Loving v. Virginia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Loving v. Virginia |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued April 10, 1967 Decided June 12, 1967 |

|

| Full case name | Richard Perry Loving, Mildred Jeter Loving v. Virginia |

| Citations | 388 U.S. 1 (more)

87 S. Ct. 1817; 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010; 1967 U.S. LEXIS 1082

|

| Prior history | Defendants convicted, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 6, 1959); motion to vacate judgment denied, Caroline County Circuit Court (January 22, 1959); affirmed in part, reversed and remanded, 147 S.E.2d 78 (Va. 1966); cert. granted, 385 U.S. 986 (1966). |

| Argument | Oral argument |

| Holding | |

| Bans on interracial marriage violate the Equal Protection Clause and Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by unanimous |

| Concurrence | Stewart |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. XIV; Va. Code §§ 20–58, 20–59 | |

|

This case overturned a previous ruling or rulings

|

|

| Pace v. Alabama (1883) | |

Loving v. Virginia was a very important civil rights case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1967. The Court ruled that laws banning marriage between people of different races were against the United States Constitution. These laws were called "anti-miscegenation laws."

The case was about Mildred Loving, who was a woman of color, and her white husband, Richard Loving. In 1958, they were sentenced to a year in prison just for getting married. Their marriage broke Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This law made it a crime for white people and "colored" people to marry each other.

The Lovings fought their conviction all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In June 1967, the Supreme Court made a unanimous decision. They sided with the Lovings and said Virginia's law was unconstitutional. This decision ended all race-based restrictions on marriage in the United States.

Contents

Understanding Anti-Miscegenation Laws

What were these laws?

Anti-miscegenation laws were rules that made it illegal for people of different races to marry. Some of these laws had been around in certain states since the early days of the United States.

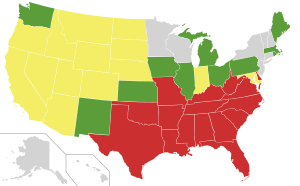

After the American Civil War, many states in the South brought back these strict laws. By 1967, 16 states, mostly in the Southern United States, still had these laws.

Who were Mildred and Richard Loving?

Mildred Delores Loving was a woman who identified as Native American and also had African American and Portuguese ancestry. Richard Perry Loving was a white man.

Both of their families lived in Caroline County, Virginia. This area had very strict Jim Crow laws, which enforced racial segregation. However, their town, Central Point, had a history of being a mixed-race community. Mildred and Richard met in high school and fell in love.

Mildred became pregnant. In June 1958, they traveled to Washington, D.C. to get married. They did this to avoid Virginia's law against interracial marriage. A few weeks after they returned home, police raided their house. They were told their marriage certificate was not valid in Virginia.

Earlier Court Cases on Interracial Marriage

Before Loving v. Virginia, there were other court cases about interracial relationships. For example, in 1878, the Supreme Court of Virginia said a marriage between a black man and a white woman, legally done in Washington, D.C., was "invalid" in Virginia.

Another important case was Perez v. Sharp in 1948. In this case, the Supreme Court of California recognized that bans on interracial marriage went against the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This was a big step forward.

The Supreme Court's Decision

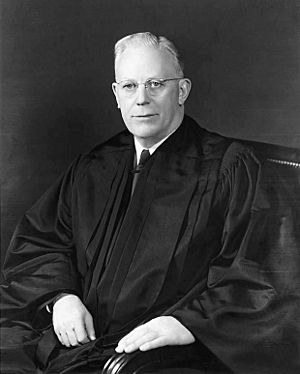

On June 12, 1967, the Supreme Court made a unanimous decision. All nine justices agreed with the Lovings. They overturned the Lovings' criminal convictions and struck down Virginia's anti-miscegenation law. Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote the Court's opinion.

Equal Protection and Due Process

The Court looked at whether Virginia's law violated the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment has two important parts:

- The Equal Protection Clause says that no state can "deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." This means everyone should be treated equally under the law.

- The Due Process Clause says that states cannot take away a person's "life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." This means people have basic rights that the government cannot unfairly remove.

Virginia argued that its law treated everyone equally because the punishment was the same for both white and non-white people who broke the law. For example, a white person marrying a black person faced the same penalty as a black person marrying a white person.

However, the Supreme Court rejected this idea. They said that any law based only on race is suspicious. The Court found that Virginia's law had no real purpose other than to keep "White Supremacy." They said that restricting the freedom to marry based on race clearly violates the Equal Protection Clause.

The Court also said that the freedom to marry is a very important constitutional right. Taking away this basic freedom just because of someone's race was unconstitutional. It violated the Due Process Clause.

Impact of the Decision

Interracial Marriage in the U.S.

Even after the Supreme Court's decision, some states still had anti-miscegenation laws on their books. However, the Loving decision made these laws impossible to enforce.

Alabama was the last state to officially remove its anti-miscegenation language from its state constitution. This happened in 2000, when 60% of voters approved a change.

After Loving v. Virginia, the number of interracial marriages grew across the United States. In 1960, only 0.4% of marriages were interracial. By 2015, almost 50 years after the Loving decision, this number had grown to 16%.

Loving v. Virginia in Popular Culture

The date of the decision, June 12, is now known as Loving Day. It is an unofficial annual celebration of interracial marriages in the United States.

Mildred Loving was honored in 2014 as one of the "Virginia Women in History." In 2017, a historical marker was placed in Richmond, Virginia, to tell the Lovings' story.

The story of Mildred and Richard Loving has also been told in several films:

- Mr. and Mrs. Loving (1996) was an early film about their story.

- The Loving Story (2012) was a documentary that won an award.

- Loving (2016) was a movie based on the documentary. The actress who played Mildred, Ruth Negga, was nominated for an Academy Award.

- The Loving Generation (2018) was a four-part film that looked at the lives of biracial children born after the Loving decision.

Their story has also inspired music and books. Nanci Griffith's 2009 album The Loving Kind includes a song about them. A 2015 novel by Gilles Biassette, L'amour des Loving, also tells their story.

See also

In Spanish: Caso Loving contra Virginia para niños

In Spanish: Caso Loving contra Virginia para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |