Freedom of speech in the United States facts for kids

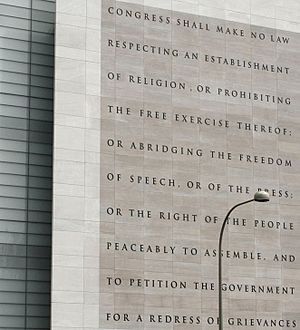

In the United States, people have the right to speak and express themselves. This right is strongly protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, state laws, and state constitutions. Freedom of speech means you can share your opinions publicly without the government stopping you. It includes deciding what to say and what not to say.

The Supreme Court of the United States has said that some types of speech have less protection. Also, governments can set fair rules about the time, place, and manner of speech. The First Amendment stops only government limits on speech. It does not stop private people or businesses from setting their own rules, unless they are acting for the government. However, some laws might stop private businesses from limiting what their employees say. For example, they can't stop workers from talking about their salary or forming a union.

The First Amendment protects your right to speak and to get information. It also stops the government from treating speakers differently. It limits how much people can be sued for what they say. And it stops the government from forcing people or companies to say or pay for speech they don't agree with.

Some types of speech are not fully protected by the First Amendment. These include obscene speech (very offensive content), fraud (lying to trick people), speech that is part of illegal actions, and speech that encourages immediate violence. Rules also apply to advertising (commercial speech). Other limits balance free speech with other rights. These include copyright (protecting authors' works), stopping threats of violence, and preventing lies that harm others (slander and libel). When a speech rule is challenged in court, it is usually seen as wrong. The government must then prove the rule is fair and follows the Constitution.

Contents

History of Free Speech

Early Days in England

Long ago, when America was still a group of colonies, England had strict rules about speech. It was a crime to criticize the government. This was called "seditious libel." A judge in 1704 said this rule was needed so people would have a good opinion of the government. It didn't matter if what you said was true; criticizing the government was still a crime. Before 1694, no one could publish anything without the government's permission.

Speech in the Colonies

The American colonies had different ideas about free speech. There were fewer "seditious libel" cases than in England. But other ways were used to control speech that disagreed with the government.

The strictest rules in the colonies were against speech seen as religiously offensive, or "blasphemous." For example, a 1646 Massachusetts law punished people who denied that the soul lives forever. In 1612, a Virginia governor set punishments for denying the Trinity. His laws also banned blasphemy and speaking badly about ministers or royalty.

Later studies show that from 1607 to 1700, colonists gained more freedom of speech. This helped set the stage for the American Revolution.

The trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735 was a big moment. Zenger was accused of seditious libel for criticizing New York's Governor. His lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, argued that truth should be a defense. The court disagreed, but the jury still found Zenger not guilty. This case was a victory for free speech. It showed that juries could ignore unfair laws. It also started a trend of more acceptance for free speech.

The First Amendment is Added

After the American Revolutionary War in the 1780s, people debated the new Constitution. Some, like Alexander Hamilton, wanted a strong federal government (Federalists). Others, like Thomas Jefferson, wanted a weaker federal government (Anti-Federalists).

Anti-Federalists worried the new Constitution gave too much power to the federal government. To address these worries, the Bill of Rights was created and added to the Constitution. The First Amendment was a big part of this. It limited the power of the federal government.

Alien and Sedition Acts

In 1798, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. These laws made it illegal to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writings" against the U.S. government or its leaders. The laws said that truth could be a defense, and you had to prove bad intentions.

These laws were controversial. Some members of Congress who supported the First Amendment also voted for these Acts. President John Adams's party, the Federalists, used these laws against their rivals. The Acts became a major issue in the 1800 election. After Thomas Jefferson became President, he pardoned those who had been convicted. The laws expired, and the Supreme Court never decided if they were constitutional.

Later, in 1964, the Supreme Court said that "the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history." This means the Sedition Act is now seen as a bad example of limiting speech.

Censorship in the Past

From the late 1800s to the mid-1900s, many laws limited speech. These limits were based on what society thought was right at the time. For example, Anthony Comstock pushed for laws against speech that offended Victorian morals. He helped create groups to stop "offensive" content.

City and state governments watched newspapers, books, theater, comedy, and films. They arrested people, seized materials, and gave fines. The Comstock laws stopped people from sending "banned" topics through the mail. Movies also had their own rules, like the Motion Picture Production Code (1930-1968). Comic books had the Comics Code Authority (1954-2011).

Some laws were for national security. During World War II, the Office of Censorship stopped military information from being shared. This included journalists' reports and all mail going in or out of the U.S. In the 1940s and 1950s, during McCarthyism, speaking in favor of Communism was suppressed. This led to the Hollywood blacklist and some arrests under the Smith Act.

Modern View of Free Speech

In the mid-to-late 1900s, the Supreme Court started to protect free speech more strongly. Now, freedom of speech is generally protected unless there's a clear reason not to. This means the government usually cannot control the content of what people say.

In 1971, Justice John Marshall Harlan II said the First Amendment protects a "marketplace of ideas." This means different ideas can be shared and debated. In 1972, Justice Thurgood Marshall explained that the government cannot stop expression because of its message or ideas. He said people have the right to express any thought without government censorship.

Types of Speech

Political Speech

This is the most protected type of speech. It's about expressing political ideas and is very important for a working democracy. Rules that limit political speech are usually very hard for the government to justify. One exception is rules about elections themselves. For example, rules about who can vote or run for office are allowed.

Commercial Speech

Commercial speech is speech that "suggests a business deal." This includes advertising. It is also protected by the First Amendment, but not as much as political speech. The government can put some limits on commercial speech. For example, it can stop false advertising.

Expressive Conduct

Expressive conduct is also called "symbolic speech." It means using actions, not just words, to share a message. Examples include:

- Burning a flag as a protest.

- Wearing armbands with symbols.

- Silent marches to make a point.

- Computer code or scientific formulas that express ideas.

Federal courts say that expressive conduct is protected by the First Amendment. But whether an action is protected can depend on why it was done. For example, burning a flag as a protest is protected. Burning a flag just to destroy property might not be.

Vague and Meaningless Speech

Some expressions don't have a clear or intended meaning. This includes instrumental music, abstract art, or even nonsense poems. These are generally protected as "speech." The Supreme Court has said that art by Jackson Pollock and the poem "Jabberwocky" are protected. This is different from places like Nazi Germany, which banned "degenerate art" and "degenerate music."

Courts have also protected artistic elements mixed with non-speech items. For example, a car painted as art. But the government can still have rules about where these things are displayed.

Types of Speech Restrictions

The Supreme Court has different ways of looking at laws that limit speech.

Content-Based Restrictions

These rules limit speech based on what is being said. They are usually seen as unconstitutional. This is true even if the government has a good reason or doesn't mean to be unfair. Rules that require checking the content of speech are very hard to justify.

Content-based rules can limit speech based on the subject or the viewpoint. For example, a city rule that bans all protests in front of a school, except for labor protests, is a subject-matter rule. It favors one topic over another. Rules that target specific viewpoints (e.g., only allowing pro-government speech) are almost always overturned. The Supreme Court has said that government money cannot be used to discriminate against a specific viewpoint.

To tell if a rule is content-based, ask if the speaker could have given a different message under the exact same conditions. If the rule would still apply, it might be content-neutral.

Time, Place, and Manner Restrictions

These rules control when, where, and how speech can happen. They don't control what is said. For example, you can't protest loudly in front of someone's house in the middle of the night. Or sit in the middle of a busy road during rush hour. These actions would cause problems for others.

To be allowed, time, place, and manner rules must:

- Be content neutral: They apply to everyone, no matter their message.

- Be narrowly tailored: They are specific and don't limit more speech than needed.

- Serve a significant government interest: They protect something important, like public safety or peace.

- Leave open ample alternative channels for communication: People must still have other ways to share their message. For example, they could protest on the sidewalk at a different time.

Sometimes, free speech is limited to "free speech zones." These are special areas for protests. Some people don't like these zones. They believe the First Amendment means the whole country is a free speech zone. Many civil rights groups say these zones are used to hide protests from the public.

The Supreme Court has said that while free speech is a basic right, it doesn't mean you can speak anywhere, anytime. In 1965, the Court said, "The rights of free speech and assembly... do not mean that everyone... may address a group at any public place and at any time."

Public Forum Doctrine

Time, place, and manner rules are often linked to the "public forum doctrine." This idea divides public spaces into three types:

- Traditional Public Forums: These are places like parks and sidewalks. They have the strongest free speech protections. Rules here must be content-neutral, serve a major government interest, and allow other ways to communicate. But the government can still have rules. For example, a park might close at night, so protests aren't allowed then.

- Designated Forums: These are public properties the government opens for speech, like school auditoriums. The government can limit who uses them or what topics are discussed, as long as the rules are fair and consistent. Once opened, they are like traditional public forums.

- Nonpublic Forums: These are places like airport terminals or internal mail systems. The government has a lot of control here. It can limit speech as long as the rules are reasonable and don't target specific viewpoints. For example, a school might limit what can be put in student mailboxes if it doesn't fit the school's purpose.

Supreme Court Decisions

Time, place, and manner rules help keep order. For example, you can't yell "fire" in a crowded theater if there's no fire. This would cause panic and harm. Justice Holmes said in 1918, "Even the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing panic." While free speech is important, public order and peace are also important. These rules balance those values.

Judges decide if a speech limit is fair by checking the four requirements: content-neutral, narrowly tailored, significant government interest, and ample alternatives. If these are met, the limit is usually allowed.

Prior Restraint

Prior restraint means the government tries to stop speech before it happens. This is very hard for the government to do. It must show that punishing the speech afterwards isn't enough. It also must prove that allowing the speech would cause "direct, immediate, and irreparable damage" to the country.

Since 1931, U.S. courts have rarely allowed prior restraint. However, in 1988, the Supreme Court allowed a school principal to remove content from a student newspaper. The Court said the school was not violating students' rights because the paper was sponsored by the school.

Speech Not Protected

Falsehoods

Laws against commercial fraud (lying in business), counterfeit currency (fake money), and perjury (lying under oath) are allowed. But some other false statements can be protected.

Inciting Immediate Violence

Speech that encourages immediate illegal actions or violence is not protected. This rule replaced an older, weaker test.

Fighting Words

These are words that are so offensive they might cause someone to immediately fight back or break the peace. Such words are not protected free speech.

True Threats

Threats that are serious and meant to cause fear of harm are not protected.

Obscenity

Obscenity is speech that is very offensive and has no serious artistic, political, or scientific value. What counts as obscene is decided by "community standards." This type of speech is not legally protected.

Defamation

Defamation means making false statements that harm someone's reputation. This includes libel (written lies) and slander (spoken lies). People can be sued for defamation. However, it's harder for public figures to win defamation cases. They must prove the false statement was made with "actual malice" (meaning the person knew it was false or didn't care if it was).

Government Speech

When the government itself is speaking, it can control its own message. This means the government can censor what it says.

Public Employee Speech

If you work for the government, what you say as part of your job duties is not protected by the First Amendment. Your employer can discipline you for it. However, if you speak publicly about matters of public interest, outside of your job duties, you usually have First Amendment protection. This does not apply to private companies.

Student Speech

In 1969, the Supreme Court said that students in public schools have broad First Amendment protection. Schools cannot censor students unless their speech causes "substantial interference with school discipline or the rights of others."

Later rulings have clarified this. In 1988, the Court allowed censorship in school newspapers if they were not set up as open forums for student expression. But courts have also struck down school rules that were too vague or stopped criticism of the school.

These protections also apply to public colleges and universities. Student newspapers at colleges, if set up as open forums, have strong protection.

National Security

Some speech related to national security is not protected.

- Military Secrets: Sharing military secrets or information about national defense is not protected. This is true even if no harm is intended.

- Inventions: The government can stop inventors from publishing or sharing information about inventions that might harm U.S. national security. This is done through "secrecy orders."

- Nuclear Information: Information about atomic weapons or nuclear materials is automatically classified (secret). The government has tried, but usually failed, to stop the publication of nuclear bomb designs.

- Weapons: It's a crime to teach or show how to make or use explosives or weapons of mass destruction if you intend or know the information will be used for a crime.

Censorship

While personal free speech is usually respected, mass publishing and the press have some limits. Recent issues include:

- The U.S. military censoring blogs written by soldiers.

- The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) censoring TV and radio for obscenity. (The FCC only regulates over-the-air broadcasts, not cable or satellite.)

- Scientology trying to stop criticism, claiming religious freedom.

- The Library of Congress blocking access to WikiLeaks.

The U.S. ranking in worldwide Press Freedom Index has changed over the years. It was 17th in 2002, fell to 53rd in 2006 (due to arrests of journalists and bad relations with the government), and then improved to 20th in 2010. In 2020, it was 45th.

Internet Speech

The Supreme Court has given full First Amendment protection to the Internet. In 1997, the Court struck down parts of a law trying to regulate Internet content. In 2002, it ruled again that limits on Internet content are usually unconstitutional.

However, in 2003, the Supreme Court said Congress could require public schools and libraries to install filters on their computers if they get federal funding. The Court said this was okay because adults could ask librarians to turn off the filters or unblock sites.

Private Companies and Speech

Many people think the First Amendment stops anyone from limiting free speech. But the First Amendment mainly stops the U.S. Congress and state/local governments from doing so. It generally does not apply to private people or businesses.

For example, private social media sites like Facebook and Twitter are not bound by the First Amendment. They create their own rules about what users can say. They try to balance free expression with removing harmful speech.

Some people worry that free speech is being harmed because so many people use the Internet and social media.

College Campuses

The First Amendment protects speech at public colleges and universities. This limits how much school leaders can create strict "speech codes." However, there are still debates about free speech on campuses. These include questions about school policies, academic freedom, and the general atmosphere for different opinions.

In 2014, the University of Chicago created the "Chicago Statement." This policy aims to fight censorship on campus. Many other top universities have adopted it. Groups like the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) rank colleges on free speech. They also list the "worst colleges for free speech."

There's a lot of discussion about whether American campuses are open or hostile to certain views, especially conservative ones. Some critics say student activists try to shut down speakers they disagree with. Others argue that incidents of speech being suppressed are rare and not always aimed at one political side.

Further reading

- Cronin, Mary M. (ed.) An Indispensable Liberty: The Fight for Free Speech in Nineteenth-Century America. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2016.

- Eldridge, Larry. A Distant Heritage: The Growth of Free Speech in Early America. New York: New York University Press, 1995.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |