Battle of Soissons (1918) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Soissons |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Battle of the Marne, Western Front of World War I | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| At least 345,000 men, 478 tanks | At least 234,000 men, 210 aircraft | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

The Battle of Soissons was a major fight during World War I on the Western Front. It happened from July 18 to 22, 1918. This battle was part of a bigger attack by the Allied forces, including France, the United States, and Britain, against the German army.

The main goal was to cut off important supply routes for the German forces. These routes were a road and a railroad that went south from the city of Soissons. If these were cut, the Germans wouldn't be able to get supplies to their troops. This would force them to retreat. The Battle of Soissons was a turning point in the war. After this battle, the Germans were mostly on the defensive until the war ended.

Contents

- Why the Battle of Soissons Happened

- How the American Army Prepared for War

- Planning the Attack

- The Battleground

- Preparing for the Attack

- The Battle Begins

- What Happened Next

- Remembering the Battle

- Images for kids

Why the Battle of Soissons Happened

After Russia left World War I in March 1918, Germany gained many soldiers from the Eastern Front. This gave them a temporary advantage over the Allies. The Germans knew they had to win the war quickly before the United States could fully send its army to Europe.

German Spring Attacks of 1918

Starting in March 1918, Germany launched five big attacks, called the Kaiserschlacht (meaning "Kaiser's Battle"). These attacks aimed to break the Allied lines.

- The first two attacks, Michael and Georgette, targeted British armies. They tried to separate British and French forces and push the British back. They pushed the British back but failed to separate the armies or cut key supply lines.

- The third attack, Blücher-Yorck, was a trick to make France move its soldiers away from the British. This attack pushed the French back but didn't trick them into moving their main reserves.

- The fourth attack, Gneisenau, tried to straighten the battle lines. It also aimed to control a railway line to help supply German armies. This attack did not achieve its main goals.

- The fifth and final attack, Marneschutz-Reims, aimed to capture the city of Reims and its railway center. This would help the Germans with their supply problems. However, this attack failed quickly.

By the end of these attacks, the German army held two large areas deep inside Allied territory. One was in the British area, and the other was in the French area, including the Marne Salient.

How the American Army Prepared for War

When the American army joined the war in 1917, it was not ready. They had very few rifles, artillery guns, and machine guns. They also had very few airplanes. Even worse, America didn't have enough ships to transport many soldiers and supplies across the Atlantic.

The U.S. Congress passed laws to improve the military. However, not much happened until America officially entered the war. There was little effort to increase the army's size or to train and equip it properly.

Building a Stronger Army

American military leaders decided to create very large divisions, with about 28,500 soldiers each. This was twice the size of French, British, or German divisions. This was done for two reasons:

- Larger divisions could handle more losses and stay in battle longer.

- There weren't enough experienced officers to command many smaller divisions.

When American soldiers, called "doughboys," arrived in France, most were new recruits. They went through intense training. This included physical training and learning small unit tactics. They also practiced in trenches, learning how to use weapons and solve problems in trench warfare.

After this, they spent four weeks in a quiet part of the front line. Here, they got used to life at the front, listened for enemy activity, and saw their first combat. Before going into major battles, American soldiers also trained in offensive maneuvers with artillery and airplanes. This training focused on "open warfare" (moving attacks) rather than just trench fighting.

By July 1918, the U.S. had 26 divisions in France. Seven fully trained divisions were ready for battle near the Marne Salient. Many others were still training or had just arrived.

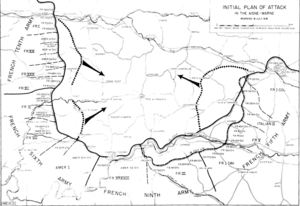

Planning the Attack

In May 1918, General John J. Pershing, who led the American forces, met with Ferdinand Foch, the Supreme Allied Commander. Pershing suggested an early counterattack against the German forces in the Marne Salient. Foch agreed that this was a good idea.

Later, Foch highlighted the importance of the roads and railways around Soissons. These were crucial for supplying four German divisions. Cutting these routes would severely hurt the Germans' ability to keep fighting.

General Charles Mangin, commander of the French Tenth Army, developed a plan to attack the plateau southwest of Soissons. From there, long-range guns could bombard the German supply network. Mangin also believed a surprise attack without much artillery preparation would work best.

On July 12, 1918, General Philippe Pétain, commander of the French armies, ordered immediate preparations for an attack. He stated that the main goal was to stop the Germans from using the Soissons supply network. The plan involved the French Tenth Army leading the main attack, supported by the French Sixth and Fifth Armies.

Pétain stressed the need for secrecy and set the attack for the morning of July 18. The American 1st and 2nd Divisions were assigned to the French Tenth Army.

On July 15, German forces crossed the Marne River. Pétain wanted to delay the Soissons attack to send reserves to the Marne. However, Foch quickly canceled this delay, insisting that the Soissons preparations must continue.

The Battleground

Looking east from the Forêt de Retz, the land was mostly open, rolling fields of wheat. Unlike other parts of the war, there were no complex trench systems here. The main target, the road and rail network south of Soissons, was about 7.5 miles (12 km) to the east, hidden by the sloping land.

The plateau had four deep, swampy ravines: Missy, Ploisy, Chazelle-Lechelle, and Vierzy. Villages made of strong stone buildings were located within and near these ravines. Large caves, dug for quarrying stone, also existed.

Two main roads crossed the area. The Soissons – Château-Thierry road ran south, directly across the attack path. The Soissons – Paris road ran southwest. These roads were the main supply lines for German troops in the Marne Salient.

The railroad ran south from Soissons, parallel to the Soissons – Château-Thierry road. It also served as a key supply route.

The American 1st Division would face Missy Ravine first, then Chazelle Ravine. The 2nd Division would deal with two parts of Vierzy Ravine. These ravines and villages were strong defensive positions for the Germans.

Preparing for the Attack

Foch wanted the attack to be a complete surprise. Strict rules were put in place to keep it secret. Soldiers were told to move only at night, light no fires, and report anything suspicious. To confuse the Germans, French artillery was kept far back, making it seem like a defensive setup. The two American divisions would rush to the front just before the attack began.

The American 1st and 2nd Divisions needed more soldiers after their previous battles. They were brought to full strength in early July. Just six days before the attack, both divisions were assigned to the newly formed American III Corps, which was then attached to the French Tenth Army.

On July 16, it was decided there would be no artillery bombardment before the French Tenth Army's attack. This was to ensure complete surprise. The attack would begin at 4:35 AM with a rolling barrage (artillery fire moving forward with the troops).

American 1st Division Moves In

On July 17, the American 1st Division moved closer to the front. At 9:00 PM, they began moving eastward through the forest. A thunderstorm started, turning the trails into deep mud. Soldiers had to march off the trails, using lightning flashes to see, holding onto the person in front to stay in line.

American 2nd Division's Difficult Journey

The American 2nd Division also faced a challenging journey. Their artillery brigade was ordered to move to a forest. The division's commander, Major General James Harbord, was frustrated because his units were scattered and he didn't know their exact destination or purpose. He found his command missing artillery and supplies, with no one able to tell him where they were going or when they would reunite.

Harbord and his staff had to plan the attack without seeing the area first. They didn't know if the units assigned to lead the attack would arrive on time. Many parts of the 2nd Division arrived west of the forest in the open on July 17. They moved into the forest, facing the same muddy conditions as the 1st Division. They had to push through other French units, tanks, and artillery. Many soldiers, having gone without sleep for 48 hours, fell asleep while marching.

Supplies were also a problem. There wasn't enough ammunition, and many machine guns were lost or arrived late. Some machine gun battalions went into the forest without their guns or ammunition. One battalion commander had to run the last 300 yards (274 meters) to catch up with the rolling barrage.

In contrast, the Moroccan 1st Division, which had been holding this part of the front, knew the terrain well. Their main task was to adjust their lines to make room for the two American divisions.

German Army Prepares

German documents from July 11 showed that deserters had warned them of a large buildup of Allied troops and a coming attack. The Germans expected the attack to be south of the Aisne River, aimed at their XIII Corps.

To strengthen their defenses, the Germans moved artillery and brought up reserve divisions. They set up strong defensive lines with fortified points. Starting July 12, German artillery began firing on Allied assembly areas to disrupt their preparations.

The Battle Begins

The American 1st Division was in the northern attack zone, with the French 153rd Division to their north. The American 2nd Division was in the southern zone, with the French 38th Division to their south. The Moroccan 1st Division was in between the two American divisions. Forty French air squadrons provided air support, mainly for scouting.

Attached to the American divisions were French artillery and tanks.

Day 1: Thursday, July 18, 1918

Just before the attack, German forces in the American 1st Division's area fired a weak counter-barrage. German soldiers had been warned by deserters about the attack.

At 4:35 AM, Allied artillery began firing on German positions.

American 1st Division's Advance

The attack started with a rolling barrage, moving forward 100 yards (91 meters) every two minutes. The infantry rushed forward to stay close to the barrage.

2nd Brigade's Fight

The 26th and 28th Infantry Regiments attacked without grenades, and their ammunition carriers were out of contact. The 28th Infantry faced heavy fire from its flanks as it approached Saint Amand Farm, a strong point in the French 153rd Division's area. A part of the 28th Infantry veered northeast and captured the farm by 7:00 AM.

The 2nd Battalion of the 28th Infantry then faced Missy Ravine. The French 153rd Division had been told to avoid this ravine. The ravine was full of German artillery, machine guns, and infantry. When two companies tried to cross, they were met with heavy machine-gun fire. French tanks supporting them were destroyed or sank in the swamp.

The American battalions decided to combine forces to cross the ravine. They waded through the waist-deep swamp, climbed the eastern bank, and captured all the German guns by 9:30 AM. They then formed a line east of Breuil, still under heavy machine-gun fire. One company of the 28th Infantry also captured about 500 German soldiers hiding in a cave.

By 11:00 AM, the 28th Infantry was deep in the French 153rd Division's sector. The French division was struggling to keep up, partly because of strong German defenses that fired into the American flank. The Germans considered this position key to defending Soissons. The French 153rd Division eventually took Saconin-et-Breuil and relieved the Americans.

The 26th Infantry captured Missy-aux-Bois by 9:00 AM. They advanced about 1 km (0.6 miles) east before being pinned down by machine-gun fire from the eastern side of the Soissons – Paris road.

1st Brigade's Push

The 1st Brigade advanced eastward behind the rolling barrage. The 16th Infantry's left flank became exposed because their advance was not slowed by ravines. The 18th Infantry kept pace with the 16th Infantry. The Moroccan 1st Division, on the 18th Infantry's right, kept pace initially but then slowed. As the 18th Infantry pushed forward, its right flank was exposed to machine-gun fire from Cravançon Farm. American soldiers from the 18th Infantry entered the Moroccan sector and captured the farm.

By 8:30 AM, both the 16th and 18th Infantry Regiments had crossed the Soissons – Paris road. They reformed and advanced through the Chaudun Position, taking the wheat fields north of Chaudun.

By 11:00 AM, the American 1st Division had captured both objectives that Foch had hoped for by the end of the day. They prepared to attack again at 5:00 PM. Artillery was moved forward, and supplies were distributed. However, the 2nd Brigade could not advance further due to heavy machine-gun fire from the Vauxbuin Position. The 1st Brigade reached its third objective, just north of Buzancy.

The Germans rushed all available reserves to the area. They set up new defensive positions with many machine guns west of the Soissons – Château-Thierry road. New artillery and fresh machine-gun units were also brought up.

Moroccan 1st Division's Role

The Moroccan 1st Division attacked between the American 1st and 2nd Divisions. They were supported by 48 tanks. The Legionnaires and Senegalese battalions advanced, eventually making contact with the American 18th Infantry.

The capture of Chaudun is debated. Some say the 18th Infantry took it, others say the 5th Marines. The American Battle Monuments Commission states that the 2nd Division helped capture the town, which was in the Moroccan division's zone.

By midday, the Moroccan 1st Division had advanced, helped by the American divisions on its flanks. However, their attack slowed because the Americans were moving into their sector. By the end of the day, the Moroccan division adjusted its lines to connect with the American 18th Infantry and the 5th Marines.

American 2nd Division's Attack

4th Marine Brigade's Fight

The 5th Marine Regiment was assigned a wide attack zone. They had to use two assault battalions instead of the usual three. Their starting line was deep in the Forêt de Retz.

As they emerged from the forest, about half of the Marines in the front line failed to turn in the planned direction. Some companies went too far south, crossing into the 9th Infantry's sector and helping clear Vauxcastille. A group of lost American Marines and soldiers were captured around noon near Soissons.

The 49th Company of the 1st Battalion lost contact with the Moroccan division. They came under fire from Maison Neuve and Chaudun. After heavy fighting, Marines and Senegalese fighters captured Chaudun around 9:00 AM, while other Marines cleared Maison Neuve.

Once Chaudun was taken, the Marine battalions regrouped and moved back into their sector. They stopped at the northern end of Vierzy Ravine, their second objective.

3rd Brigade's Advance

9th Infantry Regiment

The 9th Infantry Regiment managed to get most of its companies into position before midnight on July 17. The 1st Battalion led the attack. Because the Marines on their left were late, the 9th Infantry immediately faced flanking machine-gun fire. The 1st Battalion turned left to fight towards Verte-Feuille Farm. Around 5:45 AM, supporting tanks arrived, and elements of the 5th Marines helped capture the farm. The 1st Battalion continued northeast, fighting at Maison Neuve.

Company M of the 3rd Battalion, though supposed to be in reserve, advanced with the first wave. By 5:15 AM, Company M captured Beaurepaire Farm. They lost about 40% of their strength doing so.

After leaving Beaurepaire Farm, Company M faced artillery and machine-gun fire from across Vierzy Ravine. They crossed the ravine and climbed the opposite slope, reaching a point north-northeast of Vierzy by 9:20 AM.

23rd Infantry Regiment

The 23rd Infantry Regiment had the southernmost attack zone. The 2nd Battalion led the attack. They moved well until they reached Vauxcastille, where they met strong resistance. With their right flank exposed, parts of the 1st and 2nd Battalions moved into the French 38th Division's area. The 23rd Infantry surrounded Vauxcastille, and after heavy fighting, the Germans were driven out. Many Germans hid in nearby caves and were captured later.

Afternoon Attacks

By mid-afternoon, General Harbord informed his commanders of the attack plan for the next day. However, the starting positions for that attack had not yet been captured. The attack for the afternoon was set for 6:00 PM, but tanks were not ready until 7:00 PM. The infantry attacked when ready, and the tanks joined later.

The 9th Infantry, reinforced by the 5th Marines, attacked in the northern part of Vierzy Ravine. They faced resistance on the right. After advancing about 1 mile (1.6 km), they ran into heavy machine-gun fire from Léchelle Woods and Ravine on their left flank.

On the left flank, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, turned northeast. When the Germans fired an intense artillery barrage, the supporting tanks retreated, causing confusion. The Marines cleared out the defensive positions and continued east. This also helped the Moroccan attack, as the German southern flank was now exposed.

In the southern sector, some elements of the 23rd Infantry and Marines approached Vierzy in the morning, causing most German defenders to flee. But the fight for Vauxcastille lasted until almost 6:00 PM, so the 23rd Infantry could not advance in force. The Germans finally gave up Vauxcastille when it was surrounded by American and French tanks.

While the fight for Vauxcastille continued, the Germans reoccupied Vierzy and defended it fiercely. The 23rd Infantry attacked around 6:30 PM. Around 7:15 PM, a Moroccan battalion and 15 tanks supported the attack. The French 38th Division, attacking to the north and east, threatened to surround Vierzy, forcing the Germans to leave the town. Both brigades of the 2nd Division were ordered to move their command posts to Vierzy. After Vierzy fell, the 1st Battalion pushed 3 km (1.8 miles) east of the town.

German Army's Struggles

Despite knowing about the attack, the Germans were overwhelmed by its size. By noon, the German Ninth Army and part of the German Seventh Army had been pushed back.

To slow the Allied advance, the Germans ordered the 46th Reserve Division to set up defenses east of Buzancy. Other divisions were also moved to support the German Ninth Army.

As the situation worsened, German command ordered more divisions to the front. Troops were told they must hold the line at all costs. The German war diary noted that much of their artillery had been moved for another offensive, and many soldiers were sick with the Spanish flu. By the end of the day, the Allied penetration towards Soissons threatened to cut off the entire German Seventh Army. Orders were given for troops south of the Marne River to withdraw during the night.

Day 2: Friday, July 19, 1918

The attack continued on July 19, aiming to reach the same objectives as the previous day. The 6th Marines were brought in to replace the 5th Marines due to heavy casualties.

American 1st Division's Objectives

The 1st Division's goal for the day was to reach the line Berzy-le-Sec – Buzancy. The French 153rd Division was to take Berzy-le-Sec, and the Moroccan 1st Division was to take Buzancy. The rolling barrage started on time, but it was not as strong as expected.

The Soissons – Paris road was the first obstacle for the 2nd Brigade. The main German defense was the Vauxbuin Position, a large concentration of machine guns. Hill 166 was another strong point. Beyond the road lay Ploisy Ravine and Berzy-le-Sec, which overlooked the Soissons – Château-Thierry road and the railroad.

The 28th Infantry led the attack at 4:00 AM. They faced heavy fire from across the road and their northern flank. After several attempts, the 28th Infantry was forced to dig in and protect its exposed left flank. All supporting tanks were quickly put out of action.

The 28th Infantry attacked again at 5:30 PM. The 1st Battalion led the assault, reaching the objective just outside Berzy-le-Sec. The remaining battalions moved to support the 1st Battalion and fill the gap with the slow-moving French 153rd Division.

The 26th Infantry crossed the Soissons – Paris road but was stopped by fire from the front and the Vauxbuin Position. They also attacked at 5:30 PM, advancing 3 km (1.8 miles) and helping capture Ploisy.

1st Brigade's Gains

German infantry withdrew along the front of the 1st Brigade and the Moroccan 1st Division, allowing the 1st Brigade to gain ground. However, the Germans still defended stubbornly with artillery and machine-gun fire. The 16th Infantry's left flank was exposed to machine-gun fire because the 26th Infantry was held back. The 18th Infantry only managed to advance about 500 yards (457 meters) against strong machine-gun positions.

Moroccan 1st Division's Attacks

The Moroccan 1st Division launched two attacks, working around the flanks of Chazelle-Léchelle Ravine. They overcame resistance, creating a 2 km (1.2 miles) gap in the German lines between Parcy-et-Tigny and Charentigny by 1:00 PM.

The German 20th Division counterattacked late in the afternoon, causing the Moroccans to lose some ground. Villemontoire was recaptured by the Germans. During the evening, the Moroccans flanked the German position, driving them off. However, by the end of the day, the Germans had restored their defense of Villemontoire.

American 2nd Division's Relief

The 6th Marines replaced the 5th Marines due to heavy casualties. The French 38th Division attacked to the northeast, forcing the Germans to designate the Soissons – Hartennes-et-Taux highway as their next defensive position.

The attack orders for July 19 were delayed, pushing the start time from 4:00 AM to 7:00 AM. Twenty-eight French tanks were assigned to support the attack.

6th Marines in Action

The 6th Marines' assembly area was about 2.5 km (1.5 miles) from the front. They chose a hidden route, adding another 1 km (0.6 miles) to their march. They moved out when the rolling barrage started at 6:30 AM, failing to coordinate with the artillery.

The 1st Battalion went through Vierzy and up the east bank of the ravine, with tanks following. The Germans knew an attack was coming. The Marines were still 2 km (1.2 miles) from the front line when they began their advance.

As the 2nd Battalion moved east, a heavy artillery barrage began. They advanced slowly, keeping pace with the tanks. They faced machine-gun fire from the east and north. They stopped in abandoned German foxholes until 4:00 PM, under continuous fire.

The 1st Battalion advanced steadily with tanks, which drew most of the German artillery fire. They passed through the forward foxholes of the 23rd Infantry. One company stopped when its last tank was destroyed. Other companies moved up to fill gaps.

By 10:30 AM, the advance line was about 1 km (0.6 miles) east of the old front line, but under heavy artillery and flanking machine-gun fire. Ten minutes later, two companies reported 60% casualties.

Lieutenant Mason took command of what was left of one company. He led his men across open ground to capture an elevated strong point, Hill 160. This was the furthest advance by the American 2nd Division in the battle, about 700 yards (640 meters) short of the Soissons – Château-Thierry road.

The 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines, started the day with 36 officers and 850 men. By 8:00 PM, only 20 officers and 415 men remained. It was impossible to move wounded soldiers or move between positions without drawing fire.

By the afternoon of July 19, General Harbord decided the 2nd Division could hold its position but could not advance further. He requested that the 2nd Division be relieved by a fresh division. This request was approved. The French 58th Colonial Division moved up to relieve the American 2nd Division during the night of July 19/20.

The American 2nd Division's attack on July 19 had reached a point where artillery could not support it unless the artillery was moved forward. The attack was also held up on the right flank, and the left flank was threatened.

German Army's Dire Situation

The German Ninth Army's morning report showed their desperate situation. Two of their divisions were almost completely destroyed. Only remnants remained on the front line. Other divisions were split or far from the front. The transfer of XIII Corps from the Ninth Army to the Seventh Army was completed.

The Seventh Army reported heavy losses in soldiers and equipment. By evening, the Allies had advanced significantly. The single supply line to the German front in the salient was now within range of Allied artillery. This, combined with the threat to their rear, forced the Germans to decide to withdraw. Orders were issued to begin the withdrawal during the night of July 19/20.

Day 3: Saturday, July 20, 1918

During the night, rolling kitchens brought food and water to the front, but many were destroyed by German artillery fire. German artillery also fired gas shells.

Foch ordered the battle to continue on July 20, aiming to destroy enemy forces south of the Aisne and Vesle rivers. The Tenth Army would capture plateaus north of Fère-en-Tardenois, with the Sixth Army supporting.

The American 1st Division's front line faced northeast. The 28th Infantry Regiment was in Ploisy Ravine, maintaining contact with the French 153rd Division. The 26th Infantry Regiment faced north, linking with the 28th Infantry and 1st Brigade. The 1st Brigade's front line ran from Ploisy Ravine south to Chazelle, connecting with the Moroccan 1st Division.

The city of Soissons is in the northeast corner of a high plateau. Several elevated positions overlook Soissons and its approaches. Berzy-le-Sec sits on one of these positions, overlooking the railroad and highway in the valley. Controlling Berzy-le-Sec was key to controlling the valley.

Because the French 153rd Division failed to take Berzy-le-Sec, Mangin changed the boundary, giving the task to the American 1st Division. The attack was scheduled for 2:00 PM.

The Moroccan 1st Division attacked late in the morning, with the American 1st Brigade moving with them. They met little resistance until they reached a bluff overlooking the railroad. The Moroccans pushed some units across the railroad. The 1st Brigade also moved parts of two battalions east of the railroad.

The plan called for a light supporting barrage for the attack on Berzy-le-Sec. Colonel Conrad Babcock argued that without a heavy barrage, his troops would suffer heavy losses crossing open ground under heavy fire. However, the plan was not changed.

Three small infiltration squads tried to enter Berzy-le-Sec from the north. They reached the outskirts but couldn't enter until after dark due to heavy machine-gun fire. A battalion of the 26th Infantry attacked from the south but was quickly stopped by devastating German artillery.

Babcock planned a night infiltration, but it was canceled because an intense artillery barrage was scheduled for 4:45 AM.

Although Berzy-le-Sec was not taken on July 20 by the Allies, German records indicated the town was not in German hands at 11:00 AM. Late in the afternoon, Mangin, Bullard, and Pershing insisted on capturing Berzy-le-Sec. Orders were issued to renew the attack the next morning. The American 1st Division would be relieved by the Scottish 15th Division after the attack.

Further south, the 1st Brigade was still west of the Soissons – Château-Thierry road. The Moroccans crossed the railroad and were relieved by the French 87th Division. The French 58th Division completed its relief of the American 2nd Division and planned its attack for July 21.

Day 4: Sunday, July 21, 1918

During the night, the Moroccan 1st Division was relieved by the French 87th Division. A French regiment was sent to reinforce the French 153rd Division to protect the American 1st Division's left flank during their attack on Berzy-le-Sec.

The American 1st Division's attack plan for July 21 was the same as the previous day, with a rolling barrage starting at 4:45 AM. However, the French 69th Division commander said he couldn't attack so early and demanded a three-hour artillery preparation. This meant the American 1st Division had to coordinate with the French 87th Division (attacking at 4:45 AM) and the French 153rd Division (attacking at 8:30 AM).

General Buck, commanding the 2nd Brigade, spent the night explaining the attack orders to his commanders. The attack would be in three waves. The Germans were reinforcing their positions with the German 46th Division.

To the south, a heavy artillery preparation began at 4:30 AM, followed by the French 87th Division's ground attack at 6:00 AM. By 6:45 AM, the Germans were driven across the Soissons – Château-Thierry road. Buzancy changed hands several times during the day. The German 5th Division arrived mid-afternoon but failed to retake the high ground.

Buck assigned the 28th Infantry the task of taking Berzy-le-Sec and advancing to the center of the ravine east of town. The 26th Infantry was to take the Sucrerie (sugar factory). This would give the Allies firm control of Berzy-le-Sec and a view of Soissons.

Minutes before the attack, German artillery opened fire. Lieutenant Sorenson, who was to lead the first wave, was wounded. Lieutenant John Cleland took command.

A planned artillery preparation on Berzy-le-Sec at 5:30 AM never happened. The rolling barrage for 8:30 AM was ten minutes late. As the first wave crossed the wheat fields, German artillery and machine guns opened fire.

The assault paused before reaching the village. Buck rushed forward to see what was happening. He found that Cleland had been wounded but refused to leave. Buck then noticed the second wave was far behind and rushed back to get them moving. He gathered the remaining soldiers, mostly machine-gunners, and directed them to the edge of the ravine.

As the assault line approached Berzy-le-Sec, enemy artillery fire increased. The first wave pushed into heavy machine-gun and rifle fire from within the town. German guns fired directly at the attackers, but the line held. By 9:15 AM, the 2nd Brigade had taken Berzy-le-Sec, with the Germans retreating across the Crise River. The 2nd Brigade pursued them but stopped at the western bank of the river. By 10:15 AM, they controlled the railroad and had achieved their final objective.

The 2nd Brigade's left flank was exposed because the French 153rd Division had not advanced as far. The Germans pinned down the 28th Infantry with flanking fire and long-range machine-gun fire.

After Berzy-le-Sec was taken, Buck learned that the 26th Infantry's advance on the Sucrerie was stopped. Even with assistance, the 1st Brigade could not capture the Sucrerie. By the end of the day, the 2nd Brigade's line ran from the heights north of Berzy-le-Sec, along the Soissons – Château-Thierry road south of the Sucrerie. The 1st Brigade pushed east of the road, stopping in the woods west of Buzancy Château.

Day 5: Monday, July 22, 1918

The Scottish 15th Division was not in position to relieve the American 1st Division, so the 1st Division remained on the front line on July 22. There was no major fighting, but the 26th Infantry advanced its line east of the Sucrerie to eliminate sniper fire and straighten the front. Liaison was maintained with the French divisions on their flanks. The line on the right of the American 1st Division remained north and west of Buzancy, as they could not take the town.

Priority was given to removing the wounded and burying the dead. German aircraft flew low, attacking targets. German artillery shelled the front lines. In the afternoon, advance parties from the French and British relief forces arrived to plan the relief for that night.

During the night of July 22/23, the Scottish 15th Division and the rest of the French 69th Division moved forward to relieve the American 1st Division.

What Happened Next

At dawn on July 23, the Scottish 15th Division continued the attack eastward. The American 1st Division's artillery remained to provide support. However, it was hard to find the infantry's front line, so the rolling barrage was too far ahead to protect the attacking troops. The Scottish 15th Division suffered heavy losses and made little progress.

With their main supply route to the Marne Salient cut and the Soissons rail hub within range of Allied artillery, the Germans found it very difficult to supply their armies. Faced with the risk of their forces being trapped, the Germans had no choice but to give up their gains.

After strong German resistance and fierce fighting, Soissons finally fell to the Allies on August 2, 1918. When the Aisne-Marne campaign officially ended on August 6, 1918, the front line ran straight along the Vesle River from Soissons to Reims.

By the evening of July 22/23, 1918, the Allies had won a decisive victory. Two major German offensives, Operation Hagen and Operation Kursfürst, were canceled because of this battle. Germany never regained the advantage and remained on the defensive until the war ended.

Remembering the Battle

Oise-Aisne American Cemetery

The Oise-Aisne Cemetery is the second largest American World War I cemetery in Europe. It holds 6,012 graves. The cemetery has long rows of headstones on a gentle slope. It is divided into four sections by wide paths lined with trees and roses.

The memorial is a curving structure made of rose-colored stone. It has a chapel and a map room. The Walls of the Missing list the names of 241 soldiers who were never found. Rosettes mark the names of those later identified. The map room has a map showing the military operations in the region in 1918.

Sgt. Joyce Kilmer, a famous American poet, is buried here. He was killed by a sniper on July 30, 1918.

1st Division Battlefield Monument

The 1st Division Battlefield Monument was built by the 1st Division. It is west of Buzancy on the Soissons - Château-Thierry road. The monument has a concrete base with the names of the dead engraved on bronze plates. On top is a stone eagle on a pedestal, with a replica of the 1st Division's shoulder patch.

2nd Division Battlefield Marker

The 2nd Division Battlefield Marker is near the Soissons - Paris road, about 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Beaurepaire Farm. It is a concrete boulder with the 2nd Division's symbol engraved in bronze. Nearby is another marker showing the furthest advance of the German Army in 1918.

Images for kids

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |