Abe Fortas facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Abe Fortas

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 4, 1965 – May 14, 1969 |

|

| Nominated by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Preceded by | Arthur Goldberg |

| Succeeded by | Harry Blackmun |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Abraham Fortas

June 19, 1910 Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | April 5, 1982 (aged 71) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Carolyn Agger

(m. 1935) |

| Education | Rhodes College (BA) Yale University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1940 |

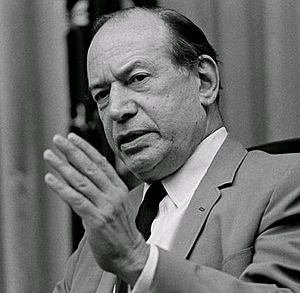

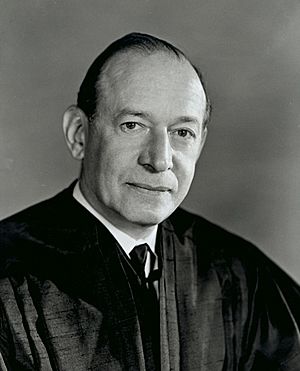

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969.

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas studied at Rhodes College and Yale Law School. He became a law professor and later advised the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Fortas also worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt and helped set up the United Nations in 1945.

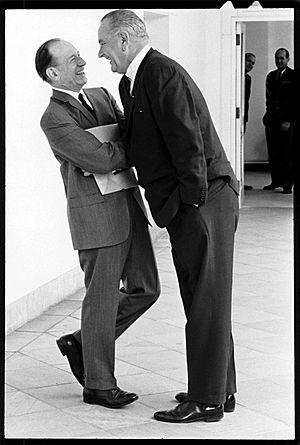

In 1948, Fortas helped Lyndon B. Johnson in a very close election. This created a strong friendship between them. Fortas also represented Clarence Earl Gideon in a famous case about the right to counsel (the right to have a lawyer).

President Johnson nominated Fortas to the Supreme Court in 1965. The Senate approved his nomination. As a Justice, Fortas wrote important decisions, including Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District.

In 1968, Johnson tried to make Fortas the chief justice. However, this plan failed due to strong opposition in the Senate. Fortas later resigned from the Court. This happened after a controversy involving money he received from a businessman who was being investigated. After leaving the Court, Fortas worked as a private lawyer again.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Fortas was the youngest of five children. His parents, Woolfe and Rachel Fortas, were Jewish immigrants. They came from Russia and Lithuania. Woolfe was a cabinetmaker, and they ran a store together.

Fortas loved music, especially the violin. He learned to play from Catholic nuns and a local music teacher. He was known as "Fiddlin' Abe Fortas."

He graduated from South Side High School in 1926 at age sixteen. He was second in his class. Fortas then won a scholarship to Rhodes College. He first thought about studying music but chose English and political science. He graduated first in his class in 1930.

Fortas received scholarships to both Harvard Law School and Yale Law School. He chose Yale and became its youngest law student at 20. He was the editor-in-chief of the Yale Law Journal and graduated with high honors in 1933.

One of his professors, William O. Douglas, was very impressed with Fortas. Douglas helped Fortas become an assistant law professor at Yale. Later, Douglas took government jobs in Washington, D.C. Fortas traveled between Yale and Washington to do his work.

Personal Life

In 1935, Fortas married Carolyn E. Agger. She became a successful tax lawyer. They did not have children. After he joined the Supreme Court, they lived in Georgetown, Washington, D.C.

Fortas was a talented amateur musician. He played the violin in a quartet on Sunday evenings. Famous musicians like Isaac Stern sometimes joined them.

Fortas was also a close friend of Luis Muñoz Marín, the first elected Governor of Puerto Rico. Fortas often visited Puerto Rico and helped the island's interests in Congress. He also helped write the Constitution of Puerto Rico.

The actor José Ferrer played Fortas in the 1980 film Gideon's Trumpet.

Early Career in Government

In 1939, Fortas left Yale to work for the government. He served as general counsel for the Public Works Administration. Then he became Undersecretary of the Interior under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. While working there, he met a young congressman from Texas, Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1945, Fortas briefly joined the military but was discharged due to a health issue. Later that year, President Harry S. Truman appointed him as an advisor. He helped the U.S. delegation during the first meetings of the United Nations (UN) in San Francisco and London.

Private Law Practice

In 1946, Fortas started his own law firm, Arnold & Fortas. It became one of Washington's most important law firms.

In 1948, Lyndon Johnson was running for the U.S. Senate in Texas. He won the primary election by only 87 votes. His opponent claimed there was cheating and tried to stop Johnson from being on the ballot. Johnson asked Fortas for help. Fortas convinced Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black to overturn the ruling. Johnson then won the election and became a U.S. Senator.

During the "Red Scare" in the 1940s and 1950s, many Americans feared communism. Fortas became well-known for defending Owen Lattimore. Lattimore was accused of being a communist. Fortas often argued with Senator Joseph McCarthy while defending Lattimore.

Fortas first opposed creating a special commission to investigate the assassination of John F. Kennedy. But when many groups started their own investigations, Fortas changed his mind. He advised President Johnson to create the Warren Commission.

Key Cases as a Lawyer

Durham v. United States

Fortas was interested in psychiatry, which was a new field at the time. In 1953, he represented Monte W. Durham. Durham's defense claimed he was not guilty due to insanity.

At the time, courts used old rules that made it hard to use psychiatric evidence. Fortas argued that these rules were outdated. The Court of Appeals agreed with Fortas. This decision changed American criminal law. It allowed courts to consider evidence about a defendant's mental state.

Gideon v. Wainwright

In 1963, Fortas represented Clarence Earl Gideon before the Supreme Court. Gideon had been convicted of breaking into a pool hall. He could not afford a lawyer, and the court did not provide one.

In a famous decision, Gideon v. Wainwright, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Gideon. The Court said that state courts must provide lawyers for criminal defendants who cannot afford one. This is required by the Sixth Amendment. Fortas's former professor, William O. Douglas, called his argument "probably the best single legal argument" he had heard in his 36 years on the Court.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court

On July 28, 1965, President Johnson nominated Fortas to the Supreme Court of the United States. He replaced Arthur Goldberg, who became the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Johnson wanted Fortas on the Court because he believed Fortas would support his "Great Society" programs.

The Senate approved Fortas's nomination on August 11, 1965. He took his oath on October 4, 1965. His appointment helped keep the Court's liberal majority during the Warren Court era.

The seat Fortas took was sometimes called the "Jewish seat." This was because the three justices before him—Goldberg, Felix Frankfurter, and Benjamin Cardozo—were also Jewish.

Fortas continued to advise President Johnson even after becoming a Justice. He attended White House meetings and discussed Court matters with the president. In 1966, he helped edit Johnson's State of the Union Address.

In 1968, Fortas wrote a book called Concerning Dissent and Civil Disobedience.

Children's and Students' Rights

During his time on the Court, Fortas greatly changed juvenile justice in the U.S. He extended due process rights to young people. Before this, the state often acted as a parent (parens patriae). This meant children accused of crimes did not always get a chance to defend themselves.

In Kent v. United States (1966), Fortas wrote the majority decision. This was the first Supreme Court case to look at juvenile court procedures. Fortas said the old system might be "the worst of both worlds." His opinion meant that young people in certain legal cases gained rights. These included the right to notice, the right to a lawyer, and the right against self-incrimination.

Two years later, Fortas wrote another important decision for children's rights. This was in the case of Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. This case involved students who were suspended for wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam War.

Fortas wrote that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." This decision extended First Amendment rights to students for the first time.

Epperson v. Arkansas

In 1968, Fortas helped the Court hear the case of Sue Epperson. She was a teacher who challenged Arkansas's law against teaching evolution. The Arkansas Supreme Court had overturned her win.

Fortas wrote the main opinion in Epperson v. Arkansas. This landmark decision banned teaching religiously based creationism in public school science classes.

Nomination for Chief Justice

On June 26, 1968, President Johnson nominated Fortas to be Chief Justice of the United States. He would replace Earl Warren, who was retiring. Johnson also announced that he would fill Fortas's old seat with Judge Homer Thornberry.

Some senators opposed Fortas's nomination. They worried about his liberal views. This was the first time a sitting Justice nominated for Chief Justice appeared before the Senate. Fortas answered questions for four days about his legal career and his relationship with President Johnson.

Some people also opposed Fortas because he was Jewish. The White House tried to get support for Fortas by pointing out this unfair opposition. Fortas himself called the effort to stop his nomination "anti-Negro, anti-liberal, anti-civil rights, [and] anti-Semitic."

Concerns About Payments

Fortas's acceptance of $15,000 for speaking at American University caused controversy. This money came from private sources connected to businesses. Some senators worried that Fortas might not be fair if cases involving these companies came to the Court. While legal, the large amount of money raised concerns about the Court's independence. The $15,000 was more than 40% of a Justice's yearly salary at the time.

Senate Vote and Withdrawal

On September 17, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted to approve Fortas's nomination. However, Senator Strom Thurmond promised to delay the vote. When the Senate debate began, opponents repeated their criticisms.

The debate lasted four days. A vote to end the debate failed. It was 14 votes short of the two-thirds needed to force a final vote. Because of this, President Johnson withdrew Fortas's nomination.

Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential election. Johnson did not make another nomination. Earl Warren was replaced by Warren Burger as chief justice in June 1969.

Later Years

After resigning, Fortas started a new law firm, Fortas and Koven. He had a successful law practice until his death in 1982. His wife, Carolyn Agger, stayed at his original firm. Fortas turned down an offer to write his life story.

Fortas remained good friends with Lyndon Johnson. He often visited the former president at his ranch until Johnson's death in 1973. Fortas also kept two important non-paying clients: the famous musician Pablo Casals and Lyndon Johnson.

Fortas served on the board of directors for Carnegie Hall and the Kennedy Center.

After returning to private practice, Fortas sometimes argued cases before the Supreme Court. His successor, Harry Blackmun, remembered seeing Fortas in court. Blackmun said Fortas showed no anger or sadness.

Fortas died on April 5, 1982, from a heart issue. His memorial service was held at the Kennedy Center.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2)

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Warren Court

Images for kids

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |