Croatan facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 64 - 80 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| North Carolina | |

| Languages | |

| Carolina Algonquian | |

| Religion | |

| Immortality of the Soul | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Roanoke |

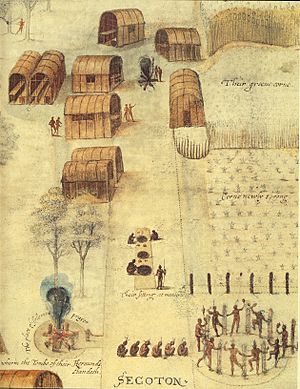

The Croatan are a small Native American group. They lived in the coastal areas of what is now North Carolina. They might have been part of the larger Roanoke people or worked closely with them.

Historically, the Croatan lived in Dare County. This area includes the Alligator River, Croatan Sound, Roanoke Island, Ocracoke Island, and parts of the Outer Banks, like Hatteras Island. Today, Croatan people mostly live in Cumberland, Sampson, and Harnett counties.

Their leaders were called werowances. This means "he who is rich." These chiefs controlled one to eighteen towns. The most powerful chiefs could gather seven or eight hundred fighters. Chiefs and their families were highly respected. However, they were not all-powerful. Leaders had to convince their followers that their ideas were good for the tribe. A chief's job was to share wealth with his tribe. If he could not do this, he would lose respect.

On June 30, 1914, the government looked into the rights of the "Cherokees," who were once known as Croatan Indians. The Croatan Indians were given rights. They were officially called "Croatan Indians." They also gained the right to have separate schools for their children. These schools would have committees of their own race. They could also choose their own teachers. This was based on the laws of North Carolina.

One expert on Algonquian languages thinks "Croatan" means "council town" or "talk town." This probably means it was where an important leader lived and where important meetings were held.

Contents

What did the Croatan people believe?

According to Thomas Harriot, Native Americans in coastal North Carolina believed in one main God. This God had always existed. They also believed this God made smaller gods to help create and rule the world. They thought that the soul lived forever.

When someone died, their soul either went to heaven to live with the gods. Or, it went to a place near the setting sun called Popogusso. There, it would burn forever in a huge fire pit. The ideas of heaven and hell helped common people respect their leaders. It also encouraged them to live a good life for their afterlife.

Conjurors and priests were special spiritual leaders. Priests were chosen for their knowledge and wisdom. They led the organized religion. Conjurors were chosen for their magical abilities. People believed conjurors had powers from a special connection with spirits, often from the animal world.

How did Europeans affect the Croatan?

When English settlers arrived, it changed how some tribes got along. Some Algonquian people wanted to work with the settlers. Others, like the Yamasee, Cherokee, and Chickasaw, fought against them. Later, this fighting led to the Yamasee War.

Tribes that worked well with settlers gained power. They got control of European trade goods. The English may have had better weapons. But the Native Americans' control over food and natural resources was very important. This helped them in conflicts with early settlers.

The Roanoke and Croatan tribes were thought to be on good terms with the English settlers of the Roanoke Colony. Wanchese, a Roanoke leader, even went to England with the English.

What happened to the Lost Colony?

Some people from the Lost Colony of Roanoke might have joined the Croatan. Governor White finally reached Roanoke Island on August 18, 1590. This was three years after he had last seen his family there. But he found his colony empty. The buildings had fallen apart.

The only clues about where the colonists went were the letters "CROATOAN" carved into a tree. Croatoan was the name of a nearby island (now Hatteras Island). It was also the name of a local Native American tribe. Roanoke Island was not the first choice for the colony. The idea of moving had been discussed. Before Governor White left, he and the colonists agreed on a plan. If they moved, they would carve a message into a tree. If they were forced to move, they would add a Maltese Cross. White found no cross. He hoped his family was still alive.

The Croatan, like other Carolina Algonquians, suffered from diseases. These included smallpox in 1598. These diseases greatly reduced their numbers. This made them weaker against colonial pressure. It is believed they stopped existing as a separate tribe by the early 1600s.

What are the theories about the "Lost Colony"?

Some people believe the Lumbee tribe in North Carolina are descendants of the Croatan. They think the Lumbee are also descendants of the survivors of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island. For over a hundred years, experts have studied where the Lumbee came from. Two main ideas remain.

In 1885, Hamilton McMillan, a local historian, suggested the "Lost Colony" theory. He based this on stories passed down by the Lumbee people. He also found strong clues. McMillan thought there was a link between the Lumbee and the English colonists who settled on Roanoke Island in 1587. He also linked them to the Algonquian tribes (including Croatan) living there at the time.

The colonists mysteriously disappeared soon after settling. They left few clues about where they went. McMillan's idea is that the colonists moved inland with the Native Americans. By 1650, they settled along the Lumber River. It is thought that today's Lumbee people are descendants of these two groups.

Other experts believe the Lumbee came from an eastern Siouan group called the Cheraws. In the 1600s and 1700s, several Siouan-speaking tribes lived in southeastern North Carolina. John R. Swanton, an early ethnologist, wrote in 1938 that the Lumbee were probably Cheraw descendants. He also thought they were related to other Siouan tribes in the area.

Today, historians like James Merrell and William Sturtevant agree with this idea. They suggest that the Cheraws, and survivors of other tribes, found safety in the Robeson County swamps. Their populations had been greatly reduced by wars and diseases. They sought refuge from both aggressive settlers and hostile tribes.

In 1914, Special Indian Agent O.M. McPherson listed names of the Lost Colony. Many names on the list were common Indian names in Robeson and Sampson counties at that time. Many of these last names belonged to surviving Croatan Indians. Later research in the 1900s showed that many Lumbee ancestors were mixed-race African Americans. These were free people in Virginia before the American Revolution. Their descendants moved to Virginia and North Carolina in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

These "free people of color" were often descendants of European men and African women. They lived and worked together in colonial Virginia. These connections have been found through old court records and land deeds. In Robeson County, they may have married Native American survivors. They then became part of the Native American culture.

What is the Croatan legacy today?

The Lost Colony Center for Science and Research has found English artifacts where the Croatan tribe once lived. These artifacts might show trade with the tribe. Or, they might show that Native Americans found them at the old colony site. The Center is doing a DNA study. They want to see if there are European family lines among Croatan descendants.

In 1890, about 100 Croatan Indians left Robeson County, North Carolina. They moved to southern Georgia. They built their own church and school. This helped them keep their identity. At that time, society had a clear line between "black" and "white." But the Croatan people saw themselves as "Indians." They lived outside of these racial rules.

The South tried to force the Croatan people into segregation. But the Croatan people of Bulloch County did not want this. Instead of obeying, they went back to Bulloch County. There, they could stay together as "Indians." The Croatan Indians made a home in a new place. It was unusual for Native Americans to keep their identity this way. They used the segregation of the Jim Crow South to build their own community. In 1910, North Carolina renamed the Croatan Indians in North Carolina to "Cherokee." They were called a branch of the Cherokee Nation.

A historical marker in Georgia tells their story. It says that in 1870, Croatan natives moved from Robeson County, North Carolina. They followed the turpentine industry to southeast Georgia. Many Croatan became farmers for the Adabelle Trading Company. They grew cotton and tobacco. The Croatan community built the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Adabelle. They also built a school and a cemetery nearby.

After the Adabelle Trading Company failed, the Croatan faced hard times. They also faced unfair treatment. Because of this, most of them returned to North Carolina by 1920.

Researchers from the University of Bristol, UK, are also digging on Hatteras Island. They are working with the Croatoan Archaeological Society. Hatteras Island was a main place for the Croatoan tribe. So far, they have found a large settlement from before and during European contact. They have also found old trash piles and European trade items.

Who were some notable Croatan people?

- Manteo disappeared after 1587. He was an important ambassador and mediator.