Hugo Black facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hugo Black

|

|

|---|---|

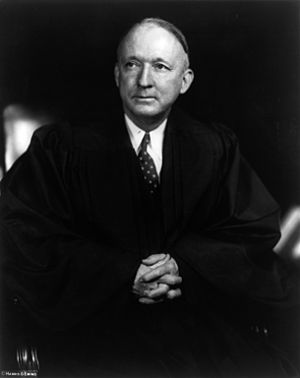

Black photographed by Harris & Ewing, 1937

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office August 19, 1937 – September 17, 1971 |

|

| Nominated by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Willis Van Devanter |

| Succeeded by | Lewis F. Powell Jr. |

| Chair of the Senate Education Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1937 – August 19, 1937 |

|

| Preceded by | David Walsh |

| Succeeded by | Elbert Thomas |

| Secretary of the Senate Democratic Conference | |

| In office 1927–1937 |

|

| Leader | Joseph Taylor Robinson |

| Preceded by | William H. King |

| Succeeded by | Joshua B. Lee |

| United States Senator from Alabama |

|

| In office March 4, 1927 – August 19, 1937 |

|

| Preceded by | Oscar Underwood |

| Succeeded by | Dixie Graves |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hugo Lafayette Black

February 27, 1886 Harlan, Alabama, U.S. |

| Died | September 25, 1971 (aged 85) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

Josephine Foster

(m. 1921; died 1951)Elizabeth DeMeritte

(m. 1957) |

| Children | 3, including Hugo and Sterling |

| Education | University of Alabama (LLB) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 81st Field Artillery Regiment |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Hugo Lafayette Black (born February 27, 1886 – died September 25, 1971) was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a U.S. Senator for Alabama from 1927 to 1937. Later, he became an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1937 to 1971.

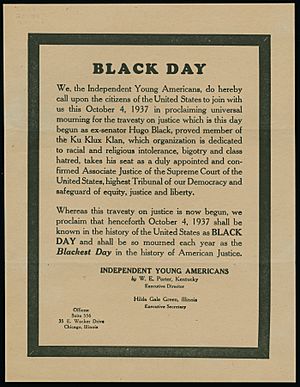

Black was a member of the Democratic Party. He strongly supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal programs. Before becoming a Senator, Black was briefly a member of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama. He resigned from the group in 1925. When he was appointed to the Supreme Court, Black stated he had left the Klan and had no connection to it since.

He was one of the most important Supreme Court justices in the 1900s. Black believed in reading the U.S. Constitution very closely, sticking to its exact words. He also thought that the rights listed in the Bill of Rights should apply to all states through the Fourteenth Amendment. He was famous for saying "No law [abridging the freedom of speech] means no law" when talking about the First Amendment. Black helped expand individual rights in cases like Gideon v. Wainwright and Engel v. Vitale.

However, some of Black's views were not always seen as liberal. During World War II, he supported the government's decision to put Japanese Americans in special camps. Later in his career, he became more conservative on some issues. For example, he did not believe the Constitution created a right to privacy, voting against it in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965).

Contents

Early Life and Career

Hugo Black was born in Harlan, Alabama, on February 27, 1886. He was the youngest of eight children. In 1890, his family moved to Ashland, Alabama.

Black went to Ashland College and then studied law at the University of Alabama School of Law. He finished his law degree in 1906 and started practicing law in Ashland. In 1907, he moved to Birmingham, a growing city. There, he became a successful lawyer, often working on cases about workers' rights and personal injuries.

In 1911, Black became a police court judge for a short time. This was his only experience as a judge before joining the Supreme Court. He resigned in 1912 to go back to being a full-time lawyer. In 1914, he became the Jefferson County Prosecuting Attorney for four years.

During World War I, Black joined the United States Army. He served in the 81st Field Artillery Regiment and became a captain. The war ended before his unit went to Europe, so he returned to his law practice.

In the early 1920s, Black joined a local group of the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham. He resigned from the group in 1925. In 1937, after he was confirmed to the Supreme Court, news came out that he had received a "grand passport" from the Klan in 1926, which meant he was a member for life. Black said he never used this passport and had not kept it. He stated that he had completely stopped all ties with the Klan when he resigned and never planned to rejoin.

On February 23, 1921, he married Josephine Foster. They had three children: Hugo L. Black, II, Sterling Foster, and Martha Josephine. Josephine passed away in 1951. In 1957, Black married Elizabeth Seay DeMeritte.

Becoming a Senator

In 1926, Black ran for the United States Senate in Alabama. He easily won the election because the Democratic Party was very strong in Alabama at that time. He was reelected in 1932.

As a Senator, Black became known as a tough investigator. In 1934, he led a committee that looked into problems with contracts for air mail carriers. This investigation led to new laws about air mail. He also investigated lobbying practices, where people try to influence lawmakers. He wanted laws that would make lobbyists publicly register their names and how much they were paid.

During the Great Depression in 1935, Black became the chairman of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor. He used this position to fight for new laws. He spoke on national radio about how big electric companies tried to stop a bill that would control them.

In 1937, he supported a bill that aimed to create a national minimum wage and limit the workweek to thirty hours. This bill, later changed to a forty-four-hour workweek, became the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. This law helped many workers.

Black was a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs. He especially supported Roosevelt's plan to add more justices to the Supreme Court, which was known as the "court-packing bill." Black believed the Supreme Court was wrongly stopping laws passed by Congress.

Throughout his time as a senator, Black opposed laws against lynching, which were violent acts against African Americans. He joined other Southern Democrats in blocking these bills.

Joining the Supreme Court

After his "court-packing" plan failed, President Roosevelt got his first chance to appoint a new Supreme Court justice. He wanted someone young who strongly supported the New Deal and came from a part of the country not yet represented on the Court. Hugo Black was chosen because he had voted for all of Roosevelt's major New Deal programs as a senator.

On August 12, 1937, Roosevelt nominated Black. Usually, a senator nominated for a position is quickly confirmed. But this time, the nomination was sent to a committee. Black was criticized because of his past connection to the Ku Klux Klan. However, Black was friends with Walter Francis White, a leader of the NAACP, who helped calm some of the concerns. Black's later rulings, like in Chambers v. Florida (1940), where he supported African American defendants, also helped ease these worries.

The Senate confirmed Black's appointment on August 17, 1937, by a vote of 63 to 16. He officially started his job on August 19, 1937. Soon after, his Klan membership became widely known, causing public outrage. Despite this, Black became a strong supporter of civil liberties and civil rights during his time on the Court.

His Time on the Supreme Court

When Black joined the Supreme Court, he wanted the Court to avoid getting too involved in social and economic issues. He believed in the "plain meaning" of the Constitution's words and that the legislature (Congress) should have the most power. For Black, the Supreme Court's role was limited to what the Constitution clearly said.

In his early years on the Court, Black helped overturn earlier decisions that had limited federal power. This allowed many New Deal laws to be upheld. From 1945 until 1971, Black was the longest-serving associate justice on the Supreme Court.

Protecting Rights and the Constitution

Black's way of interpreting the law was very unique. He focused on three main ideas: history, literalism, and absolutism. He believed studying history helped prevent past mistakes.

His commitment to literalism meant he used the exact words of the Constitution to limit the power of judges. He thought judges should support the laws made by Congress, unless those laws clearly took away people's freedoms. Black often reminded his fellow justices that they must stay within the Constitution's limits.

Third, Black's absolutism meant he strongly enforced the rights in the Constitution. He did not try to limit or define the scope of each right. He believed the Bill of Rights should be fully applied.

Black strongly believed in judicial restraint. This means judges should not create new laws or policies. Instead, they should let the elected lawmakers in Congress do that. He often criticized other judges who he felt were making laws from the bench. Black thought the Constitution could only be changed by the amendment process, not by judges.

Free Speech and Religion

Black took a very strict view of the First Amendment, which says "Congress shall make no law..." He believed this meant no law at all could limit free speech. He did not agree with ideas that allowed speech to be limited for reasons like "national security." For example, in the New York Times Co. v. United States case (1971), he voted to allow newspapers to publish the Pentagon Papers. He said the press must be free to expose government secrets.

He also believed in a strict separation of church and state. He wrote important opinions saying that the government could not provide religious teaching in public schools (McCollum v. Board of Education, 1948) or require official prayers in public schools (Engel v. Vitale, 1962). He also said states could not require religious tests for public office (Torcaso v. Watkins, 1961).

However, Black did not believe that all actions were "speech." For him, "conduct" did not get the same protection as "speech." For example, he did not think flag burning was protected speech. He also believed people did not have the right to speak wherever they wanted.

Rights for All States

One of Black's most important ideas was that the entire Bill of Rights should apply to the states, not just the federal government. Originally, the Bill of Rights only limited the federal government. Black argued that the Fourteenth Amendment, passed in 1868, "incorporated" these rights, making them binding on the states too. He pointed to the "Privileges or Immunities Clause" in the Fourteenth Amendment.

While the Supreme Court never fully accepted Black's idea of "total incorporation," it did agree that many "fundamental" rights from the Bill of Rights should apply to the states. Over time, especially in the 1960s, the Court made almost all the rights in the Bill of Rights apply to the states. This result was very close to what Black had wanted.

Black also strongly disagreed with the idea of "substantive due process." This idea suggests that the "due process" clause in the Constitution protects certain "fundamental rights" even if they are not explicitly written. Black believed this gave judges too much power to make up new rights. He thought "due process" simply meant the government must follow existing laws and the written Constitution.

Voting Rights

Black was a strong supporter of the "one man, one vote" principle. This means that everyone's vote should count equally. He wrote the Court's opinion in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964), which said that congressional districts in any state must have roughly equal populations. He believed the Constitution meant "one man's vote in a congressional election is to be worth as much as another's." He also supported applying this idea to state legislative districts.

However, Black did not believe that poll taxes were unconstitutional. Poll taxes were fees people had to pay to vote, which often prevented poorer people, especially African Americans, from voting. He disagreed when the Court later ruled that poll taxes were unconstitutional. He felt the Court was creating new meanings for the Constitution instead of interpreting its original meaning.

Equal Protection

By the late 1940s, Black believed that the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause stopped states from discriminating based on race. He was part of the unanimous decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which said that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Black wanted to end segregation quickly in the South.

However, Black also wrote the Court's opinion in Korematsu v. United States (1944), which upheld the government's decision to put Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II. This decision showed his belief that the judiciary should have a limited role and respect actions taken by the legislative and executive branches during wartime.

Black also tended to favor "law and order" over some forms of civil rights protests. He believed that actions like protesting, singing, or marching should be regulated by laws. He thought that legislatures, and then courts, should fix social problems, not protesters.

Retirement and Death

Justice Black became ill and retired from the Supreme Court on September 17, 1971. He passed away eight days later, on September 25, 1971.

His funeral was held at the Washington National Cathedral. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery, a place where many important Americans are laid to rest. He is one of fourteen Supreme Court justices buried there.

President Richard Nixon chose Lewis Powell to take Black's place on the Supreme Court.

Ku Klux Klan and Anti-Catholicism

After Black was appointed to the Supreme Court, a newspaper reporter named Ray Sprigle wrote articles revealing Black's past involvement with the Ku Klux Klan. Sprigle suggested that Black's resignation from the Klan was a political move to help him get elected to the Senate.

President Roosevelt said he did not know about Black's Klan membership.

On October 1, 1937, Black spoke on the radio to address the public. He said, "I did join the Klan. I later resigned. I never rejoined." He also stated that he had many friends who were African American and that they deserved full protection under the Constitution. Near the end of his life, Black admitted that joining the Klan was a mistake, saying he would have joined any group that helped him get votes.

Some historians have noted that Black had anti-Catholic views in his early career and gave speeches to Klan meetings during his 1926 election campaign. However, later in his career, he appointed a Jewish law clerk and a Catholic secretary, showing a change in his views.

Thurgood Marshall and Brown v. Board of Education

Hugo Black was one of the nine Supreme Court justices who made the historic decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. This unanimous ruling declared that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The lawyers representing the plaintiffs in this case included Thurgood Marshall.

A decade later, on October 2, 1967, Thurgood Marshall became the first African American to be appointed to the Supreme Court. He served alongside Hugo Black until Black's retirement in 1971.

United States v. Price

In the case of United States v. Price (1965), eighteen members of the Ku Klux Klan were accused of murder and conspiracy in the deaths of three civil rights workers: James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. The initial charges were dismissed by a lower court. However, a unanimous Supreme Court, including Justice Black, reversed this dismissal. They ordered the case to go to trial. As a result, seven of the Klansmen were found guilty of the crime.

Legacy

Hugo Black was featured on the cover of Time magazine twice. In 1986, he appeared on a 5¢ postage stamp issued by the United States Postal Service.

In 1987, a new courthouse building in Birmingham, Alabama, was named the "Hugo L. Black United States Courthouse" in his honor.

A large collection of Black's personal and official papers is kept at the Library of Congress. The University of Alabama School of Law also has a special collection honoring Justice Black.

Black served on the Supreme Court for thirty-four years, making him the fifth longest-serving Justice in the Court's history. He was the senior (longest-serving) justice on the Court for twenty-five years, which is a very long time.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hugo Black para niños

In Spanish: Hugo Black para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |