Harry Blackmun facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harry Blackmun

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office June 9, 1970 – August 3, 1994 |

|

| Nominated by | Richard Nixon |

| Preceded by | Abe Fortas |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Breyer |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit | |

| In office September 21, 1959 – June 8, 1970 |

|

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | John B. Sanborn Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Donald Roe Ross |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Harry Andrew Blackmun

November 12, 1908 Nashville, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1999 (aged 90) Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

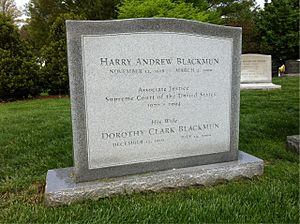

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Dorothy Clark

(m. 1941) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Harvard University (AB, LLB) |

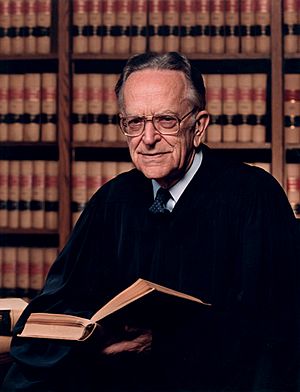

Harry Andrew Blackmun (November 12, 1908 – March 4, 1999) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994. An Associate Justice is one of the nine judges who make decisions in the highest court in the U.S. President Richard Nixon, a Republican, appointed Blackmun. Over time, Blackmun became known as one of the most liberal judges on the Court.

Blackmun grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota. He went to Harvard Law School and finished in 1932. He worked as a lawyer in Minnesota, even representing the famous Mayo Clinic. In 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower chose him to be a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Later, President Nixon nominated Blackmun for the Supreme Court. This happened after two other people Nixon chose were not approved. Blackmun was a close friend of Chief Justice Warren Burger. They were sometimes called the "Minnesota Twins" because they often voted the same way. However, Blackmun's views changed over time, and he started to disagree with Burger more often. He retired from the Court in 1994 and was replaced by Stephen Breyer.

Some important decisions Blackmun helped make include Bates v. State Bar of Arizona and Bigelow v. Commonwealth of Virginia. He also wrote opinions disagreeing with the majority in cases like Furman v. Georgia.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Harry Andrew Blackmun was born on November 12, 1908, in Nashville, Illinois. His parents were Theo Huegely (Reuter) and Corwin Manning Blackmun. He grew up in Dayton's Bluff, a working-class area in Saint Paul, Minnesota. His father owned a small store there. Harry went to the same grade school as his future colleague, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger. Blackmun was a Methodist.

He attended Mechanic Arts High School in Saint Paul. He graduated fourth in his class in 1925. He planned to go to the University of Minnesota. But he received a scholarship to Harvard University. He graduated from Harvard in 1929 with a degree in mathematics. At Harvard, he joined a fraternity and sang in the Harvard Glee Club. He even performed for President Herbert Hoover in 1929.

Blackmun then went to Harvard Law School. One of his teachers was future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter. He earned his law degree in 1932. After law school, Blackmun returned to Minnesota. He worked as a private lawyer and also taught law at local colleges. His law work often involved taxes and civil lawsuits. In 1941, he married Dorothy Clark, and they had three daughters. From 1950 to 1959, Blackmun worked as a lawyer for the Mayo Clinic. He later said this was "his happiest time."

Becoming a Judge

In the late 1950s, Blackmun's friend, Warren E. Burger, encouraged him to become a judge. Judge John B. Sanborn Jr. of the Eighth Circuit Court was planning to retire. He told Blackmun he would recommend him to President Eisenhower. After much encouragement, Blackmun agreed to accept the nomination.

On August 18, 1959, President Eisenhower nominated Blackmun. He was chosen for a seat on the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. The American Bar Association said he was "exceptionally well qualified." The United States Senate approved him on September 14, 1959. He officially became a judge on September 21. For the next ten years, Blackmun wrote 217 opinions for the Eighth Circuit. His time on this court ended on June 8, 1970. This was because he was appointed to the Supreme Court.

Serving on the Supreme Court

President Richard Nixon nominated Harry Blackmun to be an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on April 15, 1970. The U.S. Senate approved him on May 12 with a vote of 94–0. He took his oath of office on June 9, 1970. This was Nixon's third try to fill the spot. The spot became open when Justice Abe Fortas resigned in 1969. Nixon's first two choices were not approved by the Senate. It had been a very long time since a president had two Supreme Court nominees rejected. This was also the longest time the Court had a vacant seat since 1873.

While on the Supreme Court, Blackmun also served as a special judge for the Eighth Circuit. He did this from 1970 to 1994. He also briefly served for the First Circuit in 1990.

Starting Out on the Court

Blackmun was a lifelong Republican. People expected him to interpret the Constitution in a conservative way. The Chief Justice at the time, Warren Burger, was Blackmun's old friend. Burger had even recommended Blackmun to President Nixon. The two were often called the "Minnesota Twins." This was because they were both from Minnesota. It was also because they often voted the same way on cases. In his first five years (1970-1975), Blackmun voted with Burger almost 90% of the time. He voted with William J. Brennan, a leading liberal judge, only 13% of the time.

In 1972, Blackmun joined Burger and Nixon's other two appointees. They disagreed with the decision in Furman v. Georgia. This decision stopped all death penalty laws in the U.S. at that time. In 1976, Blackmun voted to bring back the death penalty in Gregg v. Georgia. He said that he personally disliked the death penalty. But he believed his personal feelings should not affect whether it was constitutional.

Changing Views

However, Blackmun's views began to change between 1975 and 1980. By then, he was voting with Justice Brennan more often. He was voting with Burger less often. After Blackmun disagreed with the majority in a case called Rizzo v. Goode (1976), a lawyer named William Kunstler welcomed him to the "liberals."

From 1981 to 1986, when Burger retired, Blackmun and Burger voted together much less often. Blackmun started to vote with Brennan much more often.

Later Years and Important Decisions

Blackmun began to move away from Burger's influence. He started to agree more with Justice Brennan. He believed the Constitution protected more individual rights. Burger and Blackmun's friendship became difficult over the years.

From 1981 to 1990, Blackmun voted with the most liberal judges, Brennan and Thurgood Marshall, almost all the time.

Even though Blackmun personally disliked the death penalty, he voted to uphold it in some cases early on. But on February 22, 1994, he announced a big change. He said he now believed the death penalty was always unconstitutional. He wrote a strong statement in a case called Callins v. Collins. He declared, "From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death." After this, he started to write a dissenting opinion (a statement of disagreement) in every death penalty case. He said he would always refer back to his Callins statement.

In another case, Herrera v. Collins (1993), the Court said prisoners could not always introduce new evidence of innocence to get federal help. Blackmun disagreed. He wrote that executing someone who is innocent "comes perilously close to simple murder."

Blackmun had several notable law clerks. These included Edward B. Foley and Chai Feldblum.

Relationships with Other Justices

When Blackmun's personal papers were released, some of his notes about fellow Justice Clarence Thomas became public. But Thomas spoke kindly of Blackmun at an event in 2001. He mentioned that Blackmun drove a blue Volkswagen Beetle. He also said Blackmun would tell people at fast food places that he was "Harry. I work for the government."

Blackmun and Justice Potter Stewart both loved baseball. One time, during an argument in court in 1973, Stewart passed Blackmun a note. It said, "V.P. AGNEW JUST RESIGNED!! METS 2 REDS 0." This was during an important baseball game. The Mets won that game and went to the 1973 World Series.

Life After the Court

Blackmun announced he was retiring from the Supreme Court in April 1994. He officially left on August 3, 1994. By this time, he was known as the Court's most liberal justice. President Bill Clinton nominated Stephen Breyer to take his place. The Senate approved Breyer.

In 1995, Blackmun received an award for great public service. It was called the United States Senator John Heinz Award.

In 1997, Blackmun played a judge in the Steven Spielberg movie Amistad. This made him the only U.S. Supreme Court justice to act as a judge in a movie!

On February 22, 1999, Blackmun fell at home and broke his hip. He had surgery the next day. But he never fully recovered. Ten days later, on March 4, he passed away at age 90. He died from problems after the surgery. His body was placed in the Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court Building. He was buried five days later at Arlington National Cemetery. His wife, Dorothy, passed away seven years later in 2006 at age 95. She was buried next to him.

In 2004, the Library of Congress released Blackmun's many files. He had saved documents from every case. He also kept notes that judges passed to each other. He even saved 10% of the mail he received. After he retired, Blackmun recorded a 38-hour oral history. In it, he talked about his thoughts on important cases and other things. Books like Becoming Justice Blackmun and Supreme Conflict used his papers.

See also

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2)

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Burger Court

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |