New York Times Co. v. Sullivan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The New York Times Co. v. Sullivan |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued January 6, 1964 Decided March 9, 1964 |

|

| Full case name | The New York Times Company v. L. B. Sullivan |

| Citations | 376 U.S. 254 (more)

84 S. Ct. 710; 11 L. Ed. 2d 686; 1964 U.S. LEXIS 1655; 95 A.L.R.2d 1412; 1 Media L. Rep. 1527

|

| Prior history | Judgment for plaintiff, Circuit Court, Montgomery County, Alabama; motion for new trial denied, Circuit Court, Montgomery County; affirmed, 144 So. 2d 25 (Ala. 1962); cert. granted, 371 U.S. 946 (1963). |

| Holding | |

| A newspaper cannot be held liable for making false defamatory statements about the official conduct of a public official unless the statements were made with actual malice. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Brennan, joined by Warren, Clark, Harlan, Stewart, White |

| Concurrence | Black, joined by Douglas |

| Concurrence | Goldberg, joined by Douglas |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amends. I, XIV | |

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan was a very important decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964. This case changed how freedom of speech and freedom of the press work in the United States. It made it harder for public officials to sue news organizations for defamation.

Defamation means saying or writing something false that harms someone's reputation. Before this case, it was easier to sue for defamation. But the Court decided that public officials need to prove something extra. They must show that the false statement was made with "actual malice". This means the person who made the statement either knew it was false or didn't care if it was true or false.

This ruling was very important for news organizations. It helped them report freely on important events, like the Civil Rights Movement. It protected them from many lawsuits that tried to stop them from sharing news.

Contents

What Happened in the Case?

The Advertisement that Started It All

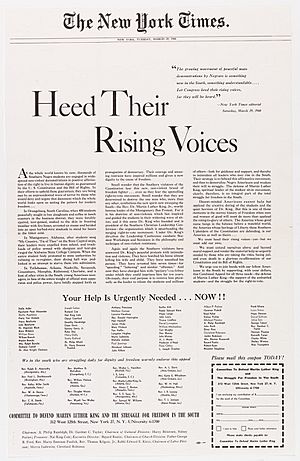

In 1960, The New York Times newspaper published a full-page advertisement. Supporters of Martin Luther King Jr. paid for it. The ad criticized the police in Montgomery, Alabama, for how they treated civil rights protesters.

The advertisement had some small mistakes. For example, it said King was arrested seven times, but he was arrested four times. It also described police actions around a college campus differently from what actually happened.

The Lawsuit Against the Times

L. B. Sullivan was the police commissioner in Montgomery. Even though the ad didn't name him, he felt it criticized him. He sued The New York Times for defamation in a local Alabama court.

The judge said the ad's mistakes were defamatory. A jury then decided that Sullivan was right and awarded him $500,000. This was a lot of money back then!

The New York Times appealed this decision. First, they went to the Supreme Court of Alabama, which agreed with the local court. Then, the Times asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear their case. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed because the case involved important questions about free speech.

Why the Times Didn't Retract for Sullivan

Under Alabama law, Sullivan had to ask for a public retraction first. The Times did not publish a retraction for Sullivan. Their lawyers said they were confused about how the ad reflected on him.

However, the Times later published a retraction for the Governor of Alabama. He also said the ad criticized him. The Secretary of the Times explained they retracted for the Governor because he represented the state. They also felt the ad referred to state authorities. But the Secretary still didn't think the ad referred to Mr. Sullivan.

Sullivan then filed his lawsuit. He also sued four African-American ministers who were mentioned in the ad.

The Supreme Court's Decision

A Unanimous Ruling

On March 9, 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court made its decision. All nine justices voted in favor of The New York Times. They said the Alabama court's decision went against the First Amendment.

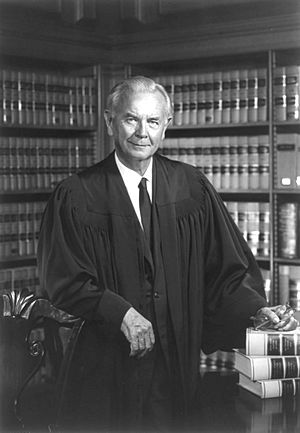

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote the main opinion for the Court. He explained that criticizing the government and public officials is a key part of American freedom of speech and press. He said that open discussion on public issues is very important. This discussion should be "uninhibited, robust, and wide-open." It might even include strong attacks on government officials.

Protecting Honest Mistakes

The Court understood that sometimes, people make mistakes when discussing public issues. They said that "erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate." This means that mistakes must be protected so that freedom of expression can truly exist.

Because of this, the Court decided that public officials suing for defamation must prove "actual malice." This means they must show that the false statement was made:

- With knowledge that it was false, OR

- With reckless disregard for whether it was false or not.

The Court also added two more rules for these types of lawsuits:

- The public official must prove the statement was about them personally, not just about government policy in general.

- The public official must prove the statement was false. In many other defamation cases, the person who made the statement has to prove it was true.

This decision made it much harder for public officials to win defamation lawsuits. It helped protect the ability of the press to report on important issues without fear of being sued for every small mistake.

How the Decision is Seen Today

A Landmark for Press Freedom

In 2014, on the 50th anniversary of the ruling, The New York Times newspaper wrote an editorial. They called the Sullivan decision "the clearest and most forceful defense of press freedom in American history."

The editorial said the ruling was revolutionary. It rejected almost any attempt to stop criticism of public officials, even if it was false. This was seen as central to the meaning of the First Amendment.

The Times also noted that today, with the internet, everyone can publish information. This means people can quickly call officials to account. But it also means reputations can be harmed quickly. The core ideas of the Sullivan case remain important.

Opinions from Legal Experts

In 2015, TIME Magazine surveyed over 50 law professors. Many of them called New York Times v. Sullivan one of the best Supreme Court decisions since 1960.

One professor said the decision helped strengthen "the free-speech traditions that have ensured the vibrancy of American democracy." Another said it made it much easier for citizens and the press to criticize powerful people.

Later Important Cases

The Sullivan decision led to other important rulings that built on its ideas:

- Curtis Publishing Co. v. Butts (1967): This case said that "public figures" (like celebrities or famous athletes) also need to prove "actual malice" if they sue news organizations for defamation.

- Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974): This case clarified that private people (not public officials or figures) do not need to prove "actual malice." They only need to show that the false statement was made carelessly (with negligence).

- Time, Inc. v. Hill (1967): The "actual malice" rule was also applied to cases about "false light" invasion of privacy. This is when someone is portrayed in a misleading way.

Recent Discussions About the Ruling

In recent years, some judges and legal experts have discussed whether the New York Times v. Sullivan decision should be changed.

For example, in 2019, Justice Clarence Thomas of the Supreme Court suggested that the Sullivan decision might have been wrong. He believes the Constitution might not require public officials to prove "actual malice."

In 2021, a federal judge named Laurence Silberman also called for the Supreme Court to overturn the Sullivan ruling. He argued that some major news outlets are too biased. These discussions show that the Sullivan decision, while very important, continues to be debated today.

See also

In Spanish: New York Times contra Sullivan para niños

In Spanish: New York Times contra Sullivan para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |