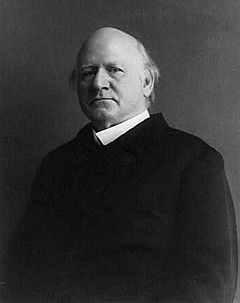

John Marshall Harlan facts for kids

John Marshall Harlan (born June 1, 1833 – died October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician. He served as a judge on the United States Supreme Court. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" because he disagreed with the majority in many important cases. These cases often limited people's rights, especially in cases like the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson. Many of Harlan's ideas, which he wrote about in his dissenting opinions, later became the official view of the Supreme Court, especially from the 1950s onward. His grandson, John Marshall Harlan II, also became a Supreme Court judge.

Harlan was born into a well-known family in Kentucky. When the American Civil War began, he strongly supported the Union side. He even helped create the 10th Kentucky Infantry military group. Even though he didn't agree with the Emancipation Proclamation, he fought in the war until 1863. After the war, he became the Attorney General of Kentucky. Later, he joined the Republican Party and quickly became a leader in Kentucky. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes chose him to be a judge on the Supreme Court.

Harlan's legal ideas were shaped by his belief in a strong national government. He also cared about people who were struggling financially. He believed that the Reconstruction Amendments (changes to the Constitution after the Civil War) completely changed how the federal government and state governments worked together. He famously disagreed with the decisions in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). These decisions allowed states and private groups to have segregation, which meant keeping people of different races separate. He also wrote dissenting opinions in other big cases, like Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895), which stopped a federal income tax. He was the first Supreme Court judge to say that the Bill of Rights should apply to the states. His opinion in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago (1897) made sure that the government had to pay fairly for private property it took.

Quick facts for kids

John Marshall Harlan

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office November 29, 1877 – October 14, 1911 |

|

| Nominated by | Rutherford Hayes |

| Preceded by | David Davis |

| Succeeded by | Mahlon Pitney |

| Attorney General of Kentucky | |

| In office September 1, 1863 – September 3, 1867 |

|

| Governor | Thomas Bramlette |

| Preceded by | Andrew James |

| Succeeded by | John Rodman |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 1, 1833 Boyle County, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 1911 (aged 78) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Know Nothing (1854–1858) Opposition (1858–1860) Constitutional Union (1860) Unionist (1861–1867) Republican (1868–1911) |

| Spouse |

Malvina Shanklin

(m. 1856) |

| Relations | John Marshall Harlan (grandson) |

| Children | 6 (including James and John Maynard) |

| Education | Centre College (BA) Transylvania University |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1863 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 10th Kentucky Infantry |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Marshall Harlan was born in 1833 in Kentucky. His family was well-known and had lived in the area since 1779. His father, James Harlan, was a lawyer and a famous politician. John's mother was Elizabeth Davenport. John grew up on his family's land near Frankfort, Kentucky. He was named after Chief Justice of the United States John Marshall, whom his father admired greatly.

John had several older brothers. One of his half-brothers, Robert James Harlan, was born into slavery in 1816. Their father raised Robert in his home and had him taught by John's older brothers. Historians believe Robert became very successful, earning a lot of money in the California Gold Rush. He stayed close to the Harlan family. Some think this connection might have influenced John Marshall Harlan's strong belief in equal rights for all people.

After going to school in Frankfort, John went to Centre College. He was a good student and graduated with honors. While his mother wanted him to be a merchant, his father wanted him to become a lawyer. So, John joined his father's law practice in 1852. His father also sent him to law school at Transylvania University in 1850. John finished his law studies in his father's office and became a lawyer in Kentucky in 1853.

Political Career and Public Service

Early Political Steps (1851–1863)

Like his father, Harlan was a member of the Whig Party. In 1851, he got an early start in politics when he was offered a job as a state official. He held this job for eight years, which helped him become known across Kentucky. When the Whig Party broke apart, Harlan joined the Know Nothings. Even though he didn't fully agree with their views against Catholics, he was popular enough to be elected as a judge in Franklin County, Kentucky, in 1858.

In the 1850s, Harlan spoke out against both those who wanted to end slavery completely and those who strongly supported it. He was like many Southerners who didn't want their states to leave the Union. He supported the Constitutional Union Party in the 1860 presidential election. Harlan even gave speeches for the party throughout Kentucky. After Abraham Lincoln won the election, Harlan worked to keep Kentucky from leaving the United States. He wrote articles supporting the Union and joined a local militia group.

When the state decided to remove all Confederate forces, Harlan helped create a military company. This group became the 10th Kentucky Infantry. Harlan served in the American Civil War until his father died in February 1863. At that time, he left the army and went back home to support his family.

Leading the Republican Party (1863–1877)

Soon after leaving the army, Harlan was chosen by the Union Party to run for Attorney General of Kentucky. He promised to strongly support the war effort and won the election easily. As attorney general, he gave legal advice and represented the state in court.

After the Civil War ended in 1865, Harlan didn't immediately join the Democratic or Republican parties. He felt the Democrats were too accepting of former rebels, and he disagreed with some of the Republicans' plans for Reconstruction. He tried to get re-elected in 1867 with a different party, but he lost. After this defeat, Harlan joined the Republican Party and supported Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868.

Harlan moved to Louisville and started a successful law firm. While working as a lawyer, he also helped build up the Republican Party in Kentucky. He ran for governor of Kentucky in 1871 and again in 1875, but he lost both times to Democrats. However, these campaigns made him the leader of the Republican Party in Kentucky. In 1876, he helped Rutherford B. Hayes become the Republican candidate for president and campaigned for him.

Supreme Court Justice

Becoming a Justice

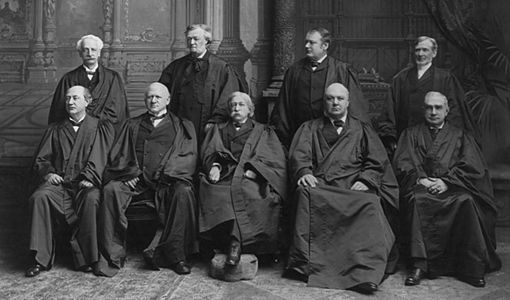

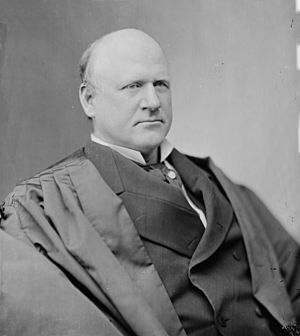

President Hayes considered Harlan for several important jobs. Finally, Hayes decided to appoint Harlan to the Supreme Court. This was after Justice David Davis resigned in 1877. Hayes wanted to choose a Southerner for the Supreme Court after a very close and disputed presidential election. Even though some Republicans had concerns, the Senate unanimously approved Harlan's appointment on November 29, 1877.

Life on the Court

Harlan truly enjoyed his time as a Supreme Court Justice, serving until he died in 1911. He got along well with the other judges. Even when he strongly disagreed with them on legal matters, he kept good personal relationships. He often faced money problems, especially as he sent his three sons to college. He even thought about leaving the Court to go back to being a private lawyer. But he decided to stay and earned extra money by teaching law at Columbian Law School, which is now George Washington University Law School.

When Harlan started, the Supreme Court had a lot of cases, but few involved big constitutional questions. Judges also traveled to different parts of the country to hear cases in lower federal courts. Harlan traveled to Chicago for his circuit until 1896. After another judge died, he switched to his home circuit in Kentucky. Harlan became the most senior associate justice in 1897. He even served as the acting Chief Justice after Melville Fuller died in 1910.

Harlan's Legal Ideas

During Harlan's time on the Supreme Court, many major cases dealt with new industries and the Reconstruction Amendments. In the 1880s, the Supreme Court often favored a "hands-off" approach to business (called laissez-faire). They would strike down laws that regulated businesses. At the same time, they allowed states to limit the rights of African Americans. Harlan often disagreed with his fellow judges. He usually voted to support federal rules and to protect the civil rights of African Americans.

His legal opinions were shaped by his belief in a strong national government. He also felt sympathy for people who were not well-off. He believed the Reconstruction Amendments had completely changed the relationship between the federal government and the states. Even though Harlan thought the Court could review many state and federal actions, he generally preferred that lawmakers (legislatures) make the laws, rather than judges.

Important Early Cases (1877–1896)

In 1875, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. This law made it illegal to separate people by race in public places like trains. The Supreme Court didn't rule on this law until 1883, when it struck it down in the Civil Rights Cases. The majority of judges said that the Thirteenth Amendment only ended slavery. They also said the Fourteenth Amendment didn't allow Congress to stop private businesses from separating people by race.

Harlan was the only judge who disagreed strongly. He said the majority had twisted the meaning of the Reconstruction Amendments. He argued that the Fourteenth Amendment gave Congress the power to regulate public places. He also believed the Thirteenth Amendment allowed Congress to remove all signs of slavery, like limits on people's freedom to move around.

Harlan was the first judge to argue that the Fourteenth Amendment meant the Bill of Rights should also apply to the states. He made this argument in the case of Hurtado v. California (1884).

In 1895, Harlan was one of four judges who disagreed with the decision in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. This case struck down a federal income tax. Harlan called the majority's decision a "disaster" because it weakened the national government's powers. He was the only judge to disagree in another 1895 case, United States v. E. C. Knight Co. In this case, the Court greatly limited the federal government's power to stop monopolies under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Harlan wrote that only the national government could properly deal with issues that hurt the country's entire economy.

Plessy v. Ferguson

In 1896, the Supreme Court made a very important decision in Plessy v. Ferguson. This case created the idea of "separate but equal." While the Civil Rights Cases had stopped a federal law against segregation by private businesses, the Plessy decision allowed state governments to have segregation. The Court said that a law that simply made a legal difference between white and Black people did not destroy their legal equality. They also said the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to ensure "absolute equality" but not to stop differences based on race or force people to mix if they didn't want to.

Harlan was the only judge who strongly disagreed. He wrote that the decision would be "quite as harmful as the decision made by this tribunal in the Dred Scott Case." He believed that the Thirteenth Amendment should stop segregation in public places because it created "badges of slavery" for African Americans. He also argued that segregation in public places violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

Harlan famously wrote that "our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens." He rejected the idea that the law was fair to all races. He wrote that "everyone knows that the statute in question [was intended] to exclude colored people from coaches occupied by or assigned to white persons." He added that the law was "cleverly designed" to undo the results of the Civil War.

Later Important Cases (1897–1911)

Harlan wrote the main opinion in Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Co. v. City of Chicago (1897). This decision said that if the state took private property, it had to pay fair compensation. This was the first time a part of the Bill of Rights (the Fifth Amendment's Takings Clause) was applied to state governments.

Harlan also wrote the main opinion in Northern Securities Co. v. United States. This was the first time the Court used the Sherman Antitrust Act to break up a large company.

In his final years on the Court, Harlan continued to write dissenting opinions in major cases. He disagreed in Lochner v. New York (1905), a case about workers' hours. He was the only judge to disagree in Ex parte Young (1908), arguing that the Eleventh Amendment stopped lawsuits against state officials acting for the state. In 1911, he partly disagreed with the decision in Standard Oil Company of New Jersey v. United States. He argued against the Court's new "rule of reason," which said that some monopolies might be allowed. Harlan felt that this rule was not in the original law and that the Court was taking over Congress's job of making laws.

Death and Legacy

Harlan died on October 14, 1911, after serving on the Supreme Court for 33 years. This was one of the longest terms on the Court at that time. He was the last judge from the earlier Waite Court to still be serving. He is buried in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Harlan often had money problems during his time as a judge. He left very little money for his wife, Malvina Shanklin Harlan, and his two unmarried daughters. After his death, important lawyers helped set up a fund to support his family.

Harlan was largely forgotten for many years after his death. However, his reputation began to grow in the mid-1900s. Today, many experts consider him one of the greatest Supreme Court judges of his time. He is best known as "The Great Dissenter," especially for his strong disagreement in Plessy v. Ferguson. Many scholars believe that Harlan understood the Reconstruction Amendments better than other judges of his time. He believed they created a national right against racial discrimination. His idea that the Fourteenth Amendment made the Bill of Rights apply to the states has also been largely accepted by the Supreme Court today.

John Marshall Harlan is honored by several schools, including John Marshall Harlan Community Academy High School in Chicago and John Marshall Harlan High School in Texas. During World War II, a ship called the SS John M. Harlan was named after him. His college, Centre College, created the John Marshall Harlan Professorship in Government in his honor.

On March 12, 1906, Harlan gave a King James Version Bible to the Supreme Court. This Bible is now known as the "Harlan Bible." Since 2015, every new Supreme Court judge has signed this Bible after taking their oath of office.

Personal Life

Family

In December 1856, Harlan married Malvina French Shanklin. She was the daughter of a businessman from Indiana. Friends and Malvina's own writings say they had a happy marriage that lasted until Harlan's death. They had six children: three sons and three daughters. Their oldest son, Richard, became a minister and president of Lake Forest College. Their second son, James S. Harlan, became a lawyer and later chairman of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Their youngest son, John Maynard Harlan, also became a lawyer. John Maynard's son, John Marshall Harlan II, served as a Supreme Court Justice from 1955 to 1971.

Religious Beliefs

Harlan was a deeply religious Christian. His Christian beliefs were very important in his life and in his work as a Supreme Court judge. He was an elder at the New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. From 1896 until his death in 1911, he taught a Sunday school class there for adult men.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |