Sherman Minton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sherman Minton

|

|

|---|---|

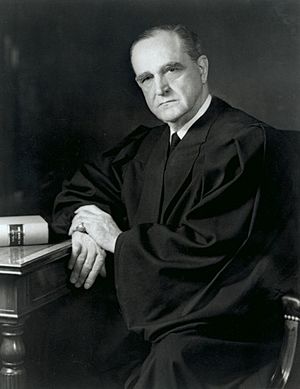

Official portrait, 1954

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office October 12, 1949 – October 15, 1956 |

|

| Nominated by | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Wiley Rutledge |

| Succeeded by | William J. Brennan Jr. |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit | |

| In office May 22, 1941 – October 11, 1949 |

|

| Nominated by | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Walter Emanuel Treanor |

| Succeeded by | Walter C. Lindley |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

| In office July 22, 1937 – January 3, 1941 |

|

| Leader | Alben W. Barkley |

| Preceded by | J. Hamilton Lewis |

| Succeeded by | J. Lister Hill |

| United States Senator from Indiana |

|

| In office January 3, 1935 – January 3, 1941 |

|

| Preceded by | Arthur Raymond Robinson |

| Succeeded by | Raymond E. Willis |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Sherman Minton

October 20, 1890 Georgetown, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | April 9, 1965 (aged 74) New Albany, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Gertrude Gurtz

(m. 1917) |

| Children | 3, including Sherman Jr. |

| Education | Indiana University Bloomington (BA) Indiana University Maurer School of Law (LLB) Yale University (LLM) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars | |

Sherman "Shay" Minton (born October 20, 1890 – died April 9, 1965) was an important American politician and judge. He served as a U.S. Senator for Indiana. Later, he became an Associate Justice on the highest court in the United States. He was a member of the Democratic Party.

After finishing college and law school, Minton fought as a captain in World War I. When he returned, he started a career in law and politics. In 1930, he became a utility commissioner in Indiana. Four years later, Minton was elected to the United States Senate. During his campaign, he strongly supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs. He even gave a famous speech called "You Cannot Eat the Constitution," saying that helping people during the Great Depression was more important than strict rules.

After losing his Senate re-election in 1940, President Roosevelt appointed him as a federal judge for the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. After Roosevelt passed away, President Harry S. Truman, who was Minton's friend, nominated him to the Supreme Court. He joined the Court on October 12, 1949, and served for seven years. Minton believed that judges should not overturn laws unless they were clearly against the Constitution. He retired in 1956 due to poor health. He passed away in 1965.

Historians say Minton's way of thinking as a judge was shaped by how the Supreme Court had stopped many New Deal laws. He believed the Court should let the other parts of the government (Congress and the President) do their jobs. He usually supported laws passed by Congress. This was interesting because he was a strong supporter of liberal ideas as a Senator, but a more careful judge. He often helped bring peace among the judges during a time when the Court had many disagreements. In 1962, the Sherman Minton Bridge was named after him in Indiana.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Growing Up in Indiana

Sherman Minton was born on October 20, 1890, in Georgetown, Indiana. He was the third of five children. His family called him "Shay" because his younger brother couldn't say "Sherman" properly.

Sherman went to a small, two-room school in Georgetown until eighth grade. His father often took him to political events, which sparked his interest in politics early on. His father worked for the railroad but became disabled in 1898. This made the family very poor. In 1900, his mother passed away during a surgery. This was very hard for Minton, and he became angry with God.

When he was 14, in 1904, Minton was arrested for riding his bicycle on the sidewalk. He had to pay a fine. This event made him want to become a lawyer. To help his family and save money for school, he went to Fort Worth, Texas, with his older brother to work at a meatpacking plant. After his family joined him and settled, Minton returned to Indiana for high school.

School Days

Minton started Edwardsville High School in 1905. The next year, his school joined with New Albany High School. He was very active, playing football, baseball, and track. He also started the school's first debate club, which won many awards. He worked at a local arcade and went back to Texas in the summers to work.

He was briefly kicked out of school in 1908 for a prank. But the school's superintendent, Charles A. Prosser, let him return after he apologized to the whole school. Minton graduated at the top of his class in 1910.

He wanted to go to college. In 1910, he worked as a salesman to earn money. In September 1911, he started at Indiana University Bloomington. He took many classes, finishing three years of work in two years. He also played baseball and joined the debate team. He became friends with many people who would later become important in Indiana politics. During his second year, he ran out of money and had to live very simply, eating wild berries and leftover bread. He graduated from college at the top of his class in 1913.

In 1915, he graduated from the Indiana University School of Law. He played football there too. He was first in his law class, which earned him a scholarship to Yale Law School. At Yale, he studied constitutional law and learned from former President William Howard Taft. Minton earned a Master of Laws degree. Taft said Minton's thesis was one of the best he had ever read. Minton also improved his public speaking and helped start a legal aid society at Yale.

Becoming a Lawyer and Serving in World War I

In May 1916, Minton opened his own law office in New Albany. He took on many cases, some for free, to help the local prosecutor. He also traveled and gave speeches. During one trip, he met William Jennings Bryan, who encouraged him to think about a career in public service.

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, Minton joined the United States Army. He trained to become an officer and was commissioned as a captain. Before he left, he married Gertrude Gurtz on August 11. Minton's unit went to France in July 1918. They served on the Western Front at Verdun and Soissons. His unit mostly scouted roads to make sure supplies could reach the front lines safely. He did not see direct combat.

After the war ended, Minton stayed in Paris for several months to study law at the University of Paris. He returned home in March 1920. His first child, Sherman Jr., was born while he was away. His daughter Mary-Anne was born in 1923, and his second son, John, in 1925.

Political Career

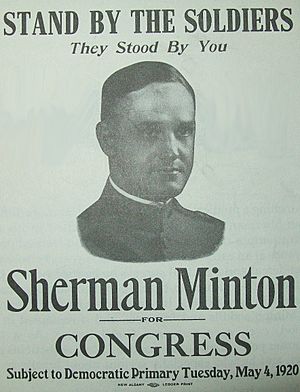

When Minton came home, he started his law practice again and decided to enter politics. He ran for Congress in 1920 but lost. He tried again in 1930 and lost again.

In 1931, Minton became a local leader of the American Legion, a group for veterans. He used this position to support the Democratic Party. When his friend Paul McNutt became governor of Indiana in 1930, he offered Minton a job leading a new utility commission. In this role, Minton successfully lowered state telephone bills, which made him popular.

Running for Senate

Because he was popular, party leaders encouraged Minton to run for the United States Senate in 1934. With Governor McNutt's help, Minton won the Democratic nomination.

Minton started campaigning in August 1934. He strongly defended President Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs, which aimed to help the country recover from the Great Depression. He blamed Republicans for the country's problems. His opponent, Senator Arthur Raymond Robinson, criticized Minton's support for the New Deal.

Minton famously said, "You can't offer a hungry man the Constitution." He meant that during a crisis like the Great Depression, people's urgent needs were more important than strict interpretations of the Constitution. This speech was very controversial, and many people criticized him. Minton stopped using the slogan, but his opponents kept bringing it up. Despite the criticism, Minton won the election with 52 percent of the vote.

Serving in the Senate

Minton became a Senator in January 1935. He quickly became friends with fellow new Senator Harry S. Truman. Minton was known for being a strong supporter of his party. He often argued fiercely with his opponents.

Minton was part of a special committee that looked into lobbyist groups. He believed some media owners were unfairly attacking the New Deal. He even tried to pass a law that would make it illegal to publish "information known to be false." But other politicians worried this would limit freedom of the press, so he dropped the idea.

Court Packing Plan

In 1936, the Supreme Court ruled that some New Deal laws were unconstitutional. Minton believed the Court was letting politics influence its decisions. President Roosevelt then proposed a plan to add more justices to the Supreme Court. This would allow him to appoint judges who supported his New Deal programs.

Minton strongly supported Roosevelt's plan. He became a leading voice for it in the Senate. His support helped him become the Senate Majority Whip, a role that helped him push for the bill. Minton gave many speeches to convince people to support the plan. However, many Democrats, fearing for their own re-election, joined Republicans to defeat the bill. Minton was disappointed, but his strong support for the President made him more influential within his party.

Even though Minton usually supported Roosevelt, he sometimes disagreed. He voted to give bonus pay to World War I soldiers, even though Roosevelt had vetoed it. He also supported an anti-lynching bill, which Roosevelt worried would upset Southern states.

As World War II approached, Minton was careful about the United States getting involved. He believed America would eventually join the war but wanted to delay it as long as possible. He supported expanding the American military. He also voted for the Smith Act, which made it a crime to advocate overthrowing the government, targeting communists and fascists.

Re-election and New Role

Minton ran for re-election to the Senate in 1940. This was a tough election because the Republican presidential candidate, Wendell Willkie, was also from Indiana. Minton lost the election by a small number of votes.

After leaving the Senate in January 1941, President Roosevelt gave Minton a job as an adviser. He helped connect the White House with Congress. He also helped many people get appointed to government jobs. He even convinced Roosevelt to support creating a Senate defense committee led by his friend, Harry Truman. This helped Truman become more well-known and eventually become Vice President.

Seventh Circuit Court Judge

Becoming a Judge

On May 7, 1941, President Roosevelt nominated Minton to be a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago. The Senate quickly approved him. Minton took his oath of office on May 29, 1941.

The Seventh Circuit Court was very busy, handling many cases each year. Minton became good friends with Judge J. Earl Major, who shared his ideas about law. They often went to baseball games together.

When World War II started, the court had many new types of cases. These included challenges to wartime rules, draft laws, and price controls. Minton usually supported the decisions made by the lower courts. He believed that the first court to hear a case was usually best at making a decision.

Minton's Approach to Law

Minton was known for believing in "judicial restraint." This means he thought judges should limit their own power and not overturn laws unless they clearly went against the Constitution. This was a change from his time as a Senator, where he was very political. He developed this view because he disliked how courts had overturned laws he helped create in the Senate.

During his time on the Seventh Circuit, Minton wrote 253 opinions. People praised his opinions on tax law, calling them "direct Hoosier logic." They said he could explain complex issues in a simple way.

In one important case, United States v. Knauer, the government stopped a U.S. citizen's wife from entering the country because of possible ties to Nazism. Minton agreed with the decision, saying that whether a non-citizen could enter was a political decision, not a legal right.

Minton often said he had to "pronounce the law as it was written, but on no occasion [c]ould he make the law." This shows his belief that judges should follow the law, not create new ones.

Health Challenges

After President Roosevelt died, President Truman asked Minton to lead the War Department Clemency Board. This board reviewed decisions made by military courts. This extra work, along with his court duties, made Minton very busy and affected his health.

In September 1945, Minton had a heart attack and was in the hospital for three months. He also suffered from anemia, which made him tired. In 1949, he broke his leg and had to use a cane for the rest of his life. These health issues made him want a less demanding job. He told Truman he would be interested in a seat on the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Justice

Becoming a Supreme Court Justice

On September 15, 1949, President Truman announced that he was nominating Minton to the Supreme Court. Truman praised Minton's legal education and experience as a judge.

The news of Minton's nomination received mixed reactions. Some newspapers said Truman was letting friendship influence his choice. Others pointed out Minton's strong qualifications.

Some Senators tried to make Minton appear for a hearing, but he refused. He said his broken leg made travel difficult. He also argued that as a sitting judge and former Senator, it would be improper for him to be questioned. The Senate Judiciary Committee approved his nomination, and the full Senate confirmed him on October 4, 1949, by a vote of 48 to 16. He was sworn into office on October 12. Sherman Minton is the only person from Indiana to serve on the Supreme Court. He is also the last person who was a member of Congress to be appointed to the Court.

Minton's Judicial Philosophy

Minton's main belief as a judge was to understand and follow the original meaning of laws. He thought the government should have broad powers. This was clear when he disagreed with the Court's decision in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. In this case, the Court said President Truman could not take control of steel mills during a strike without Congress's approval. Minton strongly believed the President should have that power to protect the nation.

Minton was against racial segregation. He voted with the majority in the famous 1954 case of Brown v. Board of Education, which ended segregation in schools. This was one of the few times he voted against the government.

When it came to civil liberties, Minton believed that rights like free speech were not absolute. They could be limited if they harmed others' rights. He also voted to support anti-communist laws during the "Red Scare" period. He often voted to allow government loyalty tests for employees.

Many people who supported liberal ideas were disappointed with Minton. They expected him to vote for more individual freedoms, but he often chose to support order and government power. However, historians like Linda Gugin say Minton was very committed to his belief in judicial restraint, meaning judges should stick to the law and not try to change society.

Later Years on the Court

Minton didn't enjoy his role as much in his later years on the Court. He was often in the minority when votes were taken. After some other judges passed away, Minton felt he had less support for his opinions. This made him think about retiring.

Despite disagreements among the judges, Minton was well-liked by his colleagues. He often acted as a peacemaker during a time when there were many personal feuds between strong personalities on the Court.

Minton told President Dwight D. Eisenhower he would retire on September 7, 1956. He said his health made his duties too difficult. His anemia had gotten worse, slowing him down. He retired on October 15, 1956, after serving for seven years. William J. Brennan Jr. took his place.

Later Life and Legacy

Retirement Years

After retiring, Minton returned to his home in New Albany. He took on a much lighter workload. He gave occasional lectures at Indiana University and made public speeches. For several years, he sometimes served as a temporary judge on lower federal courts. He received honorary degrees from the University of Louisville and Oxford University in England.

Even with his health problems, Minton remained active in the Democratic Party. He stayed in touch with his friend, former President Truman, and they met at party events.

Death and Honors

In late March 1965, Minton was admitted to the hospital and passed away on April 9. His funeral was attended by many important people, including Supreme Court justices and governors. He was buried in Holy Trinity Cemetery in New Albany.

Minton is remembered in several ways. The Sherman Minton Bridge, which connects Indiana and Kentucky over the Ohio River, is named after him. He attended its dedication ceremony in 1962. There is also an annual Sherman Minton Moot Court Competition at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law. The Minton-Capehart Federal Building in Indianapolis is also named in his honor. A bronze bust of Minton is displayed in the Indiana Statehouse.

Some historians praise Minton's clear legal thinking, but note that his decisions didn't have a big long-term impact. Other historians, like Bernard Schwartz, have a more negative view, saying his opinions were not very strong. Most of the legal ideas Minton supported were later changed by the Court after he retired.

Minton's time on the Court marked a change. After him, judges tended to serve longer terms. He was also the last member of Congress to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Some people believe that the courts have lost a valuable perspective by not having experienced lawmakers among their judges.

Minton played an important role behind the scenes, helping to keep peace between the different groups of judges. Justice Felix Frankfurter said that while Minton might not be remembered as a "great justice," he would be remembered as a "great colleague" by his fellow judges.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Sherman Minton para niños

In Spanish: Sherman Minton para niños

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |