Zhou Enlai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Zhou Enlai

|

|

|---|---|

|

周恩来

|

|

Zhou's official portrait

|

|

| 1st Premier of the People's Republic of China | |

| In office 27 September 1954 – 8 January 1976 |

|

| Leader | Mao Zedong |

| 1st vice-premier | Dong Biwu Chen Yun Lin Biao Deng Xiaoping |

| Preceded by | Mao Zedong (as Chairman of the People's Central Government of People's Republic of China) Himself (as Premier of Government Administration Council of the Central People's Government) |

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng |

| 1st Foreign Minister of the People's Republic of China | |

| In office 1 October 1949 – 11 February 1958 |

|

| Premier | Himself |

| Preceded by | Hu Shih (as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China) |

| Succeeded by | Chen Yi |

| First Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 30 August 1973 – 8 January 1976 |

|

| Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| Preceded by | Lin Biao (1971) |

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng |

| Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office 28 September 1956 – 1 August 1966 |

|

| Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| 2nd Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |

| In office December 1954 – 8 January 1976 |

|

| Honorary Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| Preceded by | Mao Zedong |

| Succeeded by | Vacant (1976–1978) Deng Xiaoping |

| Premier of Government Administration Council of the Central People's Government | |

| In office 21 October 1949 – 26 September 1954 |

|

| Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| Preceded by | New Post |

| Succeeded by | himself (as Premier of the People's Republic of China) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 March 1898 Huai'an, Jiangsu, Qing Dynasty |

| Died | 8 January 1976 (aged 77) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party (1921–1976) |

| Other political affiliations |

Kuomintang (1923–1927) |

| Spouse |

Deng Yingchao

(m. 1925) |

| Children | Sun Weishi, Wang Shu (both adopted) |

| Education | Nankai Middle School |

| Alma mater | Nankai University |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | National Revolutionary Army (1937-1945) Chinese Red Army People's Liberation Army |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Zhou Enlai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 周恩来 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 周恩來 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 翔宇 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Zhou Enlai (Chinese: 周恩来; pinyin: Zhōu Ēnlái; Wade–Giles: Chou1 Ên1-lai2; 5 March 1898 – 8 January 1976) was a very important Chinese leader. He was the first Premier of the People's Republic of China from 1949 until his death in 1976. Zhou worked closely with Chairman Mao Zedong. He helped the Communist Party gain power and then helped build China's relationships with other countries and its economy.

As a diplomat, Zhou was China's foreign minister from 1949 to 1958. He believed in living peacefully with Western countries after the Korean War. He took part in important meetings like the 1954 Geneva Conference and the 1955 Bandung Conference. He also helped arrange Richard Nixon's visit to China in 1972. Zhou helped create policies for dealing with countries like the United States, the Soviet Union, India, Korea, and Vietnam.

Zhou was able to stay in power during the difficult Cultural Revolution. While Mao focused on political ideas, Zhou managed the country's daily business. He tried to reduce the harm caused by the Red Guards and protect people from their anger. This made him very popular later in the Cultural Revolution.

Mao's health got worse in 1971, and Lin Biao died. Because of these events, Zhou was chosen as the First Vice Chairman of the Communist Party in 1973. This meant he was expected to take over after Mao. However, he still faced challenges from a group called the Gang of Four. His last big public appearance was in January 1975, where he gave a report on the government's work. He then left public life for medical care and died a year later. Many people were very sad when he died. This sadness turned into anger against the Gang of Four, leading to the 1976 Tiananmen Incident. Zhou's friend, Deng Xiaoping, later became China's top leader.

Contents

- Zhou Enlai's Early Life

- Zhou's Time in Europe

- Zhou's Role in Whampoa Military Academy

- The Nationalist-Communist Split

- Zhou During the Chinese Civil War

- Zhou During World War II

- Diplomacy with the United States

- Return to Civil War

- Zhou as a PRC Diplomat and Statesman

- The Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution

- Zhou Enlai's Death

- Zhou Enlai's Legacy

- Awards and Honors

- Works

- See also

Zhou Enlai's Early Life

Growing Up in China

Zhou Enlai was born in Huai'an, Jiangsu province, on March 5, 1898. His family came from Shaoxing in Zhejiang province. For many generations, men in his family worked as government clerks. To get better jobs, they often had to move. Zhou Enlai's family moved to Huai'an, but they still thought of Shaoxing as their original home.

Zhou's grandfather and granduncle were the first to move to Huai'an. Zhou's father, Zhou Yineng, was known for being honest and kind, but he struggled to support his family. He often traveled across China for different jobs. Zhou Enlai remembered his father being away from home a lot.

When Zhou was very young, he was adopted by his father's younger brother, Zhou Yigan, who was sick. The family wanted Yigan to have an heir. Zhou Yigan died soon after, and Zhou Enlai was raised by Yigan's wife, Madame Chen. Madame Chen was educated and taught Zhou to read and write early. Zhou said he learned to love Chinese literature and opera from her. He read famous Chinese novels like Journey to the West and Romance of the Three Kingdoms when he was young.

Zhou's birth mother died when he was 9, and his adoptive mother died when he was 10. Since his father was far away, Zhou and his two younger brothers lived with another uncle for two years. In 1910, Zhou's older uncle, Yigeng, offered to care for him. Zhou went to live with this uncle in Shenyang, where his uncle worked for the government.

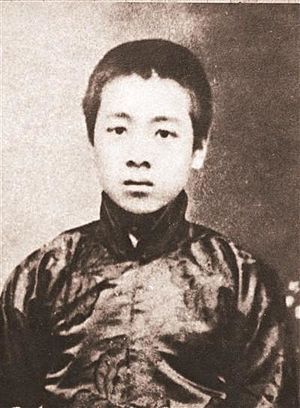

Zhou's Education Journey

In Shenyang, Zhou went to the Dongguan Model Academy, a modern school. Before this, he had only been taught at home. He learned new subjects like English and science. He also read about reformers who wanted to change China. When he was 14, Zhou said he wanted to "become a great man who will take up the heavy responsibilities of the country." In 1913, Zhou's uncle moved to Tianjin, and Zhou went to the famous Nankai Middle School.

Nankai Middle School was known for its unique teaching methods, similar to schools in the United States. It had a strict daily routine and moral code. Many students who went there later became important leaders. Zhou was very talented and caught the attention of the school's founders. One of them, Yan Xiu, even helped pay for Zhou's studies in Japan and France. Yan Xiu was so impressed that he wanted Zhou to marry his daughter, but Zhou politely declined.

Zhou did well in school, especially in Chinese. He won awards in the speech club and became editor of the school newspaper. He also loved acting and producing plays. Zhou's writings from this time show his discipline and care for his country. When he graduated in 1917, he was one of the top students. He left Nankai wanting to serve his country and gain the skills to do so.

After graduating, Zhou went to Japan in 1917 to study more. He spent most of his time in a language school for Chinese students. His family and Yan Xiu helped him with money, but it was limited. Zhou tried to get scholarships but failed to get into Japanese universities. He felt frustrated because he struggled with Japanese and faced discrimination. By 1919, when he returned to China, he was disappointed with Japanese culture and felt their political system was not right for China.

Zhou's diaries from Tokyo show he was very interested in politics, especially the Russian Revolution of 1917. He read a progressive magazine called New Youth. He also read early works on Marxism. His active role in political movements began after he returned to China.

Early Political Steps

Zhou returned to Tianjin in the spring of 1919. He became editor of the Tianjin Student Union Bulletin in July 1919. This newspaper was popular with students across China. In September, Zhou and other students formed a small group called the "Awakening Society." Zhou said their goal was to get rid of anything that stopped progress, like old ideas and unfairness. In this group, Zhou met Deng Yingchao, who would later become his wife.

Zhou became more involved in politics. He supported a boycott of Japanese goods. When the government tried to stop the boycott, Zhou led a march in January 1920 to ask for the release of arrested students. Zhou and three other leaders were arrested themselves. They were held for over six months. During this time, Zhou organized discussions about Marxism. After their release, Zhou decided to go to Europe to study. He left China in November 1920 with other students.

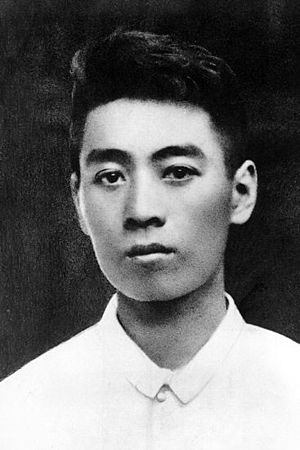

Zhou's Time in Europe

Learning and Organizing in Europe

Zhou arrived in France in December 1920. Unlike many Chinese students who had to work, Zhou had a scholarship and a job as a reporter. This allowed him to focus on revolutionary activities. He wanted to study how different countries solved social problems and apply those lessons to China.

In London, Zhou saw a large miners' strike and wrote articles about the conflict between workers and employers. He then moved to Paris, where people were very interested in Russia's 1917 revolution. Zhou thought China could either change slowly like England or through revolution like Russia. He hoped for something in between.

In spring 1921, Zhou joined a Chinese Communist group in Paris. He was recruited by Zhang Shenfu, whom he had met before. This group later joined with other Chinese students, including Deng Xiaoping. Zhou moved to Berlin in 1922, where the political atmosphere was more open. He traveled between Paris and Berlin.

In June 1922, Zhou helped create the Chinese Youth Communist Party in Paris, which was the European branch of the Chinese Communist Party. He helped write the party's rules and was in charge of propaganda. He also helped edit the party magazine. Zhou hired a young Deng Xiaoping to help with the magazine. Zhou also helped recruit students to study in Moscow and set up the European branch of the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang or KMT).

In 1923, the Chinese Communist Party decided to work with the KMT. Zhou helped organize the Nationalist Party's European branch in November 1923. Many of its leaders were actually Communists. Zhou's connections and friendships from this time were very important for his future career. He helped many important leaders, like Zhu De, join the party. By 1924, Zhou was called back to China as one of the most important Chinese Communist Party members in Europe.

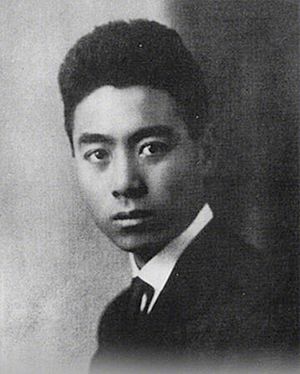

Zhou's Role in Whampoa Military Academy

Building Influence in Guangzhou

Zhou returned to China in late 1924 and joined the Political Department of the Whampoa Military Academy. This academy was a training center for the Nationalist Party Army, funded and staffed by the Soviets. Its goal was to train soldiers to unite China. Zhou became the deputy director, and later the director, of the Political Department. This department was in charge of teaching the cadets the KMT's ideas and boosting their loyalty.

Zhou was a very important figure at the academy, often speaking after the commandant, Chiang Kai-shek. He helped create the system where political officers (commissars) were part of the army. Zhou also became the secretary of the Communist Party in Guangdong-Guangxi. He worked hard to spread Communist ideas at the academy. He brought in other Communists to the Political Department and helped create student groups that were controlled by the Communists. He even set up a secret Communist Party branch at the academy.

Military Actions and Personal Life

Zhou took part in two military operations in 1925, known as the Eastern Expeditions. These campaigns fought against a military leader named Chen Jiongming. Zhou went with the Whampoa cadets as a political officer. In the second expedition, Zhou was appointed director of the First Corps Political Department. He became the chief political officer for the First Corps. This allowed him to place Communists as political officers in many divisions. After the expedition, Zhou helped set up a Communist Party branch and strengthen unions in the area. This was a high point for Zhou at Whampoa.

In his personal life, 1925 was also important. Zhou had stayed in touch with Deng Yingchao from the Awakening Society. They married in Guangzhou on August 8, 1925.

Zhou's time at Whampoa ended in March 1926 after an incident involving a gunboat. This led Chiang Kai-shek to remove Communists from high positions in the Nationalist Party. Zhou's work as a political officer in the military was very important for his career. He became a key Communist Party expert in military affairs. He also continued his secret activities, organizing Communist groups within the army and other armed groups. This work continued until the Nationalist and Communist parties fully separated in 1927.

The Nationalist-Communist Split

Working in Shanghai

Zhou's activities after leaving Whampoa are not fully clear. In July 1926, the Nationalists began the Northern Expedition to unite China. Chiang Kai-shek led this effort. As the expedition succeeded, the Nationalists and Communists competed for control of major southern cities like Shanghai. Shanghai was controlled by a military leader named Sun Chuanfang. The Communists, whose main office was in Shanghai, tried three times to take control of the city.

Zhou was sent to Shanghai to help with these efforts. He was in Shanghai by December 1926. Zhou was in charge of the Communist Party's Military Commission in Shanghai. He helped train workers for the Communist-controlled labor union. He also worked to make union groups stronger.

The third Communist uprising in Shanghai happened in March 1927. About 600,000 workers rioted, cutting power and phone lines and taking over important buildings. They were told not to harm foreigners, and they obeyed. The uprising was successful, and Nationalist troops entered the city the next day.

However, conflict soon began between the Nationalists and Communists. On April 12, Nationalist forces attacked the Communists. Zhou himself was almost captured but was released after someone intervened.

Escape and New Plans

Zhou fled Shanghai and went to Hankou (now part of Wuhan). He attended the Communist Party's 5th National Congress there. He was elected to the Party's Central Committee and again led the military department. After Chiang Kai-shek cracked down on the Communists, the Nationalist Party split. The Communists remained allied with the "left-wing" Nationalists, hoping to gain more influence. But this left-wing government also fell apart, and Chiang's troops began to remove Communists from areas they controlled. Zhou had to go into hiding.

Under pressure from their Soviet advisors, the Communists decided to start military revolts. The first was the Nanchang Revolt. Zhou was sent to oversee it, but it was a disaster, and Communist forces were scattered. Zhou got sick with malaria and was secretly sent to Hong Kong for medical treatment. Later, the Communist Party Central Committee blamed Zhou for the failure of the Nanchang campaign and temporarily lowered his rank.

Zhou During the Chinese Civil War

The Sixth Party Congress

After the Nanchang Uprising failed, Zhou went to the Soviet Union for the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) Sixth National Party Congress in Moscow in 1928. The meeting had to be held in Moscow because it was too dangerous in China. Zhou had to travel in disguise.

At the Congress, Zhou gave a long speech. He said that conditions in China were not ready for an immediate revolution. He believed the CCP should focus on gaining support from people in the countryside and setting up a Communist government in southern China, like the one Mao Zedong was already building. The Congress agreed with Zhou. Zhou became the director of the Central Committee Organization Department. He returned to China in 1929.

Working Underground

Back in Shanghai in 1929, Zhou began working secretly. He set up a network of hidden Communist groups. The biggest danger was being caught by the KMT secret police. To avoid being found, Zhou and his wife changed homes often and used different names. Zhou was very careful, making sure only a few people knew where he was. He disguised all Party offices and used passwords. He never used public transport and avoided public places.

In 1928, the CCP also created its own intelligence agency, which Zhou later controlled. This agency had sections for protecting Party members, gathering information, communicating, and even carrying out assassinations. Zhou's main goal was to put spies inside the KMT secret police. His agents were very successful, helping the CCP escape Chiang's attacks.

The Long March and Mao's Rise

After some military failures, the Communists decided to leave their bases in Jiangxi. Zhou was in charge of organizing this withdrawal, known as the Long March. He planned everything secretly to avoid heavy losses. He even negotiated with a KMT general to allow the Red Army to pass through his territory peacefully.

During the Long March, the Red Army suffered heavy losses. Zhou remained calm and kept his command. There were many disagreements among Communist leaders about what to do next. Zhou consistently supported Mao Zedong. Mao was gaining influence, and after a meeting in January 1935, Mao became Zhou's assistant. After the Long March ended in Shaanxi, Mao officially became the top leader of the CCP, and Zhou became vice-chairman. They kept these positions until their deaths.

The Xi'an Incident

In 1936, the Communist International (Comintern) changed its policy. Instead of fighting Chiang Kai-shek, they wanted to unite with him to fight Japan. Zhou was key in making this happen. He secretly contacted Zhang Xueliang, a KMT commander who wanted to fight Japan. Zhou convinced Zhang that the CCP would work with him.

In December 1936, Chiang Kai-shek went to Xi'an to push his forces to attack the Communists. Zhang Xueliang and his followers kidnapped Chiang Kai-shek in what became known as the Xi'an Incident. They wanted to force Chiang to fight Japan instead of the Communists.

Some Communist leaders, including Mao, wanted to kill Chiang. But others, like Zhou Enlai, saw it as a chance to unite against Japan. Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union also urged the CCP to release Chiang.

Zhou Enlai went to Xi'an as the chief Communist negotiator. Chiang was at first against talking to a Communist, but he realized his life depended on it. On December 24, Chiang met Zhou. It was their first meeting in over ten years. Zhou said that if Chiang stopped the civil war and fought Japan, the Red Army would follow his command. Chiang agreed to end the civil war and work together against Japan. He also invited Zhou to Nanjing for more talks.

After Chiang was released, some of Zhang's officers were angry and threatened Zhou. But Zhou, always a skilled diplomat, calmly defended his actions. He managed to calm them down, and they left him unharmed. Zhou tried to get Zhang released in later negotiations, but he failed.

Zhou During World War II

Propaganda and Secret Work in Wuhan

When the Nationalist capital of Nanjing fell to the Japanese in December 1937, Zhou went with the government to its temporary capital in Wuhan. As the main representative of the CCP, Zhou set up an official office to work with the KMT. He used this office to secretly recruit Communist agents and build Party groups in KMT-controlled areas.

Zhou was very good at organizing. He convinced the Nationalist government to approve and fund a Communist newspaper, Xinhua ribao ("New China Daily"), saying it would spread anti-Japanese messages. This newspaper became a major way for Communists to spread their ideas.

Zhou also got many Chinese thinkers and artists to promote resistance against Japan. He organized a big celebration in 1938 after a victory against the Japanese. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in parades and sang resistance songs. Zhou himself donated money to the effort.

While in Wuhan, Zhou was the CCP's main contact with the outside world. He worked hard to change how people saw the Communists, from a "bandit organization" to a respected group. He met with many foreign journalists and writers, who often became sympathetic to the Communist cause. He also arranged for a Canadian medical team to go to Yan'an and helped a Dutch filmmaker make a documentary about China.

Military Strategy and Adopting Children

In January 1938, the Nationalist government made Zhou a deputy director in the Military Committee. Zhou was the only Communist to hold such a high position in the Nationalist government. He used his influence to promote capable Nationalist generals and encourage cooperation with the Red Army.

In the Battle of Taierzhuang, Zhou helped ensure that a skilled Nationalist general was in command. He also promised that Communist armies would attack the Japanese from other directions. This battle was a big victory for the Nationalists.

Zhou and his wife, Deng Yingchao, did not have their own children. While working as a diplomat, Zhou met and befriended many orphans. In Wuhan in 1937, he adopted a young girl named Sun Weishi. Her father had been killed by the KMT. Zhou also adopted Sun's brother, Sun Yang. After the People's Republic of China was founded, Sun Yang became the president of a university.

In 1938, Zhou met another orphan, Li Peng, whose father had also been killed by the KMT. Zhou looked after Li Peng in Yan'an. After the war, Zhou helped Li Peng get an education in Moscow and prepared him for leadership. Li Peng later became Premier of China.

Moving to Chongqing and Secret Work

When the Japanese army neared Wuhan in 1938, the Nationalist Army fought them for months, allowing the KMT government to move further inland to Chongqing. On his way to Chongqing, Zhou almost died in a huge fire in Changsha. The Nationalist army had deliberately started the fire to stop the city from falling to the Japanese. Zhou demanded an investigation, and those responsible were punished.

Zhou Enlai reached Chongqing in December 1938. He continued his official and secret work there. He ran two pro-Communist newspapers and secretly built intelligence networks. He also worked to increase the popularity of Communist groups in southern China. His secret activities were very successful, greatly increasing CCP membership.

In 1939, Zhou had an accident while riding a horse in Yan'an and broke his elbow. He traveled to Moscow for medical treatment. He also updated the Comintern on the situation in China. His adopted daughter, Sun Weishi, went with him and stayed in Moscow to study theater.

When Zhou returned to Chongqing in 1940, relations between the KMT and CCP were getting worse. The two parties fought each other with arrests, executions, propaganda, and military clashes. The united front officially ended in January 1941 after a major incident where Communist soldiers were attacked by government troops.

Zhou responded by making Party operations more secret. He continued his propaganda efforts through newspapers and stayed in close contact with foreign journalists. He also improved CCP intelligence efforts, recruiting and training many Communist spies. One of his agents even told him that Adolf Hitler was planning to attack the Soviet Union, two days before it happened.

Economic and Diplomatic Efforts

Even with bad relations with Chiang Kai-shek, Zhou worked openly in Chongqing. He made friends with Chinese and foreign visitors and organized cultural events. He became close friends with General Feng Yuxiang, which allowed him to move freely among Nationalist Army officers. Zhou also convinced some Nationalist generals to secretly join the CCP or help the Communists with supplies and communication.

Zhou was the main CCP representative to the outside world in Chongqing. He and his team made a good impression on American, British, Canadian, and Russian diplomats. Visitors found Zhou charming, educated, hardworking, and modest. In 1941, he met Ernest Hemingway and his wife. They were very impressed with Zhou and believed the Communists would take over China.

Zhou funded his activities partly through donations from foreigners and Chinese living abroad. He also started and ran several businesses in KMT- and Japanese-controlled China. These businesses, including trading companies and factories, made big profits for the Communists.

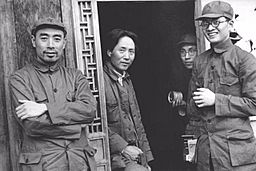

Relationship with Mao Zedong

In 1943, Zhou's relationship with Chiang Kai-shek worsened, and he returned to Yan'an permanently. By then, Mao Zedong had become the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party. Mao started a campaign to teach his political ideas (called "Mao Zedong Thought") to all Party members. This campaign helped create the strong support for Mao that later became a "personality cult."

When Zhou returned to Yan'an, he was criticized during this campaign. He was called an "empiricist" because he had worked with Mao's enemies. Mao publicly attacked Zhou. Zhou defended himself by making many public self-criticisms and praising Mao's leadership. He also joined Mao's allies in attacking Mao's enemies. Zhou's willingness to admit his "faults" and praise Mao convinced Mao that Zhou was loyal. By 1945, Mao was the clear leader of the CCP, and Mao Zedong Thought was firmly in place.

Diplomacy with the United States

The Dixie Mission and Peace Talks

As the United States planned to invade Japan, they wanted to contact the Communists in China. In 1944, Chiang Kai-shek allowed an American military group, the "Dixie mission," to visit Yan'an. Mao and Zhou welcomed them, hoping for American aid. They promised to help fight Japan and convinced the Americans that the CCP wanted a united Chinese government. Many Americans on the mission believed the CCP was working towards a democratic socialist future.

After Japan surrendered in 1945, Chiang invited Mao and Zhou to Chongqing for peace talks. There was fear in Yan'an that it was a trap. Zhou took charge of Mao's security. Mao and Zhou attended many public events together, and Zhou introduced Mao to important people.

During 43 days of talks, Mao and Chiang met many times, while Zhou worked on the details. The talks did not resolve anything. Zhou's offer to withdraw the Red Army was ignored. Mao returned to Yan'an, and Zhou followed later when fighting between Communists and Nationalists made more talks useless.

The Marshall Negotiations

In December 1945, US President Harry S. Truman sent General George Marshall to China to arrange a ceasefire between the CCP and KMT. Zhou and other CCP leaders hoped Marshall would be a more flexible negotiator. Zhou arrived in Chongqing to negotiate with Marshall.

The first talks went smoothly. Zhou represented the Communists, Marshall the Americans, and Zhang Qun the KMT. In January 1946, both sides agreed to stop fighting and reorganize their armies. Chiang promised political freedom and free elections. Zhou welcomed these statements and spoke against civil war.

However, the negotiations soon broke down. Neither the KMT nor the CCP wanted to give up their advantages. Military clashes became more frequent. In May 1946, Zhou and his wife moved to Nanjing, the Nationalist capital. Negotiations worsened. In October, Nationalist troops captured a Communist city. Chiang called a National Assembly without the CCP. On November 19, Zhou and the entire CCP delegation left Nanjing for Yan'an.

Return to Civil War

Military and Intelligence Leadership

After negotiations failed, the Chinese Civil War restarted. Zhou focused on military affairs and intelligence. He worked directly under Mao as his chief helper and as vice chairman of the Military Commission. He also continued to lead secret activities in KMT-controlled areas.

Nationalist troops captured Yan'an in March 1947. But Zhou's intelligence agents gave the Communist general, Peng Dehuai, detailed information about the KMT army. This allowed Communist forces to avoid big battles and use guerrilla warfare. This led to a series of victories for Peng. By early 1949, Communist forces controlled northern China, including Beijing and Tianjin.

Final Diplomacy and Victory

On January 21, 1949, Chiang Kai-shek stepped down as president. On April 1, 1949, his successor, Li Zongren, began peace talks with a six-member CCP team led by Zhou Enlai. Zhou started by asking why Li had visited Chiang before leaving Nanjing. Zhou said the CCP would not accept a fake peace controlled by Chiang. Negotiations continued, and Zhou presented a "final version" of a peace agreement, which was basically an ultimatum. The KMT government did not accept it.

On April 21, Mao and Zhou ordered the PLA to advance across the country. PLA troops captured Nanjing on April 23. In October, they captured Li's stronghold in Guangdong, forcing Li into exile. In December 1949, PLA troops captured Chengdu, the last KMT-controlled city on mainland China, forcing Chiang to move to Taiwan.

Zhou as a PRC Diplomat and Statesman

China's Place in the World in 1949

In the early 1950s, China's international influence was very low. Years of military defeats and foreign invasions had weakened it. The Korean War (1950–1953) made things worse, creating hostility with the United States. This meant Taiwan remained outside of China's control, and China could not join the United Nations for a long time.

After the People's Republic of China was founded on October 1, 1949, Zhou was made both Premier and Foreign Minister. In these roles, he shaped China's early foreign policy. He presented China as a new, responsible country on the world stage. Zhou was an experienced negotiator and a respected revolutionary leader.

Zhou worked to improve China's image by inviting important Chinese politicians, business leaders, and military figures who were not Communists to join the new government. He convinced many to accept positions, including Sun Yat-sen's widow, Soong Ching-ling, and a prominent industrialist, Huang Yanpei.

Diplomacy with India and the Korean War

Zhou's first diplomatic successes came from building a good relationship with India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Zhou convinced India to accept China's presence in Tibet. India later helped as a neutral mediator between China and the United States during the Korean War talks.

When the Korean War started in June 1950, Zhou and Mao discussed the possibility of American involvement. Zhou warned North Korea's leader, Kim Il-sung, to be careful. After the United States sent its fleet to the Taiwan Strait, Zhou criticized it as "armed aggression."

Zhou was worried the United States would invade North Korea or China. He got the Soviet Union to promise air support for Chinese forces. He also sent 260,000 Chinese soldiers to the North Korean border, with strict orders not to enter North Korea unless attacked. Zhou's military advisor predicted that General Douglas MacArthur would land at Incheon.

MacArthur did land at Incheon in September 1950, facing little resistance. On September 30, Zhou warned the United States that China would not tolerate foreign aggression against its neighbors. On October 1, South Korean troops crossed into North Korea. Stalin refused to get directly involved. Kim Il-sung desperately asked Mao for help.

Zhou was one of the few strong supporters of Mao's decision to send military aid to Korea. Zhou traveled to Moscow to get Stalin's support. Stalin agreed to send military equipment on credit, but his air force would only operate over Chinese airspace later.

On October 18, 1950, Zhou, Mao, and other leaders ordered 200,000 Chinese troops to enter North Korea. On November 13, Mao appointed Zhou as the overall commander of the People's Volunteer Army (PVA), China's forces in the Korean War. Peng Dehuai was the field commander.

By June 1951, the war was stuck around the Thirty-eighth Parallel. Zhou directed the truce talks, which began on July 10. The negotiations lasted two years, leading to a ceasefire agreement in July 1953. The Korean War was Zhou's last military assignment. He then focused on his work in the government and foreign affairs.

Working with Communist Neighbors

After Stalin died in 1953, Zhou went to his funeral in Moscow. Zhou was treated with great respect by Soviet officials. In 1954, the new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, visited Beijing.

Throughout the 1950s, Zhou worked to strengthen economic and political ties between China and other Communist countries. He signed agreements with the Mongolian People's Republic and North Korea to help rebuild their economies. He also held friendly talks with Burma's prime minister and supported China's efforts to send supplies to Ho Chi Minh's Vietnamese rebels.

The Geneva and Bandung Conferences

In April 1954, Zhou went to Switzerland for the Geneva Conference. This meeting aimed to end the war between France and Vietnam. Zhou's patience and cleverness helped the major powers reach an agreement. French Indochina was divided into Laos, Cambodia, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam. Elections were planned to unite Vietnam.

During the conference, Zhou met the American Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles. Zhou politely offered to shake his hand, but Dulles rudely turned away. Zhou calmly shrugged, turning a potentially embarrassing moment into a small victory. Zhou also had lunch with British actor Charlie Chaplin.

In 1955, Zhou was a key participant in the Asian–African Conference in Indonesia. This meeting of 29 African and Asian countries aimed to promote cooperation and oppose colonialism. Zhou skillfully made the United States seem like a threat to peace. He said, "the population of Asia will never forget that the first atom bomb was exploded on Asian soil." The conference called for peace, nuclear disarmament, and fair representation at the United Nations.

On his way to the Bandung conference, there was an assassination attempt on Zhou's plane. A bomb was planted, but Zhou changed planes at the last minute. All 11 other passengers died. Zhou used this incident to warn the British about KMT spies in Hong Kong. The official reason for Zhou's absence was that he had surgery.

After the Bandung conference, China's international standing slowly improved. Many nonaligned countries helped reduce the US-backed boycott of China. In 1971, China gained its seat at the United Nations.

China's Stance on Taiwan

When the People's Republic of China was founded in 1949, Zhou announced that any country wanting to have diplomatic ties with China must end relations with the former government on Taiwan. This was the new government's first foreign policy statement. By 1950, China had diplomatic relations with other communist countries and 13 non-communist countries, but not with most Western governments.

After the Bandung conference, Zhou was seen as a flexible negotiator. He realized the United States would protect Taiwan with military force. So, he convinced his government to stop shelling the islands of Quemoy and Matsu and look for a diplomatic solution. In May 1955, Zhou stated that China would "strive for the liberation of Taiwan by peaceful means." He always argued that Taiwan was part of China and that resolving the conflict was an internal matter.

In 1958, Chen Yi took over as Foreign Minister. After Zhou left this role, China's diplomatic staff was reduced.

The Shanghai Communique

By the early 1970s, relations between China and the United States began to get better. China needed American technology for its growing oil industry. In January 1970, China invited the American ping-pong team to visit, starting "ping-pong diplomacy".

In 1971, Zhou Enlai secretly met with President Nixon's security advisor, Henry Kissinger. Kissinger was in China to prepare for a meeting between Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong. During these meetings, the United States agreed to allow money transfers to China, allow American-owned ships to trade with China, and allow Chinese goods into the United States for the first time since the Korean War. These talks were so secret that they were hidden from the American public and other governments.

On February 21, 1972, Richard Nixon arrived in Beijing and was greeted by Zhou. He later met with Mao Zedong. The main diplomatic outcome of Nixon's visit was the Shanghai Communique, signed on February 28. This document stated both sides' positions without trying to solve their differences. Both sides agreed to disagree on Taiwan. The Communique encouraged more diplomatic, cultural, and economic exchanges. This agreement was a major change in policy for both the United States and China.

The Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution

Zhou's Role in the Great Leap Forward

In 1958, Mao Zedong started the Great Leap Forward. This plan aimed to quickly increase China's production in factories and farms, but it set unrealistic goals. Zhou, known for being a practical leader, kept his position during this time. He has been described as helping to make Mao's ambitious, sometimes impossible, plans a reality.

By the early 1960s, Mao's reputation was not as strong. His economic policies had failed, and his lifestyle seemed out of touch with many old friends. Other leaders, including Zhou Enlai, began to question Mao's vision of constant revolution.

Surviving the Cultural Revolution

To improve his image and power, Mao, with help from Lin Biao, launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966. This movement was strongly pro-Mao and allowed him to remove political enemies from the government. Schools and universities closed, and young Chinese were encouraged to destroy old buildings and attack their teachers and party leaders. Many top Communist leaders, like President Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, were removed from their jobs and publicly shamed.

Zhou tried to argue that Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping should be allowed to return to work, but Mao and his allies opposed this. Zhou was even warned that he might be seen as "counter-revolutionary" if he didn't support Mao. After these threats, Zhou stopped his criticisms and worked more closely with Mao.

Zhou supported the creation of radical Red Guard groups. He joined Mao's allies in attacking other Red Guard groups. He later explained that his strategy for political survival was to follow the majority's direction. When accused of not being enthusiastic enough, he blamed his "poor understanding" of Mao's ideas. He secretly disliked these forces, calling them his "inferno," but outwardly supported them to survive.

Even though Zhou was not directly persecuted, he could not save many close to him, including his adopted daughter Sun Weishi and adopted son Sun Yang. After the Cultural Revolution, Sun Weishi's plays were performed again to criticize those blamed for her death.

For the next ten years, Mao largely made policies, and Zhou carried them out. Zhou tried to lessen the extreme actions of the Cultural Revolution. For example, he stopped Beijing from being renamed "East Is Red City" and protected ancient artifacts in the Forbidden City from being destroyed by Red Guards. Despite his efforts, Zhou was deeply affected by his inability to prevent many events of the Cultural Revolution. In his last years, Zhou pushed for the "Four Modernizations" to fix the damage caused by Mao's policies.

Later in the Cultural Revolution, Zhou became a target of political campaigns led by Mao and the Gang of Four. The "Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius" campaign in 1973-1974 was aimed at Zhou because he was seen as a main political opponent.

Zhou Enlai's Death

Illness and Passing Away

According to a biography by Gao Wenqian, Zhou was diagnosed with bladder cancer in November 1972. His doctors believed he had a good chance of recovery with treatment. However, Mao had to approve medical treatment for top leaders. Mao ordered that Zhou and his wife not be told of the diagnosis, and no surgery or further tests should be done. Henry Kissinger offered to send cancer specialists from the United States, but the offer was refused. After pressure from other Chinese leaders, Mao finally allowed surgery in June 1974. A series of operations over the next year and a half could not stop the cancer.

Zhou continued to work from the hospital. Deng Xiaoping, as First Deputy Premier, handled most important government matters. Zhou's last major public appearance was on January 13, 1975, where he presented a government report. He then left public view for more medical treatment. Zhou Enlai died from cancer at 9:57 AM on January 8, 1976, at the age of 77.

Public Mourning and Suppression

Whatever Mao's personal feelings, the public deeply mourned Zhou's death. Foreign reporters said Beijing looked like a ghost town. There was no burial ceremony, as Zhou had wished for his ashes to be scattered across his hometown's hills and rivers, not kept in a mausoleum. Zhou's death showed how much the Chinese people respected him. He was seen as a symbol of stability during a chaotic time. Many countries around the world sent their condolences.

Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping gave the eulogy at Zhou's state funeral on January 15, 1976. Deng's speech praised Zhou's character, which many saw as a subtle criticism of Mao and the Cultural Revolution leaders. After this, the Gang of Four and Hua Guofeng increased their persecution of Deng.

After Zhou's official memorial, his political enemies in the Party banned any further public mourning. They issued "five nos": no black armbands, no mourning wreaths, no mourning halls, no memorial activities, and no photos of Zhou. Years of anger over the Cultural Revolution, the public persecution of Deng Xiaoping (who was linked to Zhou), and the ban on mourning Zhou all combined. This led to widespread public unhappiness with Mao and his apparent successors.

Officials tried to enforce the "five nos" by removing memorials and tearing down posters. On March 25, 1976, a Shanghai newspaper published an article attacking Zhou. This and other propaganda efforts only made the public more attached to Zhou's memory. A fake document claiming to be Zhou's last will circulated, attacking Jiang Qing and praising Deng Xiaoping.

The Tiananmen Incident

A few months after Zhou's death, a huge public event happened. On April 4, 1976, the day before China's annual Qingming Festival (when Chinese honor ancestors), thousands gathered at the Monument to the People's Heroes in Tiananmen Square. They honored Zhou Enlai by placing wreaths, banners, poems, and flowers. While honoring Zhou, they also criticized Jiang Qing and others. Some slogans even criticized Mao and his Cultural Revolution.

Up to two million people may have visited Tiananmen Square that day. People from all parts of society, from farmers to high-ranking officials' children, took part. They were motivated by anger over Zhou's treatment, opposition to Mao's policies, worry for China's future, and defiance of those who tried to stop them from mourning. It was a spontaneous demonstration of public feeling. Deng Xiaoping was not there and told his children to stay away.

On the morning of April 5, crowds found that the memorials had been removed by police overnight. This angered them. Attempts to stop the mourners led to a violent riot. Police cars were set on fire, and a crowd of over 100,000 people forced their way into government buildings around the square.

Most of the crowd left by evening, but a small group remained and was arrested by security forces. Similar incidents happened in other Chinese cities. Because of his close connection to Zhou, Deng Xiaoping was formally removed from all his positions on April 7, after this "Tiananmen Incident".

After gaining power in 1980, Deng Xiaoping released those arrested in the Tiananmen Incident. This was part of his effort to reverse the negative effects of the Cultural Revolution.

Zhou Enlai's Legacy

By the end of his life, Zhou was widely seen as a symbol of fairness and balance in China. Since his death, he has been remembered as a skilled negotiator, a master of carrying out policies, a dedicated revolutionary, and a practical leader. He was known for his tireless work ethic, charm, and calm public manner. He was said to be the last traditional Chinese official in the Confucian style. Zhou's actions should be understood through his beliefs and personality. He showed the mix of old and new in a Communist leader with a traditional Chinese background: both conservative and radical, practical and idealistic.

Zhou strongly believed in the Communist ideals of the People's Republic. However, he is widely praised for trying to control the extreme policies of Mao within his power limits. It is believed he successfully protected many important cultural sites, like the Potala Palace and Forbidden City, from the Red Guards. He also shielded many top leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, and many officials, scholars, and artists from being removed from power. Deng Xiaoping once said that Zhou was "sometimes forced to act against his conscience to minimize the damage" from Mao's policies.

While many other Chinese leaders are criticized today, Zhou's image remains positive and respected in China. Many Chinese still see Zhou as perhaps the most humane leader of the 20th century. The Communist Party today promotes Zhou as a dedicated and selfless leader, a symbol of the Party. Historians often describe Zhou as cultured and educated, consistent, and calm, unlike Mao. After Mao's death, Chinese newspapers highlighted Zhou's logical, realistic, and calm leadership style.

However, some recent studies have looked at Zhou's later relationship with Mao and his actions during the Cultural Revolution. They suggest that Zhou was very submissive and loyal to Mao, even supporting or allowing the persecution of friends and family to avoid political trouble himself. After the PRC was founded, Zhou could not or would not protect the spies he had used during the wars, who were later persecuted. Early in the Cultural Revolution, he told Jiang Qing, "From now on you make all the decisions, and I'll make sure they're carried out." He also publicly said that his old friend, Liu Shaoqi, "deserved to die" for opposing Mao. To avoid being persecuted, Zhou passively accepted the persecution of many others, including his own brother.

Some people in China used to compare Zhou to a budaoweng (a tumbler), suggesting he was a political opportunist. Mao's personal doctor, Li Zhisui, described Zhou as "Mao's slave, absolutely obedient." He said Zhou did everything to be loyal to Mao and had no independent thoughts. Li also said Mao demanded total loyalty but looked down on Zhou because he was so submissive. Some critics say Zhou was too diplomatic, avoiding clear stances in difficult political situations and becoming unclear in his ideas.

Many defend Zhou's involvement in the Cultural Revolution by saying he had no choice but to face political ruin. Because of his influence and political skill, the entire government might have collapsed without his cooperation. Given the political situation in the last ten years of his life, it is unlikely he would have survived without actively helping Mao.

American leaders who met Zhou in 1971 greatly praised him. Henry Kissinger was very impressed with Zhou's intelligence and character. He called Zhou "one of the two or three most impressive men I have ever met." Kissinger noted Zhou's amazing knowledge of facts, including American events and his own background. Richard Nixon also said he was impressed with Zhou's "brilliance and dynamism."

After he came to power, Deng Xiaoping may have highlighted Zhou Enlai's achievements to distance the Communist Party from Mao's Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. Deng believed that Zhou's legacy and character could represent the Party's best qualities. Also, Deng received credit for successful economic policies that Zhou first suggested. By linking himself with the popular Zhou Enlai, Deng may have used Zhou's legacy as a political tool after his death.

Zhou remains a widely honored figure in China today. After the People's Republic of China was founded, Zhou ordered that his hometown of Huai'an not turn his house into a memorial or maintain his family tombs. These wishes were respected during his lifetime. But today, his family home and traditional family school have been restored. Many tourists visit them every year. In 1998, Huai'an opened a large park with a museum dedicated to Zhou's life to celebrate his 100th birthday. The park includes a copy of Xihuating, Zhou's living and working quarters in Beijing.

The city of Tianjin has a museum dedicated to Zhou and his wife, Deng Yingchao. The city of Nanjing has a memorial with a bronze statue of Zhou, remembering the Communist negotiations in 1946. Stamps honoring the first anniversary of Zhou's death were issued in 1977, and again in 1998 for his 100th birthday.

The 2013 historical drama film The Story of Zhou Enlai shows Zhou Enlai's trip in May 1961 during the Great Leap Forward. He investigated the situation in rural areas of Guiyang and Hebei.

Awards and Honors

Works

- Zhou Enlai (1981). Selected Works of Zhou Enlai. I (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0-8351-2251-4. http://book.theorychina.org/upload/8c8341c6-71df-464e-9544-a850a742a101/.

- — (1989). Selected Works of Zhou Enlai. II (1st ed.). Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0-8351-2251-4. http://book.theorychina.org/upload/ffa60e80-a69f-428e-905c-169338d0c892/.

See also

In Spanish: Zhou Enlai para niños

In Spanish: Zhou Enlai para niños

- History of the People's Republic of China

- History of the Chinese Communist Party

- Chinese Civil War

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Kuomintang

- Whampoa Military Academy

- Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary by Gao Wenqian

- Long March

- Xi'an Incident

- Bandung Conference

- Geneva Conference

- Shanghai Communique

- Great Leap Forward

- 1976 Tiananmen Incident

- Former Residence of Zhou Enlai in Huai'an

- Former Residence of Zhou Enlai in Shanghai

- Kashmir Princess

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |