Native American tribes in Virginia facts for kids

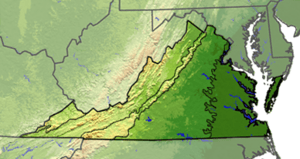

The Native American tribes in Virginia are the original peoples who live or have lived in what is now the Commonwealth of Virginia in the USA. These groups are also called Virginia Indians.

Native Americans have lived in this region for at least 12,000 years. Before Europeans arrived, about 50,000 Native people lived here. They spoke languages from three main families:

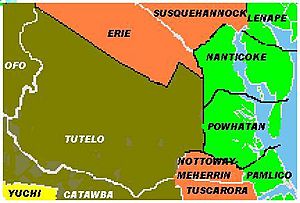

- Algonquian along the coast and Tidewater areas.

- Siouan in the Piedmont region (above the Fall Line).

- Iroquoian in the mountains and interior.

About 30 Algonquian tribes were part of the powerful Powhatan chiefdom along the coast. This group had about 15,000 people when the English first arrived.

Early European visitors wrote down some observations about Native life. They noted that Virginia Natives ate corn, meat, fish, and gathered fruits. They also believed in an afterlife.

Over time, many tribes lost their lands. Diseases brought by Europeans also caused many deaths. Some Native Americans married Europeans and African Americans. Many colonists thought Native cultures were disappearing. However, mixed-race people could still be raised with their Native American culture.

Many Native Americans kept their cultures alive. In the late 20th century, they worked hard to get official recognition from the state and federal governments. As of January 29, 2018, Virginia has seven federally recognized tribes: the Pamunkey Indian Tribe, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond, and Monacan. Six of these tribes gained federal recognition in the 21st century.

Virginia also recognizes these seven tribes and four others. Only the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes still have reservation lands. These lands were given to them by treaties with English colonists in the 1600s.

It took 19 years for federal recognition laws to pass for six of Virginia's tribes. These tribes faced challenges because they lacked reservations. Also, unfair state actions changed records of their Native American identity. Some records were even lost during the American Civil War.

State officials changed birth and marriage records under the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. They removed "Indian" identity and reclassified people as "white" or "non-white" (meaning "colored"). This was based on the "one-drop rule" which said that anyone with any African ancestry was considered black. Many Virginia Native Americans have mixed ancestry, including European or African roots. This law caused Native individuals and families to lose proof of their identity.

Since the late 1900s, many tribes who kept their culture reorganized. They pushed for federal recognition. In 2015, the Pamunkey tribe was officially recognized by the federal government.

On January 29, 2018, President Donald Trump signed a law recognizing the six other tribes. This happened after nearly two decades of effort.

Contents

History of Virginia's Native Americans

Early European Encounters (1500s)

The first Europeans in Virginia were Spanish explorers. They arrived decades before the English settled Jamestown in 1607. By 1525, the Spanish had mapped the Atlantic coast north of Florida.

In 1542, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto met the Chisca people in what is now southwestern Virginia. In 1567, another Spanish group destroyed a Chisca village called Maniatique. This site later became Saltville, Virginia.

Around 1559–60, the Spanish explored the Chesapeake Bay. They captured a Native man, possibly from the Paspahegh or Kiskiack tribe. They named him Don Luis after he was baptized. He went to Spain and received a Jesuit education. About ten years later, Don Luis returned with Spanish missionaries. They tried to set up a mission, but Native Americans attacked it in 1571, killing all the missionaries.

English attempts to settle the Roanoke Colony in 1585–87 failed. This island is now in North Carolina, but the English saw it as part of Virginia. The English learned about the local Croatan tribe and other coastal tribes.

There are no written records from Native Americans before Europeans arrived. But scholars use archaeology, language study, and anthropology to learn about their cultures. Historians also use Native American oral traditions (stories passed down through generations) to understand their past.

According to colonial historian William Strachey, Chief Powhatan took over the Kecoughtan area in 1597. He put his young son Pochins in charge there. Powhatan also moved some people to the Piankatank River.

In 1670, German explorer John Lederer wrote down a Monacan legend. The Monacan, who spoke a Siouan language, said they settled in Virginia about 400 years earlier. They were driven from the northwest by enemies. They found the Algonquian-speaking Tacci tribe (also called Doeg) already living there. The Monacan taught the Tacci how to plant maize (corn). Before that, the Doeg hunted, fished, and gathered food.

Another Monacan story says that centuries ago, the Monacan and Powhatan tribes fought over mountains in western Virginia. The Powhatan chased Monacan warriors to the Natural Bridge. There, the Monacan ambushed the Powhatan on the narrow bridge and defeated them. The Natural Bridge became a sacred place for the Monacan. The Powhatan then moved their settlements east, below the Fall Line.

Another story says the Doeg once lived in what is now King George County, Virginia. About 50 years before the English arrived at Jamestown (around 1557), the Doeg split into three groups. One group moved to Caroline County, one to Prince William, and one stayed in King George.

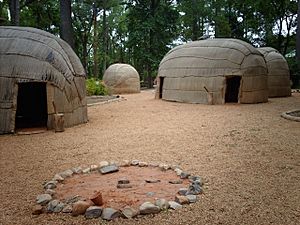

Native American Homes

The three main language groups built different types of homes. The Monacan, who spoke a Siouan language, made dome-shaped houses. These were covered with bark and reed mats.

The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy spoke Algonquian languages. They lived in houses called yihakans or yehakins. The English called them "longhouses." They were made from bent young trees tied together at the top to form a barrel shape. These frames were covered with woven mats or bark. Historian William Strachey thought bark-covered houses were for higher-status families. This is because bark was harder to get. In summer, people could roll up or remove the mat walls for air.

Inside a Powhatan house, beds were built along the long walls. They were made of posts about a foot high with small cross-poles. The bed frame was about 4 feet (1.2 m) wide and covered with reeds. Mats or skins were used for bedding and blankets. A rolled mat served as a pillow. During the day, bedding was rolled up to make space. Fires were kept burning inside for warmth in winter and to keep insects away in summer.

Wildlife was plentiful. Buffalo were common in the Virginia Piedmont until the 1700s. The Upper Potomac area was known for many wild geese. This is why its old Algonquian name was Cohongoruton (Goose River). Men and boys hunted game and caught fish and shellfish. Women gathered plants, roots, and nuts. They cooked these with meats. Women also butchered meat, prepared fish, and cooked vegetables for stew. They were largely responsible for building new houses when the group moved to find seasonal resources. Experienced women and older girls worked together, with younger children helping.

English Colonization and Conflict (1600s)

In 1607, the English started their first lasting settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. Many tribes lived in the area, speaking Algonquian, Siouan, and Iroquoian languages. Captain John Smith met many tribes, including the Wicocomico. More than 30 Algonquian tribes were part of the powerful Powhatan Confederacy. Their land, called Tsenacommacah, covered much of the coastal Virginia area. Each of these 30+ tribes had its own name and chief (weroance). All paid tribute to a main chief, Powhatan, whose personal name was Wahunsenecawh. In the Powhatan tribes, leadership and property passed through the mother's family (a matrilineal system).

Other Algonquian groups, not part of the Powhatan Confederacy, included the Chickahominy and Doeg. The Chickahominy were independent. They governed themselves and were equal to the Powhatan. If Powhatan wanted them as warriors, he had to pay them in copper. The Accawmacke of the Eastern Shore and the Patawomeck were loosely connected to the Confederacy.

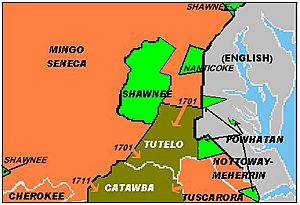

The Piedmont area was home to Siouan-speaking groups like the Monacan and Manahoac. The Iroquoian-speaking Nottoway and Meherrin lived in Southside Virginia. Other tribes lived in the mountains. The area beyond the Blue Ridge was sacred hunting grounds. This area became less populated during the Beaver Wars (1670–1700) due to attacks from the powerful Five Nations from New York.

When the English first started the Virginia Colony, the Powhatan tribes had about 15,000 people. Relations were not always peaceful. After Captain John Smith met Chief Powhatan in 1607, relations were fairly good. The Powhatan made agreements through family ties, often involving a female member. Powhatan sent food to the English, helping them survive.

When Smith left Virginia in 1609, relations worsened. Captain George Percy took over. Both sides raided each other for supplies. This led to the First Anglo-Powhatan War.

In 1613, Captain Samuel Argall captured Pocahontas, Powhatan's daughter. He wanted Powhatan to return English prisoners and tools. Peace was made after Pocahontas became Christian and married Englishman John Rolfe in 1614. This marriage connected the two peoples. Peace lasted until Pocahontas died in England in 1617 and her father in 1618.

After Powhatan's death, his brother Opitchapan became chief, then Opechancanough. Opechancanough planned a big attack on English settlements on March 22, 1622. He wanted to stop English expansion and drive them away. His warriors killed about 350-400 settlers. This was about one-third of the English population. The colonists called it the Indian massacre of 1622. Jamestown was saved because Chanco, a Native boy living with the English, warned them. The English fought back. Conflicts continued for 10 years until a shaky peace was made.

In 1644, Opechancanough planned a second attack. The English population had grown to about 8,000. His warriors again killed about 350-400 settlers. This led to the Second Anglo-Powhatan War. In 1646, Opechancanough was captured. A guard shot and killed him. His death marked the end of the Powhatan Confederacy's power. His successor, Necotowance, signed the first treaty with the English in October 1646.

The 1646 treaty set up a border between Native American and English settlements. People from each group needed a special pass to cross. The treaty defined the land open to English settlers:

- All land between the Blackwater and York rivers.

- Up to the navigable point of major rivers.

- A straight line from modern Franklin on the Blackwater to the Monocan village above the James River falls.

- Then to Fort Royal on the York (Pamunkey) river.

In 1658, English leaders worried settlers were taking Native lands. They passed a law saying colonists needed permission to settle on Native land. Land sales had to be public. The Wicocomico tribe sold their lands in Northumberland County to Governor Samuel Mathews in 1659.

Necotowance gave the English large areas of land. The treaty required the Powhatan to pay yearly tribute of fish and game to the English. It also set up reservation lands for the Native Americans. At first, all Native Americans had to wear a striped cloth badge in white areas or risk being killed. In 1662, this changed to a copper badge.

Around 1670, Seneca warriors from the New York Iroquois Confederacy took over the Manahoac territory. The Virginia Colony also expelled the Doeg. Virginia became neighbors with the Iroquois. The Iroquois hunted and raided in the Piedmont. Treaties in 1674 and 1684 recognized the Iroquois claim to Virginia above the Fall Line. At the same time, from 1671 to 1685, the Cherokee took western Virginia from the Xualae.

In 1677, after Bacon's Rebellion, the Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed. More Virginia tribes joined. It continued the yearly tribute payments. In 1680, Siouan and Iroquoian tribes in Virginia were added to the list of "Tributary Indians." More reservation lands were set up. The treaty made Virginia Native leaders subjects of the King of England.

In 1693, William and Mary College opened. One goal was to educate Virginia Native boys. Funds from England paid for their living and schooling. Only children from treaty tribes could attend. At first, no tribes sent their children. In 1711, Governor Spotswood offered to stop the yearly tribute payments if tribes sent their boys. This worked, and 20 boys attended that year. Later, fewer Native students attended. By the late 1700s, the funds were used elsewhere. The college was only for white students until 1964, when segregation ended.

Shifting Borders and Conflicts (1700s)

Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood (1710–1722) had a respectful policy toward Native Americans. He wanted to build forts along the frontier for Tributary Nations. These forts would act as buffers and trade centers. Native Americans would also receive Christian education. The Virginia Indian Company would control the fur trade. The first project, Fort Christanna, was successful. The Tutelo and Saponi tribes lived there. But private traders complained, and the monopoly ended by 1718.

Spotswood worked for peace with the Iroquois. In 1718, they agreed to give up land as far as the Blue Ridge Mountains and south of the Potomac. This was confirmed in 1721. This agreement caused problems later. The Blue Ridge seemed to be the border between Virginia Colony and Iroquois land. But the treaty said it was the border between the Iroquois and Virginia's Tributary Indians. White colonists thought they could cross the mountains freely, but the Iroquois disagreed. This dispute led to conflict in 1743 and was solved by the Treaty of Lancaster in 1744.

After this treaty, there was still confusion about whether the Iroquois had given up all claims south of the Ohio River. Also, the Shawnee and Cherokee nations claimed much of this land. The Iroquois recognized English rights to settle south of the Ohio in 1752. But the Shawnee and Cherokee claims remained.

In 1755, the Shawnee, allied with the French, attacked English settlers at Draper's Meadow (now Blacksburg). They killed five and captured five. The colonists called it the Draper's Meadow Massacre. The Shawnee captured Fort Seybert in 1758. Peace was made with the Treaty of Easton, where colonists agreed not to settle beyond the Alleghenies.

Fighting started again in 1763 with Pontiac's War. Shawnee attacks forced colonists to leave frontier settlements. The Crown's Proclamation of 1763 confirmed all land beyond the Alleghenies as Native American Territory. It tried to create a reserve for Native control. Shawnee attacks continued until 1766.

Many colonists believed the Proclamation Line was changed in 1768 by the Treaty of Hard Labour. This treaty set a border with the Cherokee across southwestern Virginia. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix also had the Iroquois sell their claims west of the Alleghenies and south of the Ohio. However, other tribes like the Cherokee, Shawnee, Lenape, and Mingo still lived there and were not part of the sale. The Cherokee border was changed again in 1770 by the Treaty of Lochaber. This was because European settlers had already moved past the 1768 line. The next year, Native Americans had to give up more land, extending into Kentucky. Meanwhile, Virginian settlements in West Virginia were strongly opposed by the Shawnee.

This conflict led to Dunmore's War (1774). Forts controlled by Daniel Boone were built along the Clinch River. By the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, the Shawnee and Mingo gave up their claim south of the Ohio. The Cherokee sold Richard Henderson land in extreme southwest Virginia in 1775. This sale was not recognized by the government or by the Chickamauga Cherokee war chief Dragging Canoe. But settlers began entering Kentucky. In 1776, the Shawnee joined Dragging Canoe's Cherokee in fighting the "Long Knives" (Virginians). Dragging Canoe led a raid on Black's Fort in 1776. Another Chickamauga leader, Bob Benge, raided western Virginia until he was killed in 1794.

In 1780, the Catawba Nation fled their reservation and hid in Virginia. They may have been in the mountains around Catawba, Virginia. They stayed there for nine months until American general Nathanael Greene led them back to South Carolina.

In 1786, after the US became independent, a Cherokee hunting party fought a Shawnee party in Wise County, Virginia. The Cherokee won, but both sides had heavy losses. This was the last battle between these tribes in Virginia.

Throughout the 1700s, several Virginia tribes lost their reservation lands. The Rappahannock lost theirs shortly after 1700. The Chickahominy lost theirs in 1718. The Nansemond sold theirs in 1792. After losing their lands, these tribes seemed to disappear from official records. Some members married people from other groups and blended in. Others kept their Native identity despite intermarriage. In their matrilineal systems, children of Native mothers were considered Native, no matter who their father was. By the 1790s, most surviving Powhatan tribes had become Christian and spoke only English.

Holding On (1800s)

During this time, Europeans continued to push Virginia Indians off their remaining reservations. By 1850, one reservation was sold. Another was officially divided by 1878. Many Virginia Native families held onto their individual lands into the 1900s. Only the Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes resisted the pressure and kept their communal reservations. These two tribes still have their reservations today.

After the Civil War, the reservation tribes began to reclaim their cultural identities. They wanted to show that Powhatan Indian descendants had kept their culture. This was important after slavery ended. Many white Virginians thought that mixed-race Native Americans were no longer culturally Native. But Native cultures often welcomed people of other backgrounds. If the mother was Native, her children were considered part of her clan and tribe.

The Fight for Identity (1900s)

In the early 1900s, many Virginia Native Americans began to reorganize into official tribes. They faced opposition from Walter Ashby Plecker, who was in charge of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics (1912–1946). Plecker was a white supremacist and believed in eugenics. He wanted to keep the white "master race" "pure." In 1924, Virginia passed the Racial Integrity Act. This law made the "one-drop rule" official. It said anyone with any known African ancestry was considered African or black.

Because of intermarriage and the lack of communal land for many Virginia Native Americans, Plecker believed there were few "true" Virginia Indians left. He did not understand that Native cultures had a long history of intermarriage and welcoming other peoples. Their children might have been mixed-race but still identified as Native.

The 1924 law defined a white person as having no more than one-sixteenth Native American ancestry. This was much stricter than before the Civil War. Before that, a person could be considered white with up to one-quarter African or Native American ancestry. Also, many court cases about race were decided based on how a person looked and acted, not detailed ancestry.

The Act was a leftover from slavery and Jim Crow segregation. It banned marriage between whites and non-whites. It only recognized "white" and "colored" (African ancestry). Plecker strongly supported the Act. He wanted to stop black people from "passing" as Virginia Indians. Plecker ordered local offices to only use "white" or "colored" on official records like birth certificates. He also told them to change the records of specific families he believed were black but trying to pass as Native.

During Plecker's time, many Virginia Native Americans and African Americans left the state to escape these strict rules. Others tried to stay hidden. Plecker's "paper genocide" (changing records to erase Native identity) lasted over two decades. It destroyed much proof that families continued to identify as Native.

The Racial Integrity Act was not repealed until 1967. This happened after the US Supreme Court case Loving v. Virginia. The court ruled that anti-interracial marriage laws were unconstitutional. The court said: "The freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race lies with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State."

In the late 1960s, two Virginia Native organizations applied for federal recognition. The Ani-Stohini/Unami applied in 1968, and the Rappahannock soon after. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) later said they lost the Ani-Stohini/Unami petition. They said many documents were lost during a protest in 1972. The Rappahannock tribe was recognized by Virginia. Today, at least 13 tribes in Virginia have asked for federal recognition.

After the Racial Integrity Act was repealed, people could change their birth certificates to show their Native identity. The state charged a fee for this. But in 1997, a law passed that allowed any Virginia Native American born in Virginia to change their records for free.

In the 1980s, Virginia officially recognized several tribes. These tribes had fought for recognition against racial discrimination. Because of their long history with Europeans, only two tribes still had reservation lands from colonial times. Not having reservations made it harder to prove their history, as outsiders thought they had blended into the majority culture. Three more tribes were recognized by the state in 2010.

Modern Native American Life (2000s)

Today, the total population of Powhatan Indians is estimated to be about 8,500–9,500. About 3,000–3,500 are members of state-recognized tribes. The Monacan Nation has about 2,000 members.

Organized tribes set their own rules for membership. Members usually pay dues, attend meetings, volunteer, and teach their children their history and traditions. They also represent their tribe at events like powwows. Most tribes keep some traditions from before European settlement. Native Americans are involved in modern society and jobs, but they also regularly take part in tribal activities. They try to balance their traditional culture with modern life.

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi are the only tribes in Virginia that have kept their reservations from the 1600s. These two tribes continue to pay their yearly tribute to the Virginia governor. This is required by the 1646 and 1677 treaties. Every year around Thanksgiving, they hold a ceremony to pay tribute, usually with a deer and pottery or a ceremonial pipe.

In 2013, the Virginia Department of Education released a 25-minute video called "The Virginia Indians: Meet the Tribes." It covers both historical and modern Native American life in the state.

Tribes Recognized by Virginia

Virginia passed a law in 2001 to create a process for state recognition of Native American tribes.

As of 2010, Virginia recognizes 11 tribes. Eight of them are related to historic tribes that were part of the Powhatan chiefdom. Virginia also recognizes the Monacan Nation, the Nottoway, and the Cheroenhaka (Nottoway), who were not part of the Powhatan group. Descendants of other Virginia Native American tribes still live in Virginia and elsewhere.

- Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Indian Tribe. State recognized in 2010; located in Courtland, Southampton County.

- Chickahominy Tribe. State recognized in 1983; located in Charles City County.

- Eastern Chickahominy Indians Tribe. State recognized in 1983; located in New Kent County.

- Mattaponi Tribe (also known as Mattaponi Indian Reservation). State recognized in 1983; located on the Banks of the Mattaponi River, King William County. The Mattaponi and Pamunkey have reservations from 17th-century treaties.

- Monacan Nation (formerly Monacan Indian Tribe of Virginia). State recognized in 1989; located in Bear Mountain, Amherst County.

- Nansemond Indian Tribal Association. State recognized in 1985; located in the Cities of Suffolk and Chesapeake.

- Nottoway Indian Tribe of Virginia. Recognized in 2010; located in Capron, Southampton County.

- Pamunkey Nation. Recognized in 1983; located on the Banks of the Pamunkey River, King William County. Federally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2015.

- Patawomeck Indians of Virginia. Recognized in 2010; located in Stafford County.

- Rappahannock Indian Tribe (I). State recognized in 1983; located in Indian Neck, King & Queen County.

- Upper Mattaponi Tribe. State recognized in 1983; located in King William County.

In 2009, the governor created a Virginia Indian Commemorative Commission. Its goal was to plan a monument in Capitol Square to honor Native Americans. Some plans have been made, but the statue is not yet installed.

Federal Recognition for Virginia Tribes

Various bills in Congress have proposed granting federal recognition to six non-reservation Virginia tribes. These include the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Upper Mattaponi, Rappahannock, Nansemond Tribes, and Monacan Indian Nation. These tribes have shown that their communities have continued over time. Federal recognition helps correct past injustices and recognizes their ongoing identity as Virginia Native Americans and US citizens. On January 29, 2018, President Donald Trump signed a law that granted federal recognition to these tribes. In May 2018, these tribes received $1.4 million in grants from the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

On May 8, 2007, the US House of Representatives passed a bill to recognize these six tribes, but the Senate did not pass it.

On March 9, 2009, the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2009 was sent to the House Committee on Natural Resources. The House approved the bill on June 3, 2009. It then went to the Senate, where it was approved by the Committee on Indian Affairs. However, the bill was stopped by a "hold" from Senator Tom Coburn. He believed tribal recognition should go through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Virginia tribes could not use the BIA process because many of their records were destroyed by Walter Plecker. The hold prevented the bill from becoming law.

On February 17, 2011, new bills for federal recognition were introduced in both the Senate and House.

On July 28, 2011, the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs approved the Senate version of the bill.

The two reservation tribes, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi, were not part of these bills. The Pamunkey were granted independent federal recognition by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 2015. The Mattaponi are also applying for federal recognition through the BIA.

Unrecognized Groups

More than a dozen groups claim to be Native American tribes but are not officially recognized by the federal or state government. Many of these are Cherokee heritage groups. One such group, the Ani-Stohini/Unami Nation, asked for federal recognition in 1968. In 1972, the Bureau of Indian Affairs said they lost the petition. The tribe filed a complaint that has not been resolved. In 1994, the tribe again submitted a letter to ask for recognition. Their request is still pending.

Suggested Reading

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |