John Marshall Harlan II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

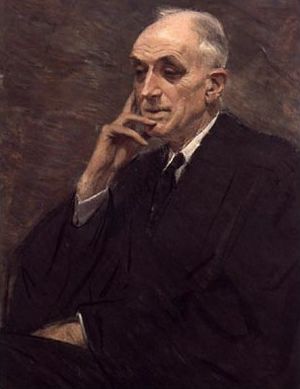

John Marshall Harlan II

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office March 28, 1955 – September 23, 1971 |

|

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Robert H. Jackson |

| Succeeded by | William Rehnquist |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit | |

| In office February 10, 1954 – March 27, 1955 |

|

| Nominated by | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Augustus Noble Hand |

| Succeeded by | J. Edward Lumbard |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Marshall Harlan

May 20, 1899 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 29, 1971 (aged 72) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Emmanuel Church Cemetery, Weston, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Spouse |

Ethel Andrews

(m. 1928) |

| Children | 1 |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | John Marshall Harlan (grandfather) |

| Education | Princeton University (AB) Balliol College, Oxford New York Law School (LLB) |

John Marshall Harlan (born May 20, 1899 – died December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and judge. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. People usually call him John Marshall Harlan II to tell him apart from his grandfather, John Marshall Harlan. His grandfather also served on the U.S. Supreme Court many years earlier.

Harlan studied at schools in Canada and then at Princeton University in the U.S. He won a special scholarship called a Rhodes Scholarship. This allowed him to study law at Balliol College, Oxford in England. After returning to the U.S., he worked at a law firm and continued his law studies.

Later, he worked for the government as a lawyer. In 1954, he became a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Just one year later, President Dwight Eisenhower chose him to join the Supreme Court of the United States.

Justice Harlan was known for being a more traditional judge. He believed courts should not try to change society too much. He often stuck to past legal decisions. He also thought that states should have more power than the federal government in some areas. However, he also believed the Constitution protected many important rights for people. He retired from the Supreme Court because he was very sick. He passed away three months later.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Marshall Harlan was born on May 20, 1899, in Chicago, Illinois. His father, John Maynard Harlan, was a lawyer and politician. John had three sisters. His family had a long history of being involved in politics and law. His grandfather, also named John Marshall Harlan, was a Supreme Court justice from 1877 to 1911.

As a young person, Harlan went to schools in Chicago and then to boarding schools in Canada. After finishing school, he went to Princeton University in 1916. At Princeton, he was a leader and helped edit the school newspaper. He graduated in 1920.

After Princeton, he received a Rhodes Scholarship. This allowed him to study law at Balliol College, Oxford in England for three years. He was the first Rhodes Scholar to become a Supreme Court justice.

Becoming a Lawyer

When he came back to the U.S. in 1923, Harlan started working at a major law firm. He also studied law at New York Law School and became a lawyer in 1925.

From 1925 to 1927, Harlan worked as a government lawyer. He helped lead the team that enforced Prohibition laws in New York. He also investigated problems with city projects and prosecuted officials involved in wrongdoing. In 1930, he returned to his law firm and became a partner. He became a top trial lawyer there.

As a trial lawyer, Harlan worked on several important cases. He helped settle a large inheritance case involving a woman who left her money to charities. He also worked on cases about how companies could pay out their profits. During this time, he even represented famous boxer Gene Tunney in a legal dispute.

Serving in World War II

During World War II, Harlan joined the military. He served as a colonel in the United States Army Air Force from 1943 to 1945. He worked in England, helping to analyze military operations. For his service, he received awards from the United States, France, and Belgium.

After the war, Harlan went back to his private law practice. In 1951, he returned to public service. He led the New York State Crime Commission. Here, he investigated the connections between organized crime and the state government. He also looked into illegal gambling activities.

Personal Life

In 1928, John Harlan married Ethel Andrews. Ethel had been married before. They met at a Christmas party and got married on November 10, 1928.

Harlan was a Presbyterian. He had an apartment in New York City and a summer home in Connecticut. He enjoyed playing golf. He also wore a gold watch that belonged to his grandfather, the first Justice Harlan. When he joined the Supreme Court, he even used the same furniture that his grandfather had in his office.

John and Ethel Harlan had one daughter, Evangeline Dillingham. She was born in 1932 and later had five children. One of her daughters, Kate Dillingham, is a professional cellist.

Becoming a Judge

President Dwight D. Eisenhower chose Harlan to be a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1954. Harlan knew this court well because he had often argued cases there. The United States Senate approved his appointment, and he started his work as a judge on February 10, 1954. He served on this court for about a year.

Joining the Supreme Court

On January 10, 1955, President Eisenhower nominated Harlan to become an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was chosen to replace Justice Robert H. Jackson, who had passed away. When he was nominated, Harlan simply told reporters, "I am very deeply honored."

His nomination came soon after the Supreme Court made a very important decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education. This decision said that separating students by race in public schools was against the Constitution. Some senators from the southern states tried to delay Harlan's approval. They believed he would support ending segregation and protecting civil rights.

Harlan was one of the first Supreme Court nominees to appear before the Senate Judiciary Committee to answer questions. Today, all Supreme Court nominees are questioned by this committee. The Senate finally approved him on March 16, 1955, by a vote of 71 to 11. He officially started his work on the Supreme Court on March 28, 1955.

On the Supreme Court, Harlan often voted similarly to Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was a mentor to him. Harlan was a close friend of Justice Hugo Black, even though they often disagreed on legal issues.

Justice Harlan was very close to the young lawyers who worked for him, called law clerks. He continued to advise them even after they left his office. He would hold yearly get-togethers and display pictures of their children.

People who worked with Justice Harlan remembered him for being kind and respectful. He treated other justices, clerks, and lawyers with great consideration. Even when he strongly disagreed with legal ideas, he never criticized anyone personally. Harlan was considered one of the most thoughtful leaders on the Warren Court.

Harlan's Legal Ideas

Harlan's legal approach is often called conservative. He believed that past legal decisions, called precedent, were very important. He thought courts should usually stick to what had been decided before.

He also believed that most problems should be solved by the political process, like through laws passed by Congress. He thought courts should only play a small role in making big changes.

Even though he was conservative, Harlan did not support the Vietnam War. He tried, along with other justices, to get the Court to hear cases challenging the war's legality.

Equal Protection Clause

The Supreme Court made several important decisions about equal rights early in Harlan's time on the Court. In these cases, Harlan usually voted to support civil rights. This was similar to his grandfather, who was the only justice to disagree in the famous Plessy v. Ferguson case, which allowed segregation.

Harlan voted with the majority in Cooper v. Aaron. This case forced officials in Arkansas to desegregate public schools. He also joined the decision in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, which said states could not change voting district lines to reduce the voting power of African-Americans. He also agreed with the unanimous decision in Loving v. Virginia, which ended state laws that banned marriage between people of different races.

Due Process Clause

Justice Harlan believed the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause protected many important rights. He thought it protected rights that were not specifically written in the Constitution. This idea is called "substantive due process."

However, Harlan also believed judges should be careful not to make up new rights. He thought judges should respect history and the basic values of society. He also valued federalism, which means sharing power between federal and state governments.

Justice Black disagreed with Harlan on this point. Black thought that saying some rights were more "fundamental" than others was unfair. But the Supreme Court has generally agreed with Harlan's idea. It continues to use the idea of substantive due process in many cases.

Bill of Rights and States

Justice Harlan strongly disagreed with the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment automatically applied the entire Bill of Rights to the states. When the Bill of Rights was first created, it only limited the federal government.

Harlan believed that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause only protected "fundamental" rights. So, if a right from the Bill of Rights was truly "fundamental," then he agreed it should apply to the states. For example, he thought the First Amendment's free speech protection applied to states. But he did not think the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination applied to states.

Harlan's approach was similar to other justices like Benjamin Cardozo and Felix Frankfurter. Justice Black disagreed, saying it was unfair to pick and choose which rights applied.

Over time, the Supreme Court has adopted parts of Harlan's idea. It has decided that only some parts of the Bill of Rights apply to the states. This is called "selective incorporation." However, the Court has applied many more rights to the states than Harlan thought it should.

First Amendment Rights

Justice Harlan supported many important decisions about the separation of church and state. For example, he voted that states could not require religious tests for public office. He also joined the decision that made it unconstitutional for states to require official prayers in public schools. He also voted to strike down a law that banned teaching evolution.

Harlan generally had a broad view of First Amendment rights, like freedom of speech and the press. He believed freedom of speech was a "fundamental principle of liberty."

He agreed with the decision in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. This case made it harder for public officials to win libel lawsuits against newspapers. It required them to prove the publisher acted with "actual malice." In Street v. New York, Harlan wrote the Court's opinion. It said the government could not punish someone for insulting the American flag. He also noted that the Supreme Court had always rejected stopping publications before they were printed.

When Harlan was a lower court judge, he upheld the conviction of Communist Party USA leaders. But later, as a Supreme Court justice, he wrote opinions overturning similar convictions. He found them unconstitutional in cases like Yates v. United States.

Justice Harlan is also known for helping establish the idea that the First Amendment protects the freedom to join groups. In NAACP v. Alabama, he wrote the Court's opinion. It said Alabama could not force the NAACP to share its membership lists. However, he did not believe people could exercise their First Amendment rights anywhere they wanted. He agreed with decisions that upheld trespassing convictions for protesters on government property. He disagreed with decisions that allowed sit-ins at public libraries or students wearing armbands to protest in schools.

Voting Rights

Justice Harlan disagreed with the idea that the Constitution required "one man, one vote." This principle means that voting districts must have roughly equal populations. He believed that courts should stay out of political issues like drawing district lines.

However, the Supreme Court disagreed with Harlan in the 1960s. In Baker v. Carr, the Court said that courts could review issues about unfair voting districts. Harlan disagreed, saying the plaintiffs did not show their individual rights were violated.

Then, in Wesberry v. Sanders, the Court said that districts for the United States House of Representatives must have roughly equal populations. Harlan strongly disagreed. He argued that the Court's decision was wrong based on the Constitution's history and text. He believed only Congress should have the power to require equal populations in districts.

Harlan was the only justice to disagree in Reynolds v. Sims. In this case, the Court extended the "one man, one vote" principle to state legislative districts. He argued that the Equal Protection Clause was not meant to cover voting rights. He thought the problem of unfair districts should be solved by the political process, not by courts.

For similar reasons, Harlan disagreed with other decisions that struck down voter qualifications. He believed the Equal Protection Clause was not intended to deal with state voting matters. He also disagreed with the Court's decision that ended the use of the poll tax for voting.

Retirement and Death

John M. Harlan's health began to get worse as he got older. His eyesight started to fail in the late 1960s. He had to hold papers very close to his eyes. His clerks and his wife would read to him. He was very sick when he retired from the Supreme Court on September 23, 1971.

Harlan died from spinal cancer three months later, on December 29, 1971. He was buried in Connecticut. President Richard Nixon chose William Rehnquist to replace him on the Supreme Court. Rehnquist later became the Chief Justice.

Even though he often disagreed with the majority, Harlan is seen as one of the most important Supreme Court justices of the 20th century. His many professional and Supreme Court papers are kept at Princeton University. His wife, Ethel Harlan, passed away a few months after him.

See also

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 9)

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Warren Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Burger Court

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |