Nansemond facts for kids

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Virginia | |

| Languages | |

| Algonquian (Historical), English | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional Religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nottoway, Chowanoke, Chesapeake, Pamunkey, Mattaponi, Chickahominy, Meherrin, Haliwa-Saponi |

The Nansemond are a Native American tribe. They are the original people of the Nansemond River area in Virginia. This river is about 20 miles long and flows into the James River. The Nansemond people lived in villages along both sides of the Nansemond River. They were skilled at fishing, gathering oysters, hunting, and farming. The name "Nansemond" itself means "fishing point" in the Algonquian language.

Over time, during the colonial period, the Nansemond were slowly pushed off their traditional lands. Despite this, they worked hard to keep their culture alive. In the late 1900s, they reorganized their tribe. Virginia officially recognized them as a tribe in 1985. Later, in 2018, the United States government also gave them federal recognition. Today, many Nansemond tribal members still live near their ancestral lands. These areas include Suffolk, Chesapeake, and nearby cities.

Contents

Understanding the Nansemond Language

The Nansemond language is thought to have been part of the Algonquian family. Many other tribes along the Atlantic coast spoke similar languages. However, only six Nansemond words have been saved over time. These few words are not enough to fully understand the language.

The six words were written down in 1901. They might have changed a little over the years. They are:

- nĭkătwĭn (one)

- näkătwĭn (two)

- nikwásăti (three)

- toisíaw’ (four)

- mishä́naw (five)

- marímo (dog)

Nansemond History and Early Encounters

The Nansemond people were part of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. This was a large group of about 30 tribes. It is believed that more than 20,000 people lived in this coastal area of Virginia. These tribes paid respect to a powerful leader called the Powhatan. The Nansemond lived along the Nansemond River, in a place they called Chuckatuck.

In 1607, English settlers led by John Smith arrived. They built a settlement called Jamestown on the north side of the James River. The Nansemond were careful and watchful of these new arrivals.

Early Conflicts with Colonists

The Jamestown settlers began exploring the Nansemond River in 1607. They were especially interested in the river's oyster beds. Relationships between the colonists and the Nansemond were already tense. Things got worse in 1609. A group of Jamestown settlers went to trade with the Nansemond for food. They never came back.

A search party found some Nansemond people. They were told the settlers had been sacrificed. In response, the colonists attacked Dumpling Island. This island was where the Nansemond chief lived. It also held the tribe's temples and sacred items. The colonists destroyed burial sites of tribal leaders and temples. They took valuable items like pearls and copper ornaments. These items were usually buried with important leaders.

By the 1630s, colonists started moving onto Nansemond lands. The two groups had very different ideas about owning land.

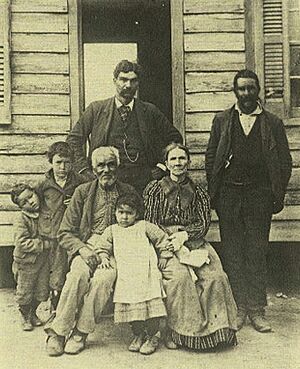

The Marriage of John Bass and Elizabeth

In the early 1600s, a colonist named John Bass married Elizabeth. She was the daughter of a Nansemond leader. Elizabeth was baptized into the Church of England, the main church of the colony. They married on August 14, 1638. John Bass was born in 1616 and passed away in 1699.

They had eight children together: Elizabeth, John, Jordan, Keziah, Nathaniel, Richard, Samuel, and William. Even though Elizabeth became Christian, she likely raised her children with Nansemond traditions. The Nansemond tribe followed a matrilineal kinship system. This means children were considered part of their mother's family and people. Some Nansemond people today trace their family history back to this marriage. Researchers believe that all current Nansemond members descend from this family.

As more colonists arrived, the Nansemond tribe eventually divided. Some Nansemond people became Christians and adopted European ways of life. They stayed along the Nansemond River as farmers. Other Nansemond, known as the "Pochick," fought an unsuccessful war in 1644. The survivors moved southwest to the Nottoway River. The government gave them a reservation there. By 1744, they had left that reservation. They went to live with the Nottoway Indians, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe, on another nearby reservation. The Nansemond sold their reservation in 1792. After this, they were known as "citizen" Indians.

The Nansemond Today

Today, the Nansemond tribe has about 400 members. They were recognized by the state of Virginia in 1984. They received federal recognition in 2018. The current chief of the tribe is Samuel Bass.

The tribe holds monthly meetings at the Indiana United Methodist Church. This church was started in 1850 as a mission for the Nansemond people. Each August, the tribe hosts an annual pow wow. This is a special gathering with dancing, singing, and celebrations. The tribe has also run a museum and gift shops.

Restoring Mattanock Town

In 2013, the Nansemond tribe reached an important agreement with the City of Suffolk. The city gave the tribe 100 acres (0.40 km2) of land. This land was part of a larger 1,100-acre (4.5 km2) riverfront park. It is located along the Nansemond River, which is their ancestral territory.

This agreement was the result of many years of talks. The City of Suffolk created a special group to study the project. This group, mostly made up of non-Indians, supported giving the land to the Nansemond. The tribe had to provide detailed plans for the project. This included drawings and documents for a non-profit group that would manage the land.

A researcher named Dr. Helen C. Rountree helped the tribe. Her research helped find the exact location of Mattanock Town. The tribe plans to rebuild the settlement of Mattanock. They will use archaeological and other research to make sure the longhouses and other buildings look historically accurate.

In November 2010, the Suffolk City Council agreed to return this land to the Nansemond. There were some delays in 2011 due to concerns about the development plans. But in August 2013, the land was officially transferred. That November, Nansemond tribal members gathered at the historic Mattanock Town site. They held a special blessing for the land.

The tribe will use this site to rebuild Mattanock. They also plan to build a community center, a museum, and a pow wow ground. They hope to attract visitors and share their rich heritage. This project took over ten years of planning and discussions between the tribe and the city.

Achieving Federal Recognition

The Nansemond and other Virginia tribes without their own land worked for many years to gain federal recognition. This finally happened in 2018 when the U.S. Congress passed a special bill. This bill recognized six tribes in Virginia. These included the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Eastern Chickahominy Indian Tribe, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe, the Rappahannock Tribe, the Monacan Indian Nation, and the Nansemond Indian Tribe.

These tribes had applied for federal recognition through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). This is a government office within the Department of Interior. However, they faced difficulties proving their cultural and political history. This was partly due to unfair treatment and discrimination by European Americans. Virginia was also a slave society, which made things even harder.

When Nansemond and other tribal people married white or African Americans, many European Americans assumed they were no longer "Indian." However, if the mother was Nansemond, she usually raised her children in their tribal traditions. In the early 1900s, Virginia passed a law called the "one drop rule." This law forced everyone to be classified as either white or "colored." "Colored" included anyone with any known African ancestry, even if they had other backgrounds or cultural ties.

Government officials often refused to recognize families who said they were Indian. They usually classified them as "black." This destroyed important historical records and made it hard to show continuous tribal identity. However, tribal members who were Catholic often continued to be recorded as Indian in church records for baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

Supporters of these tribes tried to pass a bill for federal recognition in 2003. It was called the "Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act." The bill was proposed again in 2009. By June 2009, it passed the House of Representatives. A similar bill was sent to the Senate. It was approved by a Senate committee in October 2009.

However, Senator Tom Coburn from Oklahoma delayed the bill. He believed the tribes should go through the BIA's regular process. But as mentioned, the Virginia tribes had lost valuable documents. This was because of Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This law required everyone to be classified as white or black. Walter Plecker, who was in charge of Virginia's Bureau of Vital Statistics from 1912 to 1946, changed many records. He changed the records of many Virginia-born tribal members from "Indian" to "colored." He did this because he decided some families were mixed race and enforced the "one-drop rule."

After more delays, the bill finally passed in January 2018. This was a huge step, giving six Virginia tribes the federal recognition they had sought for so long.

Images for kids

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |