Mattaponi facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Enrolled members:

Mattaponi, King William County, Virginia: 450 Upper Mattaponi, Hanover County, Virginia: 575 |

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Virginia Algonquian (historical) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pamunkey, Upper Mattaponi |

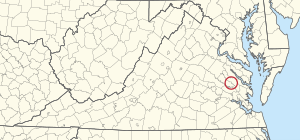

The Mattaponi tribe is one of only two Virginia Indian tribes in the Commonwealth of Virginia that owns reservation land. They have held this land since the colonial era. The main Mattaponi Indian Tribe lives in King William County on their reservation. This land stretches along the Mattaponi River, near West Point, Virginia.

The Mattaponi were one of six tribes that Chief Powhatan led in the late 1500s. They spoke an Algonquian language, like other tribes in the Powhatan Chiefdom. By the time the English settled Jamestown in 1607, the Powhatan chiefdom included more than 30 tribes.

A group of Mattaponi also lived outside the reservation in a small community called Adamstown. This area, located on the upper part of the Mattaponi River, has been known as Indian land since the 1600s. In 1921, this group officially formed the Upper Mattaponi Tribe. They are recognized by Virginia and own 32 acres (130,000 m²) of land in Hanover County. The Upper Mattaponi Tribe gained federal recognition on January 12, 2018.

The Mattaponi Indians are related to the Pamunkey Indians, who are also federally recognized. Both tribes share a similar culture and come from the same historical group.

Contents

The Mattaponi Tribe: A Rich History

Archaeologists believe that Native Americans have lived in what is now Virginia for up to 15,000 years. The historic tribes we know today likely formed in the 1300s and 1400s. These tribes belonged to three main language groups. Algonquian speakers lived along the coast. Siouan speakers lived in the central area. Iroquoian speakers were found in the backcountry and to the north. These language groups often shared cultures and identities.

Early Encounters: 17th Century

In 1607, the English explorer John Smith identified the Mattaponi by name. He noted they lived along the Mattaponi River. Another English writer, William Strachey, estimated they had about 140 warriors. This suggests the tribe's total population was around 450 people.

During the second Anglo-Powhatan War (1644–1646), the Mattaponi left their homes. They found safety in the highlands near Piscataway Creek. After the fighting ended, the tribe slowly returned to their homeland. In 1646, the Powhatan tribes signed their first treaty with the English. This treaty made the tribes "tributaries" to the English. It set aside reservation lands for some tribes. In return, the tribes had to pay an annual tribute of fish and game.

In 1656–1657, the Mattaponi Tribe's leaders signed peace treaties with the local English court. These treaties stated that tribal members should be treated equally to Englishmen in court. They also had the same civil rights.

Bacon's Rebellion and Peace Treaties

During Bacon's Rebellion, the Mattaponi were among several innocent tribes attacked by colonial forces. This rebellion was led by Nathaniel Bacon. Historians believe Bacon had a personal conflict with Governor Sir William Berkeley. However, other issues also caused the rebellion. These included tensions and raids from other local Virginia tribes. Bacon and his followers used these tribes as a target for their anger.

After the conflict, the Treaty of Middle Plantation was signed on May 29, 1677. Cockacoeske, the leader of the Pamunkey tribe, signed for several tribes, including the Mattaponi. The English called her "Queen of the Pamunkey." She became leader after her husband died fighting for the English in 1656. This treaty brought peace between the Virginia tribes and the English. More tribal leaders signed this treaty than the one nearly 30 years earlier. It confirmed the annual tribute payments. It also included the Siouan and Iroquoian tribes as "Tributary Indians." The government created more reservation lands. In return, the tribes had to accept the King of England as their ruler.

The Mattaponi and Pamunkey tribes still provide an annual tribute to the Governor of Virginia. This tradition continues from the treaties of 1646 and 1677.

Later History: 17th and 18th Centuries

In 1685, the Mattaponi, Pamunkey, and Chickahominy tribes attended a treaty meeting in Albany, New York. This meeting was an effort by colonial governments to end wars between the Iroquois and southern tribes. The Iroquois often raided Virginia, including areas along the Shenandoah and Ohio rivers. Settlers were caught in these conflicts. The constant warfare made it hard for peaceful colonial settlement in the backcountry.

The Mattaponi continued to live on their reservation throughout the 1600s and 1700s. However, colonists often moved onto tribal land during this time. A Baptist missionary working with the tribe in the 1700s recorded this. Governor Thomas Jefferson also noted in 1781 that settlers were taking Indian land. The Mattaponi always had their own tribal government. This government was separate from the Powhatan leadership, even though the tribe was part of the larger chiefdom.

Defending Their Land: 19th Century

The Mattaponi repeatedly defended their tribe and land from attempts to take their property. In 1812, local officials tried to take an acre of Mattaponi land for a dam. The tribe successfully stopped this effort. In 1843, some people claimed the Pamunkey and Mattaponi were no longer Indians. This was an attempt to remove them from their lands, but it also failed. Around the same time, historian Henry Howe reported two Indian groups living in King William County: the Pamunkey and the Mattaponi. In 1865, the Pamunkey Baptist Church was formed. Many Mattaponi attended this church over the years.

Throughout the 1800s, the Mattaponi Tribe had its own leaders. In 1868, the Mattaponi Tribe gave a list of its chiefs and members to the Governor. This list helped show who belonged to the tribe. Today, tribal members can trace their family history back to individuals on that list.

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi Tribes were the last parts of the Powhatan Chiefdom. Virginia treated them as one group until 1894. That year, the Mattaponi formally separated from the Pamunkey-led Powhatan Chiefdom. The state government then appointed five trustees to the Mattaponi Tribe.

The Mattaponi, like the Pamunkey, were excused from certain local taxes. The Mattaponi Tribe created its own rules for governing itself. They also built a school on their reservation.

Modern Times: 20th Century to Today

Throughout the 1900s, Virginia's Governors and Attorneys General have recognized the Mattaponi Tribe and its reservation. The tribe has also been mentioned often in books, articles, and newspapers.

The tribe has a traditional government called the Mattaponi Tribal Council. This council manages the reservation's affairs. They hold the land together but assign plots for members to use. The council also settles disagreements, maintains tribal property, and protects the tribe's interests. They work with local, state, and federal governments. The Mattaponi Tribe continues its obligations under the Treaty of Middle Plantation of 1677. They still give an annual tribute to the Governor of Virginia.

The Upper Mattaponi Tribe

The Upper Mattaponi Tribe was a group that settled on the upper part of the Mattaponi River. They did not live on the main reservation. Their community grew around a leading family named Adams. Their founder was likely James Adams, who helped translate between the Mattaponi and English from 1702 to 1727. In the 1800s, their settlement was known as Adamstown. The Upper Mattaponi tribe was not officially recognized until 1921. However, these tribal members are descendants of a group of Indians who lived near Passaunkack in the 1700s.

In 1921, the group officially formed as the Upper Mattaponi Tribe. They were recognized by the state of Virginia. After this recognition, the tribe faced challenges in keeping their culture strong. The state's Racial Integrity Act of 1924 made interracial marriage illegal in Virginia. Later laws required people to state their race on birth and marriage certificates. In an effort to control racial classifications, many Upper Mattaponi people were listed as black in official records. This happened because they had mixed ancestry. At the time, officials did not care how people identified culturally. This caused problems for their identity as a people because the records were incorrect.

In 1942, the Upper Mattaponi built the Indian River View Church. This church became the center of their Baptist community. Next to it is the Sharon Indian School. The first one-room school was built in 1917. Before that, Mattaponi children went to school with the Pamunkey. The state replaced the school with an eight-room building in 1952. It closed in the 1960s when official state racial segregation in public schools ended. The state returned the school to the tribe in 1987. They now use it as a community center.

In January 2022, the Upper Mattaponi Tribe bought its first official tribal housing unit. It is located in Central Garage, Virginia.

Mollie Holmes Adams was a member of the Upper Mattaponi Tribe. She was named one of the Virginia Women in History for 2010.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |