Great Leap Forward facts for kids

The Great Leap Forward (Chinese: 大跃进; pinyin: Dàyuèjìn) was a big plan in China to quickly grow its economy and industry. It was started by the Communist leader Chairman Mao Zedong in 1958. The plan ended in 1962. The Great Leap Forward did not make China a strong industrial country as hoped. Instead, it caused a terrible famine that led to the deaths of millions of people. Some historians believe it was one of the largest famines ever.

Contents

Farming and Food Production

Mao Zedong wanted China to produce a lot of food for its own people. He also wanted China to grow enough food to export to other countries. To do this, he started the Great Leap Forward. Many farmers were forced to give their land to the government. They then had to work on large government farms called agricultural cooperatives.

Later, these cooperatives became even bigger, involving thousands of people. By 1958, almost all farmers (98%) were part of these large government farms.

In 1958, China had a good harvest. However, things started to change the next year.

People were told to plant seeds very close together. But this idea was wrong. Crops did not grow well when they were too crowded. This led to much less grain being harvested in 1959. After that, harvests continued to be bad because resources were not used wisely.

Building Industry

Mao believed that making a lot of grain and steel was key to China's economic growth. He thought China's industrial output would be greater than the UK's within 15 years. In August 1958, leaders decided to double steel production in just one year. People who disagreed with these fast plans faced very serious consequences.

The government invested a lot in large factories. Millions of Chinese people became government workers. By 1960, over 50 million people worked for the state. The number of people living in cities also grew by over 31 million. All these new workers needed food. This put a huge strain on the food supply from the countryside.

During this fast growth, planning was poor. There were often shortages of materials needed for production.

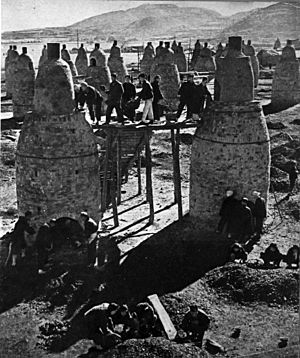

Backyard Steel Furnaces

Mao Zedong had little knowledge about how to make metal. Yet, he encouraged people to build small backyard steel furnaces everywhere. These were set up in every farming community and city neighborhood. Ordinary people, including farmers, worked hard to make steel from scrap metal.

To fuel these furnaces, people cut down trees. They even took wood from doors and furniture in their homes. Pots, pans, and other metal items were collected to provide "scrap" for the furnaces. This was done to meet the very high production goals. Many male farmers were taken away from harvesting crops to help make iron. Workers from factories, schools, and even hospitals also joined in.

However, the steel made in these backyard furnaces was of very poor quality. It was mostly useless lumps of pig iron. Mao did not trust experts like engineers. He believed more in the power of ordinary people working together.

Experts who knew better were afraid to speak up. This was because of what happened during the Hundred Flowers Campaign. Mao later learned that good quality steel could only be made in large factories using proper fuel like coal. But he did not immediately stop the backyard furnaces. He did not want to discourage people's excitement. The program was quietly stopped later that year.

Crop Problems and Famine

On the large government farms, new and unusual farming methods were tried. Many of these ideas came from a Soviet scientist named Trofim Lysenko. His ideas are now known to be wrong.

One idea was close cropping. Seeds were planted much closer together than normal. People wrongly thought that seeds of the same type would not compete with each other. Another idea was deep plowing, digging up to 2 meters deep. This was based on the mistaken belief that it would make plants grow extra-large roots. Some good land was left unplanted. The idea was to focus all effort on the most fertile land. But these untested ideas generally led to less grain being produced, not more.

Meanwhile, local leaders felt pressured to report higher and higher grain production numbers to the government. They would say they were making more food than they actually were. By 1959, China started running out of food. This was made worse because the country had sold some of its grain to other countries. Also, farm output was decreasing. People were not allowed to leave their areas. This meant they could not go look for food in other places. In some villages, a quarter or even a third of the people died.

The famine is believed to have killed between 16.5 million and 40 million people.

Mao stepped down as the leader of China on April 27, 1959. But he remained the head of the Communist Party. Liu Shaoqi (the new leader of China) and Deng Xiaoping (a key party official) were put in charge. They worked to change policies to help the economy recover.

Effects on the Economy

Bad Effects

The Great Leap Forward caused a huge amount of damage to homes. About 30% to 40% of all houses were destroyed. Homes were torn down to make fertilizer, build public dining halls, move villagers, or even to punish their owners.

Because of the food supply failures, the government slowly started to undo the large government farms in the 1960s. This was a step towards later changes under Deng Xiaoping.

Some members of the Communist Party bravely blamed the party leaders for the disaster. They believed China needed to focus more on education, technical skills, and business-like methods to grow the economy. Liu Shaoqi said in 1962 that the economic disaster was "30% fault of nature, 70% human error."

Grain production continued to drop for several years. In 1960–61, it fell by more than 25 percent.

Good Effects

Some historians argue that the Great Leap Forward did help China's overall economic growth after a difficult start. During this time, China also began to rapidly increase its production of tractors and fertilizer.

The Great Leap Forward encouraged everyone to work. This created new chances for women to work outside the home. As more people worked together on farms, women had more opportunities to gain economic and personal independence. Women became more needed in farming and factories. This led to the rise of "Iron Women." These women did jobs traditionally done by men in fields and factories. Many women also moved into management roles. They competed to be highly productive, and those who stood out were called Iron Women.

Related pages

See also

In Spanish: Gran Salto Adelante para niños

In Spanish: Gran Salto Adelante para niños

- List of campaigns of the Chinese Communist Party

- The Black Book of Communism

- Virgin Lands Campaign, a similar program in the Soviet Union

Images for kids

-

The Eurasian tree sparrow was the most notable target of the Four Pests Campaign.