Trofim Lysenko facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Trofim Lysenko

|

|

|---|---|

| Трофим Лысенко | |

Lysenko in 1938

|

|

| Born |

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko

29 September 1898 |

| Died | 20 November 1976 (aged 78) |

| Citizenship | Soviet Union |

| Alma mater | Kiev Agricultural Institute (1925) Uman Agropolytechnicum (1921) |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | Soviet Academy of Sciences |

| Notable students | Artavazd Avakyan, Pyotr Kononkov |

| Signature | |

Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (Russian: Трофи́м Дени́сович Лысе́нко; Ukrainian: Трохи́м Дени́сович Лисе́нко, romanized: Trokhym Denysovych Lysenko, IPA: [troˈxɪm deˈnɪsowɪtʃ lɪˈsɛnko]; 29 September [O.S. 17 September] 1898 – 20 November 1976) was a Soviet agronomist and scientist. He believed in Lamarckism, an idea that living things can pass on traits they gain during their lives. He did not agree with Mendelian genetics, which is the widely accepted science of how traits are passed down. Instead, he promoted his own ideas, which were later called Lysenkoism. Many scientists today consider his ideas to be pseudoscience, meaning they are not based on scientific facts.

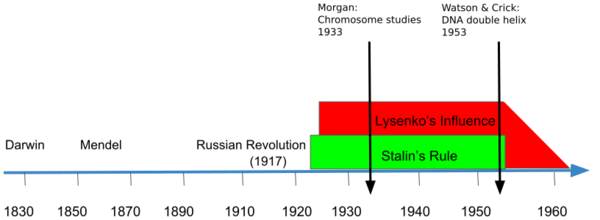

In 1940, Lysenko became the head of the Institute of Genetics of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. He used his power to silence scientists who disagreed with him. He even had some critics put in prison. His ideas became the official way of thinking about biology in the Soviet Union.

Scientists who did not agree with Lysenko lost their jobs and became very poor. Many were imprisoned, and some were even sentenced to death. One famous botanist, Nikolai Vavilov, was among them. Lysenko's ideas and methods also led to severe food shortages and famines in the Soviet Union. When China used his methods from 1958, it also caused a terrible famine.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Trofim Lysenko was born on September 29, 1898, in a small village called Karlovka in Ukraine. His family were farmers. He learned to read and write when he was 13 years old.

In 1913, he went to a horticulture (garden plant growing) school. He later graduated from a secondary horticulture school in Uman in 1921. During his studies, the area was affected by World War I and the Russian Civil War.

In 1922, Lysenko started studying at the Kiev Agricultural Institute. While studying, he worked at an experimental farm. He published his first scientific papers in 1923. He finished his agronomy degree in 1925.

Lysenko's Work and Rise to Power

Work in Azerbaijan

In 1925, Lysenko moved to Ganja, Azerbaijan, to work at a plant breeding station. His job was to introduce new crops like lupine and clover. These crops could help feed farm animals and make the soil better. Nikolai Vavilov, a famous scientist, supported Lysenko's early work.

Lysenko tried to grow crops like peas and wheat during harsh winters. He claimed he found a way to make fields fertile without using special fertilizers. He also said he could grow winter peas in Azerbaijan. The Soviet newspaper Pravda praised him for these claims.

Lysenko later married Alexandra Baskova, one of his students. He also worked with Donat Dolgushin, who would become a supporter.

Lysenko also studied how heat affects plant growth. He believed each plant needed a certain amount of heat to grow. He tried to link growth to days and temperature, but he made mistakes in his data analysis. When another expert, Nikolai Maximov, pointed this out, Lysenko did not like the criticism. After this, Lysenko famously said that math had no place in biology.

Support from Joseph Stalin

Lysenko's ideas about improving crop yields gained the support of the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. This was especially important after famines and food shortages in the early 1930s.

Stalin liked Lysenko because he came from a peasant family, just like Stalin claimed to support the working class. Lysenko also promised new farming methods that would help farmers. He helped convince farmers to return to work and feel like they were part of the Soviet plan.

By the late 1920s, Soviet leaders backed Lysenko. This was partly because the Communist Party wanted to promote people from working-class backgrounds into leadership roles. Lysenko became very powerful in Soviet genetics. He was the director of Genetics for the Academy of Sciences from 1940 until 1965.

Vernalization: A Key Idea

Lysenko was interested in changing winter wheat into spring wheat. In 1927, he started research that led to his 1928 paper on vernalization. This process involved treating wheat seeds with moisture and cold. This made them grow a crop when planted in spring.

Lysenko called this chilling process "Jarovization," which means "spring-izing." However, farmers had known about this method since the 1800s. Lysenko claimed that this change could be inherited by the next generation of plants. He believed the offspring would also be able to survive harsh winters.

Work in Odessa

In 1929, Lysenko was invited to Odessa to lead a plant vernalization laboratory. The People's Commissar of Agriculture, Alexander Schlichter, strongly supported his ideas. Lysenko became the director of the All-Union Breeding and Genetics Institute in 1936.

His work on vernalization was recognized at conferences. In 1933, he started experiments on planting potatoes in summer. He was elected to the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR in 1934. In 1935, he received the Order of Lenin.

Clash with Geneticists

In 1936, Lysenko argued with Vavilov and other geneticists. He disagreed with their scientific views and farming methods. Lysenko even denied the method of inbreeding crops.

The debate continued, and Lysenko started to attack his opponents. He accused geneticists of being "enemies of the people." The scientific discussion turned into a political fight. The International Genetic Congress in Moscow was canceled in 1937.

In 1938, Lysenko became president of the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences. He and his supporters continued to criticize other geneticists. They even compared Vavilov's work to anti-Marxist ideas.

In 1939, Lysenko claimed to have greatly increased millet yields. He said millet became the highest-yielding grain crop in 1940. He suggested a new way to prepare soil for planting.

In 1940, Lysenko arranged for a secret police officer to become deputy director of Vavilov's institute. Vavilov was arrested in August 1940 and died in prison in 1943. Many of Vavilov's colleagues were also arrested and died in custody.

World War II and After

During World War II, Lysenko continued his work on crops and potatoes. He received the Stalin Prize in 1943 for his potato planting method. In 1945, he was given the title of Hero of Socialist Labor.

After the war, Lysenko wrote articles promoting his "Michurinist genetics." He criticized the ideas of scientists like Thomas Hunt Morgan.

The 1948 VASKhNIL Session

In 1948, a major meeting of the All-Union Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL) took place. Most speakers at this meeting supported Lysenko's ideas. They claimed his methods had practical success.

At this session, Lysenko presented his views on genetics. He denied Mendel's law of segregation and the idea of unchanging "genes." He also made political attacks, saying that Morgan's genetics supported racism and served the rich.

Lysenko's Political Influence

During the early to mid-20th century, the Soviet Union faced war and revolution. The government wanted quick results in science. Lysenko promised to increase crop production and quality. He also impressed leaders by getting farmers to work.

The Soviet Union's forced collectivization (taking land from farmers) hurt food production. Many farmers left their lands or resisted. Lysenko became important by suggesting new farming methods. He also promised more work for farmers year-round. This helped the Soviet leaders get farmers involved in their plans.

Lysenko's success in encouraging farmers impressed Stalin. Lysenko's peasant background also appealed to Stalin. By the late 1920s, Soviet leaders supported Lysenko. This was partly because the Communist Party wanted to promote people from peasant backgrounds. Lysenko gained great power over genetics in the Soviet Union. He remained in charge during the time of Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev.

Scientists outside the Soviet Union criticized Lysenko. British biologist S. C. Harland said Lysenko knew nothing about genetics. Lysenko did not like this criticism. He called Western scientists "fly lovers and people haters."

Repression of Biologists

In 1937, Lysenko and his supporters began a campaign against geneticists. They accused them of working against Stalin.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the V.I. Lenin Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VASKhNIL) was a place for debates. In 1948, the VASKhNIL announced that Lysenkoism would be the only accepted theory. Soviet scientists had to reject any work that went against Lysenko.

Many geneticists who refused to agree with Lysenko were executed or sent to labor camps. Nikolai Vavilov, a famous Soviet geneticist, was arrested in 1940 and died in prison. Before the 1930s, the Soviet Union had a strong genetics community. Lysenko's actions greatly harmed Russian biology and agriculture for many years.

Consequences of Lysenko's Ideas

Lysenko made farmers plant seeds very close together. He believed that plants of the same "class" would not compete. His ideas and practices made food shortages worse in the Soviet Union.

When China adopted his methods in 1958, it led to the Great Chinese Famine from 1959 to 1962. Millions of people died during this famine.

After Stalin's Death

After Stalin died in 1953, Lysenko's influence slowly decreased. In 1955, over 300 scientists signed a letter against Lysenko. This led to him temporarily stepping down. However, he returned to power with the support of the new leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

Mainstream scientists began to speak out against Lysenko again. In 1962, three leading Soviet physicists called his work pseudoscience. They also criticized how he used political power to silence others.

In 1964, physicist Andrei Sakharov spoke against Lysenko. He said Lysenko was responsible for the backwardness of Soviet biology. He also blamed Lysenko for the harm and deaths of many real scientists.

The Soviet press then published many articles against Lysenko. They called for science to return to biology and agriculture. In 1965, Lysenko was removed from his position as director of the Institute of Genetics. His secretive methods were revealed. Lysenko was then disgraced in the Soviet Union.

It took many years for biology and agronomy to recover in Russia after Lysenko's control ended. Lysenko died in Moscow in 1976. The Soviet government did not announce his death for two days. They only put a small note in the newspaper.

Lysenko's Theories

Lysenko rejected the idea of Mendelian genetic inheritance. He called his own ideas "Michurinist genetics." He thought Gregor Mendel's theory was too old-fashioned. Lysenko's ideas were a mix of his own thoughts and those of other Soviet scientists.

A main idea was that body cells (soma) affect the traits of offspring. He believed every part of the body contributed to the cells that pass on traits. This was similar to Charles Darwin's idea of pangenesis. Lysenko, however, denied any connection to Darwin's theory.

Lysenko's ideas were not based on established biological theories like Mendelian genetics or Darwinism. He shaped his ideas to support his farming goals and to disprove other geneticists. His ideas are now known as "Lysenkoism." He claimed his ideas were not like Lamarckism, but they shared the belief that traits gained during life could be inherited.

Lysenko also had some unusual beliefs. He thought plants were "self-sacrificing." He claimed they died not from lack of sunlight, but to help new plants grow. He also believed that if you crossed two plants, the desired traits would always be passed on. This ignored the idea of variation or mutation.

Lysenko did not believe in genes. He thought that any living body could pass on its traits, not just special elements like DNA or genes. This confused other biologists because it went against what was known about heredity. Most scientists found his ideas unbelievable. Today, his beliefs are seen as pseudo-scientific.

Lysenko also argued that living things help each other, not just compete. He believed this was true both within the same species and between different species.

He stated that an organism and its environment are connected. Different living things need different conditions to grow. By studying these needs, we learn about their traits and how they inherit them.

Another of Lysenko's theories was about cows. He believed that how well cows were treated affected how much milk they produced, not their genetics. He and his followers were known for taking good care of their animals.

After World War II, Lysenko became interested in Olga Lepeshinskaya's work. She claimed she could create cells from egg yolk. By combining their ideas, they claimed that cells could grow from non-cellular material. This went against the basics of modern cytology and genetics.

Vernalization: A Closer Look

Lysenko worked on how low temperatures affect plant growth. He developed a method called vernalization. This involved germinating seeds at low temperatures before planting.

Some scientists initially supported this technique. Nikolai Vavilov thought it could simplify plant breeding. He also believed it could help protect winter crops from freezing. Vavilov saw vernalization as a great step in breeding. However, Vavilov later stopped supporting it because it did not produce the expected results.

Vernalized crops were planted more and more in the Soviet Union. By 1937, 8.9 million hectares were planted this way.

However, the widespread use of vernalization in Soviet agriculture failed. Critics said there was not enough experimental data for different plant types and regions. Data was collected using surveys, which made it easy to fake results. Lysenko's results were not published in independent scientific journals.

Experts criticized vernalization for several reasons. Seeds could be damaged during soaking and planting. The process was also very difficult and time-consuming. Vernalized plants were also more likely to get diseases.

After World War II, vernalization was not widely used in farming. The newspaper Pravda later said that with new farming technology, vernalization was "not always necessary." However, they still claimed it worked well for millet and potatoes.

Summer Potato Planting

In southern Soviet regions, potatoes often produced smaller tubers and rotted easily. Lysenko suggested planting potatoes in summer. He claimed that planting them in cool soil would stop the "deterioration of the breed."

He stated that summer planting could improve the potato breed. However, like with vernalization, data was collected using surveys, which could be faked. Any scientific data was never published.

When summer planting did not work, Lysenko suggested burying potatoes in trenches. He claimed this would reduce rotting. But this led to huge crop losses because the rotting actually got worse.

Lysenko ignored the real reason for potato problems: viruses. He banned research into plant viruses. This caused a big delay in finding ways to detect plant viruses in the Soviet Union. Viruses spread, and potato yields dropped sharply.

Inheritance of Acquired Traits

A big disagreement between Lysenko and other geneticists was about inherited traits. Lysenko believed that traits gained during an organism's life, like from environmental factors, could be passed on. This idea is linked to Lamarckism.

Lysenko argued that the idea of inheriting acquired traits was a major discovery. He said it was started by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and later used by Darwin. He claimed that Mendelian geneticists had rejected this important idea.

Works

- Heredity and its Variability (1945)

- The Science of Biology Today (1948)

- Agrobiology: Essays on Problems of Genetics, Plant Breeding and Seed Growing (1954)

Awards and Honors

- Hero of Socialist Labor (1945)

- Order of Lenin, eight times (1935, 1945, 1945, 1948, 1949, 1953, 1958, 1961)

- Medal "For Labour Valour" (1959)

- Jubilee Medal "In Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin" (1969)

- Medal "For Valiant Labour in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945)

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947)

- Stalin Prize, three times (1941, 1943, 1949)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labor of the Ukrainian SSR (1931)

- Gold Medal named after I.I. Mechnikov (1950)

Legacy

Some streets in the Soviet Union were named after Lysenko.

The writers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky said Lysenko inspired a character in their 1965 book Monday Begins on Saturday. They described the character as a demagogue (someone who gains power by appealing to emotions), ignorant, and rude. They said Lysenko destroyed Soviet biology and harmed many geneticists.

See also

In Spanish: Trofim Lysenko para niños

In Spanish: Trofim Lysenko para niños

- Agriculture in the Soviet Union

- Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

- VASKhNIL

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |