William J. Brennan Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William J. Brennan Jr.

|

|

|---|---|

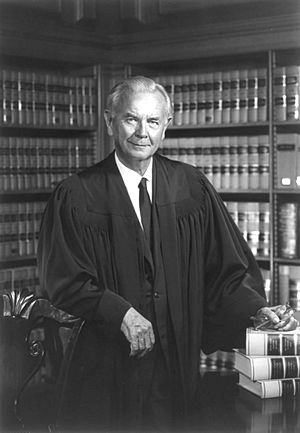

Official portrait, 1972

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 16, 1956 – July 20, 1990 |

|

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Sherman Minton |

| Succeeded by | David Souter |

| Associate Justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court | |

| In office April 1, 1951 – October 13, 1956 |

|

| Nominated by | Alfred E. Driscoll |

| Preceded by | Henry E. Ackerson Jr. |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Weintraub |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Joseph Brennan Jr.

April 25, 1906 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | July 24, 1997 (aged 91) Arlington, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | |

William Joseph Brennan Jr. (born April 25, 1906 – died July 24, 1997) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as a Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1956 to 1990. He was one of the longest-serving justices in the Supreme Court's history. Brennan was known for being a leader of the Court's liberal side.

Born in Newark, New Jersey, Brennan studied economics at the University of Pennsylvania. He then went to Harvard Law School. He worked as a lawyer in New Jersey and served in the U.S. Army during World War II. In 1951, he was appointed to the Supreme Court of New Jersey.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower chose Brennan for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1956. This happened just before the 1956 presidential election. Brennan was confirmed by the Senate the next year. He stayed on the Court until he retired in 1990. David Souter took his place.

On the Supreme Court, Brennan was known for his strong progressive ideas. He was against the death penalty. He also supported gay rights. He wrote important opinions in many cases. These included Baker v. Carr (1962), which said that how voting districts are drawn can be reviewed by courts. He also wrote New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). This case made it harder for public officials to win libel lawsuits.

Many people thought Brennan was one of the most important members of the Court. He was good at getting other justices to agree with his ideas. Justice Antonin Scalia even called him "probably the most influential Justice of the [20th] century."

Contents

Early Life and Education

William J. Brennan Jr. was born on April 25, 1906. He was the second of eight children. His parents, William and Agnes Brennan, were immigrants from Ireland. They both came from County Roscommon. His father, William Brennan Sr., worked as a metal polisher. He later became the Commissioner of Public Safety for Newark from 1927 to 1930.

Brennan went to public schools in Newark. He graduated from Barringer High School in 1924. He then studied economics at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. He graduated with honors in 1928. He was also part of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity. Brennan graduated from Harvard Law School in 1931. He was one of the top students in his class.

When he was 21, Brennan married Marjorie Leonard. They had met in high school. They had three children: William III, Nancy, and Hugh.

Early Legal Career

After law school, Brennan worked as a lawyer in New Jersey. He focused on labor law. During World War II, Brennan joined the Army in 1942. He started as a major and left as a colonel in 1945. He did legal work for the army's ordnance division.

In 1949, Governor Alfred E. Driscoll appointed Brennan to the Superior Court. This was a trial court in New Jersey. In 1951, Driscoll appointed him to the Supreme Court of New Jersey.

Serving on the Supreme Court

Becoming a Supreme Court Justice

President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Brennan to the associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on October 15, 1956. He was sworn in the next day. This happened just before the 1956 presidential election. Eisenhower's advisors thought appointing a Roman Catholic Democrat from the Northeast would help him win votes. Brennan was also strongly supported by Cardinal Francis Spellman.

Brennan caught the eye of Herbert Brownell, Eisenhower's chief legal advisor. Brennan gave a speech that seemed to show he had conservative views.

His appointment was formally sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee in January 1957. There was some debate about it. Some groups worried he would base his rulings on his religious beliefs instead of the Constitution. Senator Joseph McCarthy also criticized Brennan for calling some anti-Communist investigations "witch-hunts." Brennan defended himself at his hearing. He said he would rule only based on the Constitution. He was confirmed by almost all senators, with only Senator McCarthy voting no.

Brennan was the first state court judge appointed to the Supreme Court since 1932. Eisenhower also wanted to show he was fair by appointing someone from the other political party. Brennan took the seat left empty by Justice Sherman Minton. He served until he retired on July 20, 1990, due to health reasons. Justice David Souter replaced him. Brennan was the last federal judge appointed by President Eisenhower to still be serving. After retiring, he taught at Georgetown University Law Center until 1994. He wrote 1,360 opinions during his time on the Court.

The Warren Court Years

Brennan was a strong liberal throughout his career. He played a key role in the Warren Court's efforts to expand individual rights. He worked behind the scenes to convince more conservative justices to join the Court's decisions.

Brennan wrote important opinions during the Warren Era. These included cases about voting rights (Baker v. Carr), criminal procedures (Malloy v. Hogan), and civil rights (Green v. County School Board of New Kent County). He was especially important in expanding free speech rights under the First Amendment. He wrote the Court's opinion in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). This case set new rules for libel lawsuits. Brennan also created the phrase "chilling effect" in a 1965 case. His close friendship with Chief Justice Warren led other justices to call him the "deputy Chief."

Later Courts: Burger and Rehnquist

On the less liberal Burger Court, Brennan strongly opposed the death penalty. He joined the majority in a major ruling on this issue (Furman v. Georgia (1972)). As the Court became more conservative, especially with William Rehnquist becoming Chief Justice, Brennan often found himself alone. Sometimes, only Justice Thurgood Marshall would agree with him. By 1975, they were the last liberals from the Warren Court. Their close views led their law clerks to call them "Justice Brennan-Marshall."

Brennan believed the death penalty was always "cruel and unusual punishment." He and Marshall disagreed with every decision that upheld the death penalty. No other justice agreed with this view for many years. However, Justice Harry Blackmun eventually agreed in 1994, after Brennan had retired.

Brennan wrote Supreme Court opinions that said people could sue the government for money if their rights under the Bill of Rights were violated. For example, in Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, he said this applied to the Unreasonable Search and Seizure clause of the Fourth Amendment.

In his last years on the Court, Brennan wrote important rulings about flag burning. In Texas v. Johnson and United States v. Eichman, the Court said that burning the U.S. flag is a form of free speech protected by the First Amendment.

Brennan's first wife, Marjorie, died in 1982. A few months later, in March 1983, he married Mary Fowler. She had been his secretary for 26 years.

Brennan's Judicial Ideas

Brennan strongly believed in the Bill of Rights. He argued that it should apply to state governments as well as the federal government. He often supported individual rights against the government. He favored criminal defendants, minorities, and other groups who were not always well-represented. He was also willing to compromise to get a majority of justices to agree with him.

Some critics said Brennan was too much of a "judicial activist." They claimed he decided what outcome he wanted first, then found legal reasons for it. When he retired, Brennan said the most important case he worked on was Goldberg v. Kelly. This case ruled that the government could not stop welfare payments without first holding a hearing.

In the 1980s, the Reagan administration and the Rehnquist Court tried to change some of the Warren Court's decisions. Brennan spoke out more about his views. In a 1985 speech, he criticized the idea of interpreting the Constitution only by its original meaning. He said the Constitution should be read to protect "human dignity" in modern times.

Brennan was very firm in his opposition to the death penalty. He believed that the state taking a human life as punishment was always cruel and unusual. He and Thurgood Marshall believed the death penalty was unconstitutional in all cases. They never accepted the ruling in Gregg v. Georgia, which said the death penalty was constitutional. After that, Brennan and Marshall always wrote dissenting opinions in death penalty cases.

Brennan also wrote a dissenting opinion in Glass v. Louisiana. In this case, the Court chose not to hear a challenge to using the electric chair for executions. Brennan said that electrocution was like "burning people at the stake."

Brennan supported gay rights. He wrote that "Homosexuals have historically been the object of deep and sustained pernicious hostility." He believed that discrimination against gay people was based on prejudice, not logic. He is seen as one of the most liberal justices in the history of the Supreme Court.

Famous Quotes

Here are some of William Brennan's famous quotes:

- "We current Justices read the Constitution in the only way that we can: as twentieth century Americans. We look to the history of the time of framing and to the intervening history of interpretation. But the ultimate question must be, what do the words of the text mean in our time. For the genius of the Constitution rests not in any static meaning it might have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems and current needs."

- "The dissemination of ideas can accomplish nothing if otherwise willing addressees are not free to receive and consider them. It would be a barren marketplace of ideas that had only sellers and no buyers." Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 (1965) (concurring).

- "[W]e consider this case against the background of a profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials." New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964).

- "I cannot accept the notion that lawyers are one of the punishments a person receives merely for being accused of a crime." Jones v. Barnes, 463 U.S. 745, 764 (1983) (dissenting).

- "If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child." Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).

- "We do not consecrate the flag by punishing its desecration, for in doing so we dilute the freedom that this cherished emblem represents." Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989).

Honors and Awards

William Brennan received many awards for his long career on the Supreme Court.

- In 1969, he received the Laetare Medal from the University of Notre Dame. This is a very important award for American Catholics.

- In 1987, he received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Public Service.

- In 1989, a historic courthouse in Jersey City, New Jersey, was renamed the William J. Brennan Court House in his honor. He also received the Freedom Medal that year.

- On November 30, 1993, President Bill Clinton gave Brennan the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is one of the highest civilian awards in the U.S.

When he died, Brennan's body lay in repose in the Great Hall of the United States Supreme Court Building. This is a special honor.

Years later, in 2010, Brennan was added to the New Jersey Hall of Fame. William J. Brennan High School was founded in San Antonio, Texas, in his honor. Brennan Park in Newark, New Jersey, was also named after him. A statue of him was placed in front of the Essex County Hall of Records.

Images for kids

See also

- Brennan Center for Justice

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |