Chickahominy people facts for kids

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (Enrolled members) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Charles City County, Virginia (Chickahominy) | 840 |

| New Kent County, Virginia (Eastern Chickahominy) | 132 |

| Languages | |

| English, Algonquian (historical) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Native | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Piscataway, Yaocomico, Pamunkey, Mattaponi | |

The Chickahominy are a Native American tribe from Virginia. They mostly live in Charles City County, which is along the James River. This area is between Richmond and Williamsburg in the Commonwealth of Virginia. This part of the Tidewater area is near where they lived in the 1600s, before English colonists arrived. The tribe was officially recognized by the state of Virginia in 1983 and by the United States government in January 2018.

The Eastern Chickahominy tribe separated from the main Chickahominy tribe in 1983. They were also recognized as a separate tribe by Virginia that year, and by the federal government in January 2018. They are based in New Kent County, about 25 miles (40 km) east of Richmond. Neither tribe has an Indian reservation. They lost their original lands when colonists settled there in the 17th century. However, they have bought land for their communities to use.

Both tribes are among the 11 tribes that Virginia has officially recognized since 1983. The Chickahominy and Eastern Chickahominy tribes gained federal recognition when the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017 was passed on January 30, 2018.

Contents

History of the Chickahominy People

The Chickahominy ("The Coarse Ground Corn People") were one of many independent Algonquian-speaking tribes. They had lived in the Tidewater area for a long time. Their leaders were called mungai ("great men"). These leaders were part of a council of elders and religious leaders. The Chickahominy's original land was along the Chickahominy River. This river was named by the English after the tribe. Their land stretched from the river's mouth near Jamestown to what is now New Kent County, Virginia.

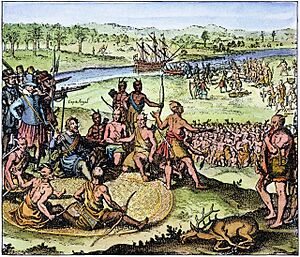

The Chickahominy met settlers from the first permanent English settlement at Jamestown in 1607. The tribe helped the English survive their first few winters. They traded food for English goods. The settlers were not ready for farming in this new land. The Chickahominy taught the English how to grow and store crops in the local conditions. By 1614, the tribe signed a treaty with the colonists. This treaty said the tribe would provide 300 warriors to fight the Spanish. Spain had a colony in Florida and along the lower East Coast.

Over time, the English settlements grew. This pushed the Chickahominy out of their homeland. The tribes and the English had already disagreed about land use. The Chickahominy expected to travel freely for hunting. The English wanted to keep some land as private property. After the Anglo-Powhatan Wars of 1644–46, the tribe had to give up most of its land to get a peace treaty. The tribe moved to reservation land set aside by the treaty. This land was in the Pamunkey Neck area, between the Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers. Another Virginia Algonquian tribe, the Pamunkey, also lived there.

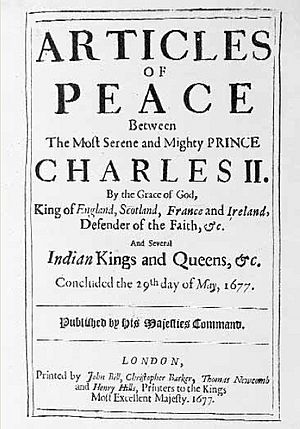

The Chickahominy stayed there until 1661. Then they moved again to the upper part of the Mattaponi River. But the English colony kept expanding onto their reserved lands. In 1677, the Chickahominy were among the tribes who signed a peace treaty with the King of England.

The people lost ownership of the last part of their reservation lands in 1718. However, they continued to live in the area for some time. Those who did not join with the Pamunkey and other tribes slowly moved back to New Kent County and Charles City County. This was closer to their original homeland. In the 20th century, descendants of these people organized to form the current Eastern Chickahominy and Chickahominy tribes. These movements happened before the end of the 18th century. Few records from this time survived because of major wars that disrupted the area.

The Chickahominy were independent. However, in the 17th century, they sometimes allied with Chief Powhatan. He led a large group of about 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes. Records show the Chickahominy tribe may have acted like a "police" force for Powhatan. They might have helped stop fights among other tribes in his group. In return, they got benefits, like trading with those tribes. As part of this alliance, it seems they were meant to be a "warrior force." They would protect Powhatan's tribes from less friendly or hostile tribes. This would give Powhatan's forces time to get ready. Some sources from the 1900s say the Chickahominy joined the Powhatan Confederacy in 1616. Others say they did not become part of this larger group until 1677. That's when Cockacoeske signed the Treaty of Middle Plantation. This treaty recognized her as the leader of the Chickahominy and several other tribes.

The Chickahominy Today

In the early 21st century, the Chickahominy tribe has about 840 members. Most of them live within a five-mile (8-km) area around their tribal center. This area is known as Chickahominy Ridge. Several hundred more members live in other parts of the United States. These places include California, Florida, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania. The tribe's current lands are about 110 acres (0.45 km2). This land is in the tribe's traditional territory in Charles City County. The tribal center on this land is where they hold their annual Powwow and Fall Festival.

The Chickahominy are led by a tribal council. This council has 12 men and women. It includes a chief and two assistant chiefs. These leaders are elected by the tribe's members through a vote. The current chief is Stephen Adkins. He used to be the Director of Human Resources for Virginia under Governor Tim Kaine. Wayne Adkins is an assistant chief, along with Reggie Stewart.

Most members of the Chickahominy Tribe are Christian. Many attend Samaria Baptist Church in Charles City County. This church was once called Samaria Indian Church. It was built on tribal grounds and used to be a school for the tribe's children. The church is right across from the tribal headquarters.

The Eastern Chickahominy

The people of the Chickahominy Tribe Eastern Division shared a history with the main Chickahominy tribe. This was true until the late 20th century. Then, they decided to create their own tribal government. Their community was based in New Kent County. Some members found it hard to always travel to Charles City County for tribal meetings. Others say the split happened because of disagreements about religious practices and how to use land. Family ties have kept the two tribes connected.

Today, the Eastern Chickahominy have about 132 members. They own about 41 acres (16.6 ha) of land. Tribe members have served in the United States military since World War I. The tribe helps its community as a non-taxable organization. This is supported by donations and dues paid by members.

Efforts to Gain Recognition

The Chickahominy tribe was federally recognized on January 11, 2018. U.S. Senators Tim Kaine and Mark Warner helped pass the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017.

Once the President signed this law, it gave federal recognition to six Virginia tribes. These tribes were the Chickahominy, the Eastern Chickahominy, the Upper Mattaponi, the Rappahannock, the Monacan, and the Nansemond. Since the 1990s, these tribes had been trying to get federal recognition through an act of Congress.

In March 2009, Representative Jim Moran from Virginia sponsored a bill. This bill aimed to give federal recognition to six Virginia Indian tribes that did not have reservations. These were the Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Nansemond, Rappahannock Tribe, Upper Mattaponi, and the Monacan Nation. By June, the bill passed the House of Representatives. A day after it was voted on in the House, a similar bill was sent to the Senate. The Senate sent this bill to their Committee on Indian Affairs. This committee approved the bill on October 22, 2009. On December 23, 2009, the Senate added the bill to its list of laws to consider. This was the furthest the bill had gone in the law-making process. The Commonwealth of Virginia and leaders of the Baptist Church, among other groups, supported this effort.

Senator Tom Coburn (R-OK) opposed the bill. He said he had "jurisdictional concerns." The senator believed that requests for tribal recognition should go through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). Moran and others supported the congressional process. This was partly because the Virginia tribes lost their continuous records. This happened due to unfair actions by the state government. Their records of Indian identity were destroyed because of changes from the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. These changes were ordered by Walter Plecker, who was the state registrar for the Bureau of Vital Statistics at that time.

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi tribes are also recognized by the state. They gained federal recognition through a different process, using the BIA's administrative process. They believed that living on and controlling their reservations continuously showed their long history as tribes.

To make its process better, the BIA announced changes to its rules in 2013. These changes include allowing tribes to show a shorter time period to prove their historical continuity. This could make it easier for tribes to show their recent historical connection and gain recognition. It could also speed up the bureau's review of their documents.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |