too radical.

Frankfurter was asked to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions. He was only the second Supreme Court nominee ever to testify in a hearing. On January 17, 1939, the U.S. Senate confirmed his nomination.

Frankfurter served on the Supreme Court from January 30, 1939, to August 28, 1962. He wrote many opinions for the Court. He was a strong supporter of judicial restraint. This idea means that courts should not use the Constitution to limit the power of the legislative (law-making) and executive (law-enforcing) branches of government too much. He believed that judges should not make policy decisions, but rather stick to interpreting the law as it is written.

One example of his judicial restraint philosophy was in the 1940 case Minersville School District v. Gobitis. This case involved Jehovah's Witness students who were expelled from school for not saluting the flag. Frankfurter wrote the Court's opinion, saying that schools could require students to salute the flag. He believed that religious beliefs should not excuse citizens from their civic duties and that allowing exceptions might reduce loyalty to the nation. However, this decision led to attacks on Jehovah's Witnesses. The Court later overturned this decision in 1943 in the case West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette.

In the case Baker v. Carr, Frankfurter believed that federal courts should not get involved in how states draw their voting districts. He thought this was a political issue that the Supreme Court should avoid. However, the majority of the justices disagreed and ruled that federal judges could indeed get involved in such matters.

Frankfurter also believed that the Supreme Court's authority would be weakened if it went too strongly against public opinion. He tried to avoid unpopular decisions.

In 1960, Frankfurter turned down Ruth Bader Ginsburg for a clerkship position because she was a woman. She later became an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court herself and was the first Jewish woman to serve on the Court.

Frankfurter's seat on the Supreme Court later became known informally as the "Jewish seat." This is because four Jewish justices held it one after another between 1932 and 1969: Cardozo, Frankfurter, Goldberg, and Fortas.

Relationships with Other Justices

Frankfurter tried to influence many new justices who joined the Court. He often disagreed with more liberal justices like Hugo Black and William O. Douglas. He felt their decisions were sometimes based on what they wanted the outcome to be, rather than strictly on the law.

Frankfurter's way of arguing was not always popular with his colleagues. Chief Justice Earl Warren once said, "All Frankfurter does is talk, talk, talk. He drives you crazy." Despite this, Frankfurter had a strong influence on some justices, like Robert H. Jackson.

Retirement and Death

Felix Frankfurter retired from the Supreme Court in 1962 after he had a stroke. He was replaced by Arthur Goldberg. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is a very high honor for civilians.

Felix Frankfurter passed away in 1965 at the age of 82 from heart failure. He is buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Legacy

Frankfurter's important papers and writings are kept at the Library of Congress and Harvard University. These collections are open for people to study.

A chapter of the Jewish youth organization Aleph Zadik Aleph in Arizona is named in his honor. Also, a chapter of the legal organization Phi Alpha Delta at Suffolk University in Boston is named after him.

Works

Felix Frankfurter wrote several books during his career. Some of his well-known works include:

- Cases Under the Interstate Commerce Act

- The Business of the Supreme Court (1927)

- Mr. Justice Holmes and the Supreme Court (1938)

- The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927)

- Felix Frankfurter Reminisces (1960)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Felix Frankfurter para niños

In Spanish: Felix Frankfurter para niños

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2)

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Stone Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Vinson Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |