Alger Hiss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

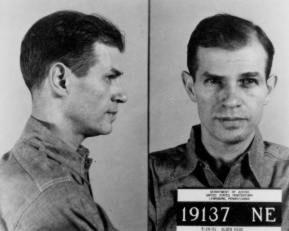

Alger Hiss

|

|

|---|---|

Hiss testifying in 1948

|

|

| Born | November 11, 1904 |

| Died | November 15, 1996 (aged 92) New York City, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Being accused of espionage |

| Criminal charge(s) | 2 counts of perjury |

| Criminal penalty | 2 concurrent terms of 5 years in prison |

| Criminal status | Released after 3 years and 8 months |

| Spouse(s) |

Priscilla Hiss

(m. 1929; died 1984)Isabel Johnson

(m. 1985) |

| Relatives |

|

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government worker. In 1948, he was accused of being a spy for the Soviet Union during the 1930s. The time limit for charging someone with espionage (spying) had passed. However, Hiss was found guilty of perjury in 1950. Perjury means lying under oath in court.

Before his trial, Hiss helped set up the United Nations. He worked for both the U.S. State Department and the UN. Later in life, he became a speaker and writer.

On August 3, 1948, a former Communist Party member named Whittaker Chambers told the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that Hiss was secretly a communist. Hiss strongly denied this and sued Chambers for libel (spreading false and damaging statements). During the legal process, Chambers showed new evidence. This evidence suggested that he and Hiss were involved in spying. A special jury, called a grand jury, then charged Hiss with two counts of perjury.

After one trial ended without a decision, Hiss was tried again. In January 1950, he was found guilty. He was sentenced to two five-year prison terms, which he served at the same time. He spent three and a half years in prison. The case became a big part of discussions about the Cold War and McCarthyism. This was a time when many Americans worried about communism. Hiss always said he was innocent until he died in 1996.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

Early Life and Education

Alger Hiss was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on November 11, 1904. He was one of five children. His parents came from well-known families in Baltimore. Hiss's father died when Alger was only two years old.

Even though his childhood had some sadness, Hiss enjoyed playing with his siblings and cousins. He described his family's financial situation as "modest." Later, two more of his older siblings passed away.

Hiss was a popular and smart student. He went to Baltimore City College for high school. Then he attended Johns Hopkins University, where his classmates voted him "most popular." He graduated with high honors. In 1929, he earned his law degree from Harvard Law School. There, he was a student of Felix Frankfurter, who later became a U.S. Supreme Court justice.

After law school, Hiss worked for a year as a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.. He then joined law firms in Boston and New York City.

Government Career

During President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal era, Hiss became a government lawyer. In 1933, he worked briefly at the Justice Department. He then helped the Senate's Nye Committee. This committee looked into high costs and unfair profits by military companies during World War I.

In 1936, Alger Hiss and his brother Donald Hiss began working for the State Department. Alger held several positions, including assistant to the director of Far Eastern Affairs.

In 1944, Hiss became the Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs. This office planned for international groups after the war. Hiss was a key organizer for the Dumbarton Oaks Conference. This meeting helped create the first plans for the United Nations.

In February 1945, Hiss was part of the U.S. team at the Yalta Conference. Here, leaders from the U.S., Soviet Union, and Britain met. They discussed how to end World War II and plan for Europe's future. Hiss helped prepare documents for this important meeting. He also worked on the "Declaration of Liberated Europe," which concerned Eastern Europe's future.

Hiss also helped decide how many votes each country would get in the United Nations General Assembly. He argued against the Soviet Union's idea to have many votes. In the end, the Soviets received three votes.

Hiss was the Secretary-General for the conference that created the UN Charter. This meeting took place in San Francisco in 1945. Later, Hiss left government work. He became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in 1946. He stayed in this role until 1949, when he had to step down.

Accusations of Spying

On August 3, 1948, Whittaker Chambers, a former Communist Party member, spoke to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He accused Alger Hiss of being a secret communist. Chambers said Hiss was part of a group that aimed to put communists into the U.S. government. He also claimed this group eventually aimed for espionage.

Congressman Richard Nixon was a key member of HUAC. He pushed hard to investigate Hiss. Rumors about Hiss had been around since 1939. Chambers had told government officials that Hiss was part of a secret communist group. The FBI also received similar information from other sources. The FBI began watching Hiss and his wife.

Hiss denied the accusations and agreed to speak to HUAC. He said he had never been a communist and didn't know Chambers. However, when shown a photo, Hiss admitted he might know Chambers. When they met in person, Hiss said he knew Chambers as "George Crosley," a freelance writer. Hiss claimed he had rented his apartment and given an old car to this "Crosley."

Chambers denied using the name Crosley. During a HUAC meeting, Chambers directly told Hiss, "I was a Communist and you were a Communist." Hiss then sued Chambers for libel.

To fight the lawsuit, Chambers claimed Hiss was not just a communist, but a spy. On November 17, 1948, Chambers showed physical evidence. This included 65 pages of re-typed State Department documents and four notes in Hiss's handwriting. Chambers said Hiss gave him these in 1938. He claimed Hiss's wife had retyped them for him to pass to the Soviets. These documents became known as the "Baltimore documents."

On December 2, Chambers led HUAC investigators to his farm. From a hollowed-out pumpkin, he pulled out five rolls of film. He said these also came from Hiss in 1938. Some film showed classified State Department documents. This dramatic event led to the film and documents being called the "Pumpkin Papers."

Perjury Trials and Conviction

A grand jury charged Hiss with two counts of perjury (lying under oath). He could not be charged with spying because the time limit for that crime had passed. Hiss had two trials. The first trial began in May 1949 and ended in July with no decision. Chambers admitted he had lied under oath before. Many important people, including future presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson II, spoke in support of Hiss.

The second trial lasted from November 1949 to January 1950. A key part of the prosecution's case was expert testimony. They said the typed "Baltimore documents" matched samples typed on a typewriter owned by the Hisses. The prosecution also showed the typewriter itself as evidence.

In the second trial, Hede Massing, a confessed Soviet spy, testified. She said she met Hiss at a party in 1935. She also claimed Hiss tried to recruit another spy, Noel Field, to his own spy group.

This time, the jury found Hiss guilty. Hiss continued to say he was innocent. He claimed the typewriter evidence was faked. On January 25, 1950, Hiss was sentenced to five years in prison.

The case made many people worry about Soviet spies in the U.S. government. Alger Hiss was a well-educated official from an old American family. He did not fit the usual idea of a spy. The case also brought Richard Nixon into the public eye. It helped him become a U.S. Senator, then Vice President, and later President. Senator Joseph McCarthy also gained fame as a strong anti-communist after the Hiss verdict.

Time in Prison

On March 22, 1951, Alger Hiss went to a federal prison. He was sentenced to five years but served three years and eight months. He was released on November 27, 1954. While in prison, Hiss helped other inmates as a volunteer lawyer and tutor.

After Prison

After his release in 1954, Hiss was no longer allowed to practice law. He worked as a salesman for a stationery company. In 1957, he wrote a book called In the Court of Public Opinion. In it, he challenged the case against him and said the typed documents were faked.

Hiss separated from his first wife, Priscilla, in 1959. She passed away in 1984. In 1985, he married Isabel Johnson.

In 1975, copies of the "pumpkin papers" were released to the public. These were the film rolls Chambers had hidden. Some film was blank or showed non-secret Navy documents. The rest were photos of the State Department documents used in Hiss's trials. A few days after this, Hiss was allowed to practice law again in Massachusetts. He was the first lawyer to be readmitted after a major criminal conviction.

In 1988, Hiss wrote his autobiography, Recollections of a Life. He continued to say he was innocent. He fought his conviction until his death on November 15, 1996, at age 92. His friends and family still believe he was innocent.

Personal Life

In 1929, Hiss married Priscilla Fansler Hobson. She was a teacher and had a young son, Timothy. Hiss and Priscilla also had a son, Tony Hiss. They separated in 1959.

Later, Hiss met Isabel (Dowden) Johnson, a writer and editor. After Priscilla's death in 1984, Hiss and Isabel married in 1986. Hiss was a member of the Episcopal Church.

In 1947, Johns Hopkins University gave Hiss an honorary law degree.

Later Evidence and Debates

The debate about Alger Hiss's guilt or innocence continued for many years. New information and opinions came out over time.

Typewriter Forgery Idea

During Hiss's trials, experts said the "Baltimore documents" matched typing from the Hisses' home typewriter. The defense team found the typewriter and brought it to court. It matched the documents, which seemed to prove Hiss's guilt.

After Hiss went to prison, his lawyer tried to get a new trial. He wanted to show that the typewriter evidence could have been faked. He hired an expert to create a typewriter that would type exactly like the Hisses' machine. This showed that faking such evidence was possible.

FBI documents released later showed that the FBI itself had doubts about the typewriter used in the trial. They wondered if it was truly Hiss's old machine. Hiss's lawyers argued that the FBI had hidden important information. They also claimed the FBI had an informer on Hiss's defense team.

Some people, including former White House counsel John Dean, claimed that President Nixon admitted that HUAC had "built" a typewriter for the Hiss case. Nixon denied this. The debate over the typewriter continued, with strong arguments on both sides.

Noel Field's Testimony

In 1992, records from Hungary were found. In these, a self-confessed Soviet spy named Noel Field mentioned Alger Hiss as a fellow agent. Field had been imprisoned and tortured by Soviet security services. He later said that the torture made him "confess more and more lies as truth." Hiss's supporters argued that Field's statements about Hiss might have been among those lies.

Venona and "ALES"

In 1995, the CIA and NSA revealed the existence of the Venona project. This project had secretly decoded thousands of Soviet telegrams from 1940 to 1948. One telegram, Venona #1822, mentioned a Soviet spy with the codename "ALES." This spy worked with a group of "Neighbors" (another Soviet intelligence group). FBI Special Agent Robert J. Lamphere believed "ALES" was "probably Alger Hiss."

Many historians, like Harvey Klehr and John Earl Haynes, strongly believe the Venona evidence proves Hiss was a Soviet spy. They point out that Venona #1822 seems to show that ALES attended the Yalta Conference and then went to Moscow, just as Hiss did.

However, others question if Venona #1822 is definite proof. Hiss's lawyer, John Lowenthal, argued that ALES was described as a military intelligence agent, while Hiss was accused of passing non-military State Department documents. Also, he argued that if Hiss was a spy, his real name would not have been used in a coded message.

Soviet Archives

After the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, Alger Hiss asked for any Soviet files on his case to be released. Russian archivists reported in 1992 that they found no evidence Hiss spied for the Soviet Union or was a Communist Party member. However, the general in charge later said he only spent two days on the search.

In 2009, Haynes, Klehr, and Alexander Vassiliev published a book called Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America. This book was based on notes Vassiliev, a former KGB agent, copied from KGB documents. The authors claimed these documents proved Hiss was a Soviet spy, using codenames like "ALES," "Jurist," and "Leonard." They said the documents left no doubt about his guilt.

Other historians disagreed, saying the book's conclusions were not fully supported by the evidence. They questioned how Vassiliev got his notes and if he might have left out important facts. The debate about Hiss's guilt continues, with different historians interpreting the evidence in different ways.

See Also

In Spanish: Alger Hiss para niños

In Spanish: Alger Hiss para niños

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2)

- Priscilla Hiss

- Donald Hiss

- John Abt

- Elizabeth Bentley

- Whittaker Chambers

- Noel Field

- Harold Glasser

- John Herrmann

- Victor Perlo

- J. Peters

- Ward Pigman

- Lee Pressman

- Vincent Reno

- Julian Wadleigh

- Harold Ware

- Nathaniel Weyl

- Harry Dexter White

- Nathan Witt

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |