Racial Integrity Act of 1924 facts for kids

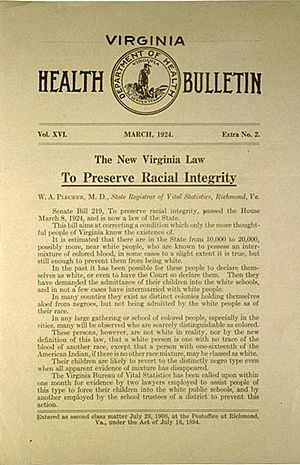

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly passed a law called the Racial Integrity Act. This law made racial segregation stronger by stopping people of different races from marrying each other. It also said that a "white" person was someone who had "no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian." This act was supported by ideas like eugenics and scientific racism, especially by Walter Plecker. He was a white supremacist who worked as the registrar for Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics.

The Racial Integrity Act made it a rule that all birth certificates and marriage certificates in Virginia had to state a person's race as either "white" or "colored." The law said that all non-whites, including Native Americans, were "colored." This act was one of several "racial integrity laws" in Virginia. These laws aimed to keep racial hierarchies in place and stop different races from mixing. Other laws included the Public Assemblages Act of 1926, which required separate public meeting areas for different races. A 1930 law even said that anyone with any African family background was considered black. This was known as the "one-drop rule."

In 1967, the Racial Integrity Act was officially ended by the Supreme Court of the United States in their decision called Loving v. Virginia. Later, in 2001, the Virginia General Assembly said they were sorry for the Racial Integrity Act. They stated it was used as a "scientific" way to hide racist beliefs.

Contents

How the Racial Integrity Act Came to Be

In the 1920s, Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker, Virginia's registrar of statistics, worked with a group called the Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America. They convinced the Virginia General Assembly to pass the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. The Anglo-Saxon Club was started in Richmond in 1922 by John Powell. Within a year, this club for white men had over 400 members across Virginia.

In 1923, the Anglo-Saxon Club opened two branches in Charlottesville. One was for the town, and another was for students at the University of Virginia. A main goal of the club was to stop "amalgamation," which meant preventing marriages between different races. Members also claimed to support ideas of fair play.

Laws against interracial marriage (called Anti-miscegenation laws) had existed long before the idea of eugenics became popular. These laws, which banned marriage between whites and non-whites, first appeared during the Colonial era. At that time, slavery had become a system based on race. Such laws were in effect in Virginia and many other parts of the United States until the 1960s.

The first law banning all marriage between whites and Black people was passed in the colony of Virginia in 1691. Other colonies like Maryland followed this example. By 1913, 30 out of the 48 states at the time, including all Southern states, had these laws.

The "Pocahontas Exception" Explained

The Racial Integrity Act had a special rule called the Pocahontas Clause or Pocahontas Exception. This rule allowed people who had a small amount of American Indian ancestry (less than 1/16) to still be considered white. This was unusual because the law otherwise followed a strict "one-drop rule" for other non-white ancestries.

This exception was added to the law because some important families in Virginia, known as the First Families of Virginia, were worried. Many of them proudly claimed to be descendants of Pocahontas. They feared the new law would affect their social standing. The exception stated:

It shall thereafter be unlawful for any white person in this State to marry any save a white person, or a person with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian. For the purpose of this act, the term "white person" shall apply only to the person who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons".

While definitions of "Indian" and "colored" had changed over time, this was the first time that "whiteness" itself was officially defined by law.

How the Law Was Enforced

Once these laws were passed, Walter Plecker was in charge of making sure they were followed. A year after signing the act, Governor E. Lee Trinkle asked Plecker to be less strict with Indians. He asked Plecker not to "embarrass them any more than possible." Plecker replied that he did not see how it was unfair to stop them from marrying white people. He also said it was not humiliating to prevent them from being recognized as Indians, attending white schools, or riding in white coaches.

Some people who supported eugenics were not happy with the "Pocahontas Exception." They tried to add another change to the Racial Integrity Act in 1926. This change would have made the "one-drop rule" even stricter for American Indian ancestry. If it had passed, thousands of people considered "white" would have been reclassified as "colored." However, this amendment did not pass.

Plecker was very concerned about the "Pocahontas Clause." He worried that the white race would be "swallowed up by the quagmire of mongrelization." This concern grew after marriage cases like those of the Johns and Sorrels families. In these cases, the women argued that family members listed as "colored" were actually Native American. This was because historical records of race were often unclear.

Effects of the Racial Integrity Act

The Racial Integrity Act had a big negative impact on Virginia's American Indian tribes. The law said that only two racial categories could be written on birth certificates: "white" and "colored." The "colored" category now included Indians and all people who appeared to be of mixed race. The effects were seen quickly. In 1930, the US Census counted 779 Indians in Virginia. By 1940, that number had dropped to 198. This meant that Indians were almost erased from official records as a group.

Walter Plecker also admitted that he enforced the Racial Integrity Act far beyond his official duties. For example, he pressured school superintendents to keep mixed-race children out of white schools. He even ordered the exhumation of dead people with "questionable ancestry" from white cemeteries. They were then reburied elsewhere.

Indians Reclassified as "Colored"

As registrar, Plecker ordered that almost all Virginia Indians be reclassified as colored on their birth and marriage certificates. He believed that most Indians had African heritage and were trying to "pass" as Indian to avoid racial segregation. Because of this, two or three generations of Virginia Indians had their ethnic identity changed on these public documents. This made it very hard for descendants of some Virginia tribes to get federal recognition later on. They could no longer easily prove their American Indian ancestry with official records.

How People Reacted to the Law

In the early 1900s, minority groups in the southern United States were often afraid to speak out because of harsh treatment. However, magazines like the Richmond Planet gave the Black community a way to share their concerns. The Richmond Planet made a difference by openly publishing the opinions of minorities. After the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 was passed, the Richmond Planet published an article about it. The article explained the act and then shared statements from its creators, John Powell and Earnest S. Cox.

Mr. Powell believed the Racial Integrity Act was needed to "preserve its superior blood" for the white race. Cox believed in what he called "the great man concept." He thought that if races mixed, it would lower the number of great white men in the world. He even claimed that non-whites would agree with his ideas:

The sane and educated Negro does not want social equality ... They do not want intermarriage or social mingling any more than does the average American white man wants it. They have race pride as well as we. They want racial purity as much as we want it. There are both sides to the question and to form an unbiased opinion either way requires a thorough study of the matter on both sides.

The Law Ends and Apologies Are Made

In 1967, the US Supreme Court made a ruling in the case Loving v. Virginia. The Court decided that the part of the Racial Integrity Act that made marriages between "whites" and "nonwhites" illegal went against the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment guarantees equal protection for all citizens.

In 1975, Virginia's General Assembly officially ended the rest of the Racial Integrity Act. In 2001, the legislature passed a bill (HJ607ER) to say they deeply regretted their part in the eugenics movement. On May 2, 2002, Governor Mark R. Warner also said he felt "profound regret for the commonwealth's role in the eugenics movement."

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |