Thomas Hunt Morgan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Hunt Morgan

|

|

|---|---|

Johns Hopkins yearbook of 1891

|

|

| Born | September 25, 1866 |

| Died | December 4, 1945 (aged 79) |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American scientist. He was an evolutionary biologist, geneticist, and embryologist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933. This award was for his discoveries about how chromosomes carry genes and pass on traits.

Morgan earned his Ph.D. in zoology from Johns Hopkins University in 1890. He studied how living things develop at Bryn Mawr. After scientists rediscovered Mendelian inheritance in 1900, Morgan began studying the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster.

In his famous "Fly Room" at Columbia University, Morgan showed that genes are found on chromosomes. This proved how traits are passed down from parents to offspring. These discoveries created the foundation of modern genetics.

During his career, Morgan wrote 22 books and 370 scientific papers. His work made Drosophila a very important model organism in genetics. The Division of Biology he started at the California Institute of Technology later produced seven Nobel Prize winners.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Thomas Hunt Morgan was born in Lexington, Kentucky. His parents were Charlton Hunt Morgan and Ellen Key Howard Morgan. His family faced challenges after the American Civil War.

At age 16, Morgan started college at the State College of Kentucky. This school is now the University of Kentucky. He loved science, especially natural history. During summers, he worked with the United States Geological Survey. He graduated in 1886 with a Bachelor of Science degree.

After college, Morgan began studying zoology at Johns Hopkins University. He did experimental work on how sea spiders develop. He wanted to understand how they were related to other arthropods. He earned his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins in 1890.

From 1910 to 1925, Morgan and his team often moved their research to the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Morgan was also very involved in running the MBL for many years.

Career and Research Discoveries

Bryn Mawr College Work

In 1890, Morgan became a professor at Bryn Mawr College. He led the biology department there. He taught courses about the structure of living things. He also did a lot of research in his lab.

In 1894, Morgan traveled to Naples, Italy, to do research. There, he worked with German biologist Hans Driesch. Driesch's work on how organisms develop sparked Morgan's interest. Morgan began to change his focus from just describing organisms to doing experiments. He wanted to find physical and chemical reasons for how living things grow.

At that time, scientists debated how an embryo develops. Some thought that each part of an embryo was "set" from the start. Others, like Morgan and Driesch, believed that development could be influenced. Morgan's work showed that cells from sea urchin and ctenophore eggs could develop into complete larvae. This showed that development was more flexible than some believed.

Morgan also studied regeneration. This is how living things can regrow lost body parts. He studied this in tadpoles, fish, and earthworms. In 1897, he wrote his first book, The Development of the Frog's Egg. In 1901, he published Regeneration.

Columbia University and Fruit Flies

Morgan worked at Columbia University for 24 years, starting in 1904. Here, he focused on how traits are passed down and how living things change over time.

Around 1908, Morgan started working with the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. He encouraged his students to do the same. He tried to create changes, or mutations, in Drosophila using different methods. For two years, they didn't have much success.

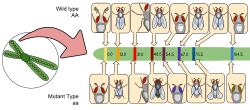

Then, in 1909, some new, heritable mutations appeared. In 1910, Morgan found a male fruit fly with white eyes among the normal red-eyed ones. When he bred this white-eyed male with a red-eyed female, all their offspring had red eyes. In the next generation, some males had white eyes again. This showed that the white-eye trait was linked to sex. Morgan realized this trait was carried on one of the sex chromosomes. He named the gene for this trait white.

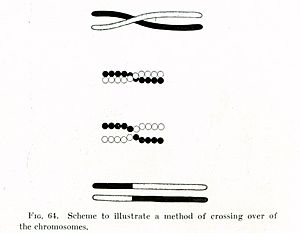

Morgan and his students found more mutant flies. They studied how thousands of fruit flies inherited different traits. They noticed that some genes, like the one for miniature wings and the white-eye gene, were on the same chromosome but sometimes separated. This led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and crossing over. He suggested that the amount of crossing over could show how far apart genes were on a chromosome.

Morgan's student, Alfred Sturtevant, used this idea to create the first genetic map in 1913. This map showed the order of genes on a chromosome.

In 1915, Morgan, Sturtevant, Calvin Bridges, and H. J. Muller wrote an important book. It was called The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity. This book became a key textbook for the new field of genetics. Most biologists soon accepted the idea that genes are on chromosomes.

Morgan's "fly-room" at Columbia became very famous. Many other labs around the world started studying fruit flies. Drosophila became one of the most important model organisms for genetic research.

Caltech and Later Years

In 1928, Morgan moved to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). He led the Division of Biology there until he retired in 1942. He wanted Caltech's program to focus on genetics, evolution, and experimental biology. He brought many talented scientists from Columbia to Caltech.

Morgan held many important positions in American science. He was President of the National Academy of Sciences from 1927 to 1931. In 1933, Morgan won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. He shared his prize money with his colleagues and children. This showed that he believed it was a team effort.

Even after retiring in 1942, Morgan continued his research. He kept working on questions about how organisms develop and regenerate.

Morgan and Evolution

Morgan was interested in evolution throughout his life. He wrote several books about it. Early in his career, he questioned Darwin's idea of natural selection. He didn't think small changes could create entirely new species.

However, after discovering many small, stable changes (mutations) in Drosophila, Morgan gradually changed his mind. He realized that only traits that are inherited can affect evolution. In his 1916 book, A Critique of the Theory of Evolution, Morgan explained the new science of Mendelian heredity. He concluded that evolution happens when helpful mutations are passed on.

Darwin's theory of natural selection needed a way to explain how traits were inherited. Morgan's work on genetics provided this missing piece. By creating the foundation of genetics, Morgan helped develop the modern understanding of evolution.

Awards and Honors

Thomas Hunt Morgan left a huge impact on the field of genetics. Some of his students later won their own Nobel Prizes.

- Johns Hopkins and the University of Kentucky gave him honorary degrees.

- He became a member of the Member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1909.

- He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1919.

- In 1924, Morgan received the Darwin Medal.

- The Thomas Hunt Morgan School of Biological Sciences at the University of Kentucky is named after him.

- The Genetics Society of America gives out the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal each year. This award honors scientists who have made major contributions to genetics.

- In 1989, a stamp in Sweden featured Morgan's discovery.

Personal Life

On June 4, 1904, Thomas Hunt Morgan married Lillian Vaughan Sampson. She was also a biology student. They had four children. Lillian later helped significantly with Morgan's Drosophila research. One of their children, Isabel Morgan, became a virologist who studied polio.

Death

Morgan had a long-term stomach problem. In 1945, at age 79, he had a severe heart attack and passed away.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Hunt Morgan para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Hunt Morgan para niños