Stephen Breyer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stephen Breyer

|

|

|---|---|

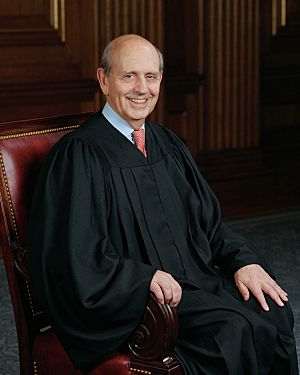

Official portrait, c. 2006

|

|

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office August 3, 1994 – June 30, 2022 |

|

| Nominated by | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Harry Blackmun |

| Succeeded by | Ketanji Brown Jackson |

| Chief Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit | |

| In office March 1990 – August 3, 1994 |

|

| Preceded by | Levin H. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Juan R. Torruella |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit | |

| In office December 10, 1980 – August 3, 1994 |

|

| Nominated by | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Sandra Lynch |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Stephen Gerald Breyer

August 15, 1938 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Joanna Hare

(m. 1967) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Charles Breyer (brother) |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1957–1965 |

| Rank | Corporal |

| Unit | Army Strategic Intelligence |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War |

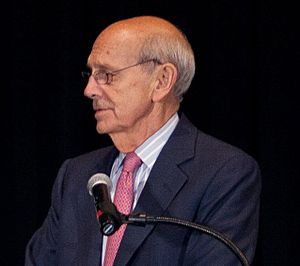

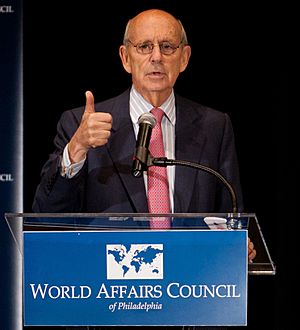

Stephen Gerald Breyer (born August 15, 1938) is an American lawyer and retired judge. He served as an Associate Justice on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1994 until he retired in 2022. President Bill Clinton chose him for the role. Breyer was known for his generally liberal views on the Court. After retiring, he became a professor at Harvard Law School.

Breyer was born in San Francisco. He studied at Stanford University and the University of Oxford. He then graduated from Harvard Law School in 1964. After working for Justice Arthur Goldberg, Breyer taught law at Harvard from 1967 to 1980. He was an expert in administrative law, which is about how government agencies work. He also held other important jobs, like helping with the Watergate scandal investigation in 1973. In 1980, Breyer became a federal judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. In his 2005 book, Active Liberty, Breyer explained his legal ideas. He believed judges should make decisions that encourage people to take part in government.

On January 27, 2022, Breyer and President Joe Biden announced Breyer's plan to retire. On February 25, 2022, Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson to take his place. She was a judge and one of Breyer's former law clerks. Breyer stayed on the Supreme Court until June 30, 2022, when Jackson officially became a justice. Breyer wrote important majority opinions in cases like Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. and Google v. Oracle. He also wrote notable disagreements, questioning the fairness of the death penalty in cases like Glossip v. Gross.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Stephen Breyer was born on August 15, 1938, in San Francisco, California. His parents were Anne and Irving Breyer. His family was middle-class and Jewish. His father was a lawyer for the San Francisco Board of Education. Stephen and his younger brother, Charles R. Breyer, were active in the Boy Scouts of America. Both became Eagle Scouts.

Breyer went to Lowell High School. He was part of the debate team. He often debated against people who would later become famous, like future California governor Jerry Brown.

College and Law School

After high school in 1955, Breyer studied philosophy at Stanford University. He graduated in 1959 with high honors. He then received a Marshall Scholarship to study at Magdalen College, Oxford, in England. He earned another degree there in 1961.

He returned to the U.S. to attend Harvard Law School. He was an editor for the Harvard Law Review. He graduated in 1964 with a law degree, magna cum laude.

Breyer served eight years in the United States Army Reserve. This included six months of active duty in Army Strategic Intelligence. He reached the rank of corporal and was honorably discharged in 1965.

In 1967, Breyer married Joanna Freda Hare. She is a psychologist. They have three adult children: Chloe, Nell, and Michael.

Legal Career

After law school, Breyer worked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg from 1964 to 1965. He also briefly helped the Warren Commission. Then, he spent two years in the U.S. Department of Justice's Antitrust Division.

In 1967, Breyer returned to Harvard Law School as a professor. He taught there until 1980. He was known as a top expert in administrative law. He wrote important books about how government rules affect businesses. One of his famous writings was "The Uneasy Case for Copyright" in 1970. He also taught as a visiting professor in Australia and Italy.

While teaching, Breyer took time off to work for the U.S. government. He was a special prosecutor for the Watergate scandal in 1973. He also worked for the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary from 1974 to 1980. He helped Senator Edward M. Kennedy pass the Airline Deregulation Act. This law changed how airlines were regulated.

U.S. Court of Appeals (1980–1994)

On November 13, 1980, President Jimmy Carter nominated Breyer to the First Circuit. The United States Senate confirmed him on December 9, 1980. He officially became a judge on December 10, 1980.

From 1980 to 1994, Breyer served as a judge on this court. He became the court's Chief Judge from 1990 to 1994. As chief judge, he helped design and build a new federal courthouse in Boston. This sparked his interest in architecture.

Breyer was also a member of the Judicial Conference of the United States and the United States Sentencing Commission. On the sentencing commission, he helped create the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. These rules aimed to make criminal sentences more consistent across the country.

Supreme Court (1994–2022)

In 1993, President Bill Clinton considered Breyer for a Supreme Court seat. Clinton eventually chose Ruth Bader Ginsburg for that position.

When Justice Harry Blackmun retired in 1994, Clinton again looked for a new justice. After several other people declined the nomination, Clinton decided to nominate Breyer. Senators Ted Kennedy and Tom Harkin strongly supported Breyer. Clinton nominated him as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court on May 17, 1994. The Senate confirmed Breyer on July 29, 1994, by a vote of 87 to 9. He officially joined the Court on August 3.

During his 28 years on the Court, Breyer wrote 551 opinions.

Key Cases and Opinions

Breyer wrote important opinions on many different legal topics.

Laws About Medical Procedures

In 2000, Breyer wrote the main opinion in Stenberg v. Carhart. This case struck down a Nebraska law about certain medical procedures. On June 29, 2020, he wrote the main opinion in June Medical Services v. Russo. This ruling struck down a Louisiana law that required doctors performing these procedures to have hospital privileges nearby. Breyer used a test he created in an earlier case to decide this. In 2022, he disagreed with the majority in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization. This decision overturned Roe v. Wade, which had established a constitutional right to these procedures.

Census and Immigration

In Department of Commerce v. New York (2019), Breyer was part of the majority. The Court ruled that the Census Bureau did not follow proper steps when trying to add a citizenship question. Breyer believed the decision was "ill considered." He felt it did not properly consider the risk of undercounting people.

On December 18, 2020, Breyer disagreed with the Court's decision in Trump v. New York. He argued the Court should have stopped the Trump administration's attempt to exclude undocumented immigrants from the census count.

Copyright Law

Breyer often expressed concerns about long copyright terms. In Eldred v. Ashcroft (2003), he disagreed with extending copyright terms by 20 years. He argued it was almost like giving endless copyright, which he felt went against the Constitution's goal of promoting creativity. He believed it would not encourage more artists to create new works.

In Google v. Oracle (2021), Breyer wrote the majority opinion. The Court decided that Google's use of certain Java computer code was fair use. He explained that using this code was essential for programmers to use the Java language.

Concerns About the Death Penalty

In 2015, Breyer disagreed with the majority in Glossip v. Gross. He questioned whether the death penalty itself was constitutional. He wrote that it was "highly likely" to violate the Eighth Amendment. He repeated this view in 2020, suggesting the Court should fully examine the issue.

Free Speech

On June 18, 2015, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans. He ruled that license plates are considered government speech. This means they can be regulated more than private speech. He noted that governments have historically used license plates to send messages.

On June 23, 2021, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.. This case was about schools regulating student speech that happens off-campus. He said that while schools can regulate some off-campus speech, there are limits. He noted that using profanity on social media did not cause enough disruption to justify punishment in that specific case.

Protecting Defendants

On June 21, 2011, Breyer wrote for the majority in Turner v. Rogers. This case was about whether people facing civil contempt charges need a lawyer. He said that while a lawyer isn't always required, other safeguards must be in place. These safeguards ensure fairness, like providing financial information or explaining legal terms.

On June 22, 2015, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in Kingsley v. Hendrickson. He ruled that people held before trial only need to show that police force was "objectively unreasonable." They don't need to prove the officers intended to use excessive force.

Native American Law

On November 27, 2001, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in Chickasaw Nation v. United States. This case was about whether Native American tribes had to pay taxes on gambling operations. He ruled that federal law did not give tribes the same tax exemption as state lotteries.

On April 19, 2004, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in United States v. Lara. The Court ruled that both tribal governments and the federal government can prosecute non-member Native Americans for the same charges without violating the Double Jeopardy Clause. This is because Native Nations are considered separate sovereign entities.

Environmental Protection

In Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc. (2000), Breyer was part of the majority. The Court ruled that people who couldn't use a river due to pollution had the right to sue the polluters.

On April 23, 2020, Breyer wrote the majority opinion in County of Maui v. Hawaii Wildlife Fund. The Court ruled that Maui County needed a permit under the Clean Water Act. This was required to release polluted groundwater into the ocean. Environmental groups saw this as a victory.

On July 31, 2020, Breyer disagreed when the Supreme Court allowed construction of a wall at the U.S.-Mexico border to continue. Environmental groups argued the wall would harm wildlife. Breyer felt the Court's decision might act as a "final judgment" on the issue.

Healthcare Laws

Breyer generally voted to support the Affordable Care Act (ACA). He wrote the majority opinion in California v. Texas (2021). The Court ruled that Texas and other states did not have the right to sue against the ACA's individual mandate. Breyer explained that the states could not show they were directly harmed by the law.

Voting Rights and Fair Districts

On April 28, 2004, Breyer disagreed in Vieth v. Jubelirer. The Court decided that political gerrymandering (drawing unfair voting districts) was not something courts should decide. Breyer believed that sometimes unfair gerrymandering could harm democracy.

In June 2019, Breyer again disagreed in Rucho v. Common Cause. The Supreme Court decided that gerrymandering is a political issue, not a legal one for the courts.

Breyer wrote the majority opinion in Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama. This case ruled that claims of racial gerrymandering must be looked at district by district. It struck down four of Alabama's state Senate districts as unconstitutional.

Breyer also disagreed with decisions that made it harder to vote. He joined dissents in cases that limited voting access, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Retirement and Post-Retirement

After the 2020 elections, some people urged Breyer to retire. They wanted President Biden to appoint a younger liberal justice. Breyer said he wanted to retire before his death. He mentioned a conversation with Justice Antonin Scalia about not wanting a successor to undo his work.

On January 26, 2022, news outlets reported Breyer's plan to retire. He confirmed this with President Biden on January 27. On February 25, Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson to replace him. Jackson was a former clerk for Breyer. The U.S. Senate confirmed Jackson on April 7, 2022. Breyer's last opinion before retiring was in Torres v. Texas Department of Public Safety. He retired on June 30, 2022. His retirement left only one military veteran, Samuel Alito, on the Supreme Court.

On July 2, 2022, it was announced that Breyer had been appointed a professor at Harvard Law School. He had previously studied and taught there. In May 2024, Breyer received an honorary law degree from Yale University. This recognized his contributions to law and his nearly three decades on the Supreme Court.

As a retired Supreme Court justice, Breyer can still serve as a judge in lower federal courts. He returned to the bench in 2025 in the First Circuit Court of Appeals. This was the court where he was a judge before joining the Supreme Court.

Judicial Philosophy

Breyer is known for his pragmatic approach to legal interpretation. This means he focused on the practical results and the purpose of laws. Legal experts like Cass Sunstein described his view as making the law "more sensible." Breyer also criticized originalism, a different legal philosophy.

Breyer consistently supported laws related to women's health choices. He also believed that courts could use foreign and international law as helpful guides, though not as strict rules. He often respected the decisions of law enforcement and Congress. He voted to overturn laws passed by Congress less often than any other justice since 1994.

Breyer's deep knowledge of administrative law influenced his work. He strongly defended the Federal Sentencing Guidelines. He disagreed with a strict interpretation of the Sixth Amendment. This amendment says that all facts needed for criminal punishment must be decided by a jury. Breyer's practical approach was often seen as a contrast to Justice Antonin Scalia's textualist philosophy.

Breyer explained that he used six tools to understand the meaning of a law:

- The exact words of the law (text)

- Its historical background

- Past court decisions (precedent)

- Long-standing customs (tradition)

- The goal or reason for the law (purpose)

- The effects of different interpretations (consequences)

He noted that only the last two tools set him apart from textualists like Scalia. Breyer argued that considering purpose and consequences helps make legal interpretation more objective. It also ensures decisions fit the law's original goal.

Active Liberty

Breyer explained his legal philosophy in his 2005 book, Active Liberty: Interpreting Our Democratic Constitution. In this book, Breyer urged judges to interpret laws based on their purpose. He also wanted judges to consider how the results of their rulings fit those purposes. The book was seen as a response to Justice Antonin Scalia's 1997 book, which focused only on the original meaning of legal texts.

In Active Liberty, Breyer argued that the Framers of the Constitution wanted to create a democratic government. This government would give its citizens the most freedom possible. Breyer talked about two types of freedom. One is "freedom from government control," which he called "modern liberty." The other is the "freedom to participate in government," which he called "active liberty." Breyer believed that "active liberty" was very important to the Framers. He argued that judges should make decisions that support this idea of democratic participation.

Some people have questioned Breyer's ideas in the book. They argued that the Constitution does not always put "active liberty" above "modern liberty." Others suggested that Breyer might choose the outcome he prefers, then find a purpose to support it.

However, others defended Breyer. They pointed out that he often voted to support laws passed by Congress. Breyer himself admitted that his approach would not solve every legal debate. He also said that respecting the democratic process does not mean judges should ignore the limits set by the Constitution. He noted that important changes, like ending slavery or ensuring "one person, one vote," did not come from democratic means alone. Instead, courts helped overturn unfair laws to protect civil rights.

Other Books

In 2010, Breyer published another book, Making Our Democracy Work: A Judge's View. In it, he again discussed the six tools judges use to interpret laws. He stressed that "purpose" and "consequences" are especially important.

Breyer used historical examples to show why judges should consider the consequences of their decisions. He mentioned how President Jackson ignored a Court ruling, which led to the Trail of Tears. He also cited the Dred Scott decision, which was a major cause of the American Civil War. Breyer argued that when the Court ignores the effects of its decisions, it can lead to serious problems.

In 2015, Breyer released The Court and the World: American Law and the New Global Realities. This book explored how U.S. law interacts with international law. It discussed how a globalized world affects U.S. court cases.

On March 26, 2024, Breyer released his fourth book, Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, Not Textualism. In an interview, he said that textualism, a philosophy favored by some conservative judges, would not help achieve the goals of those who wrote the Constitution.

Other Views

In a 2010 interview, Breyer said that the Founding Fathers of the United States never intended guns to be completely unregulated. He believed history supported his view in District of Columbia v. Heller, a case about gun rights. He questioned the scope of gun rights, asking if it included "Machine guns? Torpedoes? Handguns?"

Breyer also said he would continue to attend the President's State of the Union Address. He felt it was important for people to see judges as part of the government.

Honors

Breyer was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2004. In 2007, the Boy Scouts of America gave him the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award. In 2018, he became the chairman of the Pritzker Architecture Prize jury.

See also

In Spanish: Stephen Breyer para niños

In Spanish: Stephen Breyer para niños

- Bill Clinton Supreme Court candidates

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 2)

- List of United States federal judges by longevity of service

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Rehnquist Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Roberts Court

- List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |