Michael Schwerner facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Schwerner

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Michael Henry Schwerner

November 6, 1939 |

| Died | June 21, 1964 (aged 24) |

| Other names | Mickey Schwerner |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Awards | Presidential Medal of Freedom (Posthumous; 2014) |

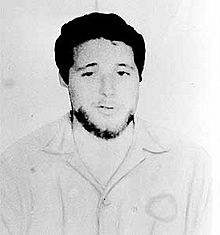

Michael Henry Schwerner (born November 6, 1939 – died June 21, 1964) was a brave young man. He was one of three civil rights workers who were killed in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Members of the Ku Klux Klan murdered them. This happened because of their important work for civil rights. They helped African Americans register to vote. Many African Americans in Mississippi could not vote at that time.

Contents

Michael Schwerner's Early Life

Michael Schwerner was born on November 6, 1939. His family was Jewish. He grew up in Pelham, New York. His friends called him Mickey. His mother, Anne Siegel, was a science teacher. His father, Nathan Schwerner, was a businessman.

Mickey first went to Michigan State University. He wanted to be a veterinarian. Later, he moved to Cornell University. There, he studied rural sociology. He also joined a fraternity called Alpha Epsilon Pi. After Cornell, he went to Columbia University. He studied social work there.

When he was a boy, Mickey became friends with Robert Reich. Robert Reich later became a U.S. Secretary of Labor. Mickey helped protect Robert from bullies.

Working for Civil Rights

In the early 1960s, Michael Schwerner became very active in the Civil Rights Movement. He worked to gain equal rights for African Americans. He led a group called "Downtown CORE" in New York City. CORE stands for the Congress of Racial Equality.

In 1963, he helped to end segregation at Gwynn Oak Amusement Park in Maryland. Segregation meant that Black and White people were kept separate.

Mickey and his wife, Rita Schwerner Bender, decided to help in Mississippi. They volunteered for National CORE. They worked with leaders like Dave Dennis and Bob Moses. The Schwerners were the first white CORE workers assigned outside of Jackson. They helped set up a community center in Meridian. There, they met James Chaney, a local young man who joined their work.

In the summer of 1964, CORE started "Freedom Summer." This project aimed to teach and register African Americans to vote. Many young people, including college students, came to Mississippi to help.

White people in Mississippi often did not like civil rights activists. A state agency called the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission spied on activists. They also tried to stop their work using boycotts and threats.

The Ku Klux Klan especially targeted Michael Schwerner. He and Rita ran the Meridian CORE office. They created a community center for Black people. Mickey tried to talk to white working-class people in Meridian. He also organized a boycott of a store. The store did not hire Black workers. Mickey believed in "don't shop where you can't work."

The Tragic Deaths

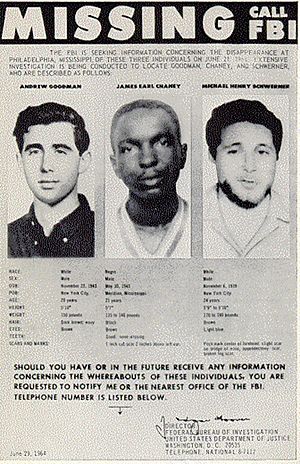

On June 21, 1964, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman were killed. They were near Philadelphia, Mississippi. They had been investigating a church burning. The church, Mt. Zion Methodist, was a Freedom School site.

Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price arrested the three men. He said they had a traffic violation. He took them to jail in Neshoba County. They were let go that evening. They were not allowed to call anyone. On their way back to Meridian, KKK members stopped them. The KKK members took them to a remote road and killed them.

The disappearance of the civil rights workers became a huge national news story. The federal government quickly started a large investigation. The FBI and U.S. Navy sailors helped search for them.

Justice for the Killings

The U.S. government brought charges against those involved. Seven men, including Deputy Sheriff Price, were found guilty. Some other defendants were not convicted.

Years later, the case was reopened. Journalist Jerry Mitchell found new evidence. He also found new witnesses. A high school teacher, Barry Bradford, and his students helped too. Their project for National History Day showed important new information. Barry Bradford even interviewed Edgar Ray Killen. This helped convince the state to look at the case again.

On June 21, 2005, Edgar Ray Killen was found guilty. He was known as "Preacher" and believed in white supremacy. He was found guilty of three counts of manslaughter. He was sentenced to sixty years in prison.

Michael Schwerner's Character

Friends and family described Michael Schwerner as a friendly person. They said he was good-natured and gentle. He was also mischievous and "full of life and ideas." He believed that all people were good. He loved sports, animals, and rock music.

Robert Reich said that Michael Schwerner inspired him. Robert was bullied as a child. Mickey helped protect him. This made Robert want to "fight the bullies." He wanted to "protect the powerless" and "make sure that the people without a voice have a voice."

Honoring Michael Schwerner

Schwerner's Legacy

- In 2008, his hometown of Pelham, New York, honored him. A part of Harmon Avenue was renamed "Michael Schwerner Way."

- In 2014, Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney received a special award. President Barack Obama gave them the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This was given after their deaths.

See also