Owen Lattimore facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Owen Lattimore

|

|

|---|---|

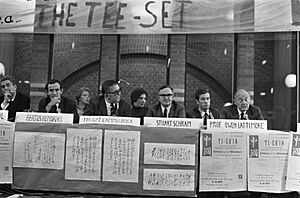

Owen Lattimore (around 1945)

|

|

| Born | July 27, 1900 Washington, D.C., US

|

| Died | May 31, 1989 (aged 88) |

| Other names | Chinese: 欧文·拉铁摩尔 |

| Occupation | Orientalist, writer |

Owen Lattimore (July 29, 1900 – May 31, 1989) was an American scholar and writer who studied Asia, especially China and Mongolia. Even though he never finished college, he became a very important expert on these regions.

In the 1930s, he edited Pacific Affairs, a journal about Asian topics. He also taught at Johns Hopkins University from 1938 to 1963. During World War II, he advised the American government and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek on Asian policy. Later, from 1963 to 1970, he was the first Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Leeds in England.

After World War II, during a time called McCarthyism in the U.S., some people were wrongly accused of being spies or having communist ideas. In 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy accused Lattimore of being a "top Russian spy." These accusations led to many government hearings. No proof was ever found that Lattimore was a spy. However, the hearings did show that Lattimore had sometimes spoken positively about the Soviet Union. This controversy ended his role as a government advisor and later affected his teaching career in the U.S. He passed away in 1989.

Lattimore's main goal as a scholar was to understand how human societies form, change, and interact, especially in "frontier" areas where different cultures meet. He studied many ideas, including how the environment shapes societies and how different types of civilizations (like farming and nomadic groups) influenced each other. His most famous book, The Inner Asian Frontiers of China (1940), explored these ideas.

Contents

Early Life and Adventures

Owen Lattimore was born in the United States but grew up in Tianjin, China. His parents, David and Margaret Lattimore, were English teachers at a Chinese university. His brother, Richmond Lattimore, became a famous poet.

Owen was taught at home by his mother. When he was twelve, he went to school in Switzerland. After World War I started in 1914, he moved to England and attended St Bees School until 1919. He loved reading and writing, especially poetry. He did well on his entrance exams for Oxford University. However, he didn't have enough money to attend, so he returned to China in 1919.

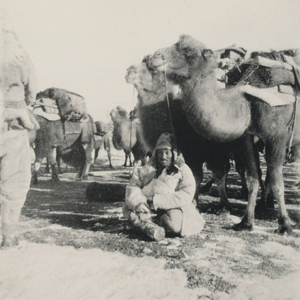

He first worked for a newspaper, then for a British trading company. This job allowed him to travel a lot in China. He also studied the Chinese language with a traditional scholar. His travels helped him understand real life and the economy in China. A big moment was when he helped a train full of wool pass through areas controlled by two fighting warlords in 1925. This experience led him to follow trade routes across Inner Mongolia to Xinjiang the next year.

His company didn't want to pay for his travels, but they sent him to Beijing for a year to work with the government. In Beijing, he met his future wife, Eleanor Holgate. For their honeymoon, they planned an amazing trip from Beijing to India. He would travel overland, and she would go by train across Siberia. Their plans changed, and Eleanor had to travel alone by horse-drawn sled for 400 miles in February to find him! She wrote about her journey in Turkestan Reunion (1934). Owen wrote about his travels in The Desert Road to Turkestan (1928) and High Tartary (1930). These trips sparked his lifelong interest in the Mongols and other people along the Silk Road.

After returning to America in 1928, he received a special scholarship for more travel in Manchuria. He also studied at Harvard University for a year. He didn't pursue a Ph.D. but returned to China from 1930 to 1933 with more scholarships.

In 1942, he received the Patron's Medal from the British Royal Geographical Society for his travels in Central Asia. In 1943, he was chosen to be a member of the American Philosophical Society, a group of important thinkers.

A Scholar and Editor

In 1934, Owen Lattimore became the editor of Pacific Affairs, a journal published by the Institute of Pacific Relations. He edited it from Beijing. He wanted the journal to be a place for different ideas and debates, not just official statements. He later said he often got into trouble with different groups because he wanted to publish many viewpoints.

Lattimore tried to get articles from many different scholars and writers, including Pearl S. Buck and some Chinese writers. He made the journal a place for new ideas, especially from social sciences.

In 1936, Lattimore visited Moscow in the Soviet Union. He wanted Soviet scholars to contribute to his journal. However, Soviet officials demanded that his journal support their political goals against Japan. Lattimore refused, saying Pacific Affairs had to serve all countries and couldn't take political sides. He was also denied permission to visit Mongolia. In the end, Soviet scholars sent only one article to the journal.

The Lattimores returned to Beijing in 1937. Owen visited the Communist headquarters in Yan'an, China. He met Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, who impressed him. However, when he spoke to Mongols in their own language at a party school, his Chinese hosts stopped the meeting.

In 1938, the Lattimores left China. Owen continued to edit Pacific Affairs from California. During this time, he made a mistake that he later regretted. He published an article that praised Stalin's trials in the Soviet Union, saying they made the Soviet Union stronger. Lattimore even said these trials "sound to me like democracy." He later admitted he was wrong about this.

He also wrote that the U.S. should not let Russia expand into China. He believed that Japan's harsh actions in China were actually helping communism spread by destroying Chinese wealth and weakening groups that were against communism.

In 1938, Lattimore wrote about Japan's planned attack on a Muslim region in China. He predicted that the Japanese would suffer a huge defeat. In 1940, the Japanese were indeed defeated by Muslim Chinese forces led by General Ma Hongbin at the Battle of West Suiyuan.

World War II and Accusations

After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Lattimore to advise Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. Lattimore suggested that China should give more freedom to its ethnic minority groups, similar to how the Soviet Union handled its minorities. However, Chiang's officials mostly ignored his advice.

In 1944, Lattimore was put in charge of the Pacific area for the Office of War Information, a U.S. government agency. By this time, the FBI had been watching his activities for two years.

Also in 1944, President Roosevelt asked Lattimore to join Vice-President Henry A. Wallace on a trip to Siberia, China, and Mongolia. During this trip, Wallace and Lattimore visited a Soviet labor camp called Gulag in Kolyma. In an article for National Geographic, Lattimore described what he saw as a mix of a trading company and a development project. He said the prisoners looked strong and well-fed. Later, in 1968, he explained that his role was not to investigate his hosts.

During the 1940s, Lattimore had disagreements with Alfred Kohlberg, a businessman who believed Lattimore was too sympathetic to the Chinese Communist Party and not supportive enough of Chiang Kai-shek. Kohlberg later became an advisor to Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Facing Accusations

In 1948, a former Soviet official named Alexander Barmine told the FBI that Lattimore was a Soviet agent. This accusation later became public.

In March 1950, Senator Joseph McCarthy publicly accused Lattimore of being the "top Soviet agent" in the United States. McCarthy's committee was investigating claims of Soviet spies in the U.S. government. Lattimore was in Kabul, Afghanistan, at the time. He called the charges "moonshine" and quickly returned to the U.S. to defend himself.

McCarthy had no strong evidence that Lattimore was a spy or a secret communist. He brought in a former Communist Party editor, Louis F. Budenz, to testify. Budenz had no direct knowledge but claimed Lattimore was a secret communist who helped Soviet policy without using communist language. The committee's majority report cleared Lattimore of all charges.

In 1952, Lattimore was called to testify again before another Senate committee led by Senator Pat McCarran. This committee seized all the records of the Institute of Pacific Relations. Lattimore's testimony lasted twelve days and was full of arguments. Budenz again testified, this time claiming Lattimore was both a communist and a Soviet agent.

Other scholars also testified. Some said Lattimore's writings were not deep enough. A former communist scholar, Karl August Wittfogel, suggested that Lattimore knew about his communist background. Lattimore denied this. Wittfogel and another historian, George Taylor, said Lattimore had harmed the "free world" by not focusing on defeating communism. They also said Lattimore's use of the word "feudal" showed Marxist influence, but Lattimore replied that Marxists didn't "own" that word.

In 1952, after 17 months of investigation, the McCarran Committee released a report. It stated that Lattimore was a "conscious instrument of the Soviet conspiracy" and had not told the whole truth. Lattimore was then accused of perjury (lying under oath) on seven different counts. His lawyers argued that the questions were tricky and about old, unclear details.

Within three years, a federal judge dismissed the perjury charges. The judge said four of the charges were not strong enough. He also said that denying sympathy for communism was too vague to be answered fairly. Former FBI agent William C. Sullivan later said in his memoir that the FBI never found "anything substantial" against Lattimore and that the accusations were "ridiculous."

His Lasting Impact

In 1963, Owen Lattimore moved from Johns Hopkins University to the University of Leeds in England. There, he started the Department of Chinese Studies (now East Asian Studies). He also promoted the study of Mongolia, building good relationships between Leeds and Mongolia. He retired in 1970.

In 1984, the University of Leeds gave him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree.

Lattimore always worked to create research centers for Mongolian history and culture. In 1979, he became the first Westerner to receive the Order of the Polar Star, Mongolia's highest award for foreigners. In 1986, a newly found dinosaur was named after him in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

In 2008, a conference was held in Mongolia to discuss Owen Lattimore's influence on Inner Asian studies.

Some anti-Communist political figures had mixed views on Lattimore. For example, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. thought Lattimore wasn't a spy but might have been very committed to communist ideas.

Lattimore's Theories

Historian Peter Perdue noted that modern scholars still use Lattimore's ideas, even if they have updated some of his arguments. His insights continue to inspire historians today.

In his 1947 book, An Inner Asian Approach to the Historical Geography of China, Lattimore explored how people affect the environment and how the environment, in turn, changes people. He believed that civilization is shaped by its own impact on nature. He described a pattern:

- A very early society does some farming but knows it has limits.

- As the society grows, it starts to change the environment. For example, it might use up wild animals and plants, so it begins to raise animals and grow crops. It might cut down forests to make room for these activities.

- The environment changes, creating new chances. For example, it might become grasslands.

- Society then changes in response to these new chances. For example, people who used to move around a lot might build permanent homes and become farmers instead of hunter-gatherers.

- This back-and-forth process continues, leading to new ways of life.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |