A. Philip Randolph facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

A. Philip Randolph

|

|

|---|---|

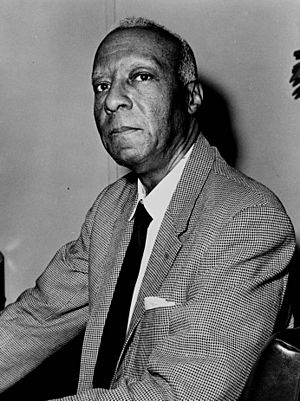

Randolph in 1963

|

|

| Born |

Asa Philip Randolph

April 15, 1889 Crescent City, Florida, U.S.

|

| Died | May 16, 1979 (aged 90) New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Spouse(s) | |

Asa Philip Randolph (born April 15, 1889 – died May 16, 1979) was an important American leader. He worked to improve conditions for workers and for civil rights.

In 1925, he started and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This was the first successful labor union led by African Americans. Randolph was a strong voice in the early Civil Rights Movement and the Labor Movement.

His constant efforts helped lead to big changes. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802. This order stopped discrimination in defense jobs during World War II. Later, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Orders 9980 and 9981 in 1948. These orders promoted fair hiring in the government. They also ended racial segregation in the armed forces.

In 1963, Randolph led the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. At this march, Martin Luther King Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech. Randolph's ideas also inspired the "Freedom Budget." This plan aimed to help with economic problems faced by the Black community.

Contents

Who Was A. Philip Randolph?

Asa Philip Randolph was a key figure in American history. He fought for fairness and equality. He believed that people should work together to make changes.

Early Life and Education

Asa Philip Randolph was born on April 15, 1889. His birthplace was Crescent City, Florida. His father, James William Randolph, was a minister and tailor. His mother, Elizabeth Robinson Randolph, was a skilled seamstress. In 1891, his family moved to Jacksonville, Florida. This city had a strong African-American community.

Randolph learned important lessons from his parents. His father taught him that a person's character was more important than their skin color. His mother taught him the value of education. She also taught him to defend himself and his family if needed.

Asa and his brother, James, were excellent students. They went to the Cookman Institute in East Jacksonville. This was the only high school in Florida for African Americans. Asa loved literature, drama, and public speaking. He was also a star on the school's baseball team. He sang solos with the choir. In 1907, he was the top student in his graduating class.

After school, Randolph worked odd jobs. He spent his time singing, acting, and reading. Reading The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois made him realize the importance of fighting for social equality. Because of discrimination, he could only find manual jobs in the South. So, in 1911, Randolph moved to New York City. There, he continued to work odd jobs. He also took social science classes at City College.

Starting His Career

In 1913, Randolph married Lucille Campbell Green. She was a smart businesswoman and shared his ideas about socialism. She earned enough money to support them both. They did not have any children.

In New York, Randolph learned about socialism. He also learned about the ideas of the Industrial Workers of the World. He met Chandler Owen, a law student. They believed that people could only be truly free if they were not poor. Randolph then developed his unique way of fighting for civil rights. He believed that Black people needed to work together to gain equal rights. He and Owen opened an employment office in Harlem. They helped people from the South find jobs. They also encouraged them to join labor unions.

In 1917, Randolph and Owen started a magazine called The Messenger. It was a bold monthly magazine. It spoke out against lynching. It also opposed the U.S. joining World War I. The magazine encouraged African Americans to fight for an equal society. It also urged them to join unions. The government called The Messenger "the most dangerous of all the Negro publications."

Fighting for Workers' Rights

Randolph's first experience organizing workers was in 1917. He helped create a union for elevator operators in New York City. In 1919, he became president of the National Brotherhood of Workers of America. This union helped Black shipyard and dock workers.

His biggest success was with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). He was elected president in 1925. This union was the first serious effort to organize workers for the Pullman Company. Pullman hired many African Americans as porters. These jobs were good for the time, but porters faced poor working conditions. They were also paid very little.

Under Randolph's leadership, the BSCP quickly gained members. The Pullman Company fought back with violence and firings. In 1928, Randolph planned a strike. But it was called off because Pullman had many replacement workers ready. Union membership then dropped.

Things changed when President Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected in 1932. New laws in 1934 gave porters federal rights. Union membership jumped to over 7,000. After many struggles, the Pullman Company finally agreed to a contract in 1937. Workers gained more pay, shorter workweeks, and overtime pay.

Leading the Civil Rights Movement

Because of his success with the BSCP, Randolph became a leading voice for African-American civil rights. In 1941, he, Bayard Rustin, and A. J. Muste planned a march on Washington. They wanted to protest racial discrimination in war industries. They also wanted to end segregation and get fair access to jobs. Randolph believed in peaceful protests. He was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's success in India. Randolph threatened to have 50,000 Black people march. The march was canceled after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802. This order banned discrimination in war industries. This was a very important early victory for civil rights.

The movement kept growing. In 1942, about 18,000 Black people gathered in New York City. They heard Randolph start a campaign against discrimination. This included discrimination in the military, war industries, government, and unions.

Randolph and other activists kept pushing for rights. In 1947, Randolph and Grant Reynolds worked to end discrimination in the armed services. They formed a group called the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service. When President Truman asked Congress for a draft law, Randolph urged young Black men not to register. Truman needed the support of Black voters. So, on July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman ended racial segregation in the armed forces. He did this through Executive Order 9981.

In 1950, Randolph helped create the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights (LCCR). This group has been a major civil rights organization. It helped pass every major civil rights law since 1957.

Randolph also worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr.. In 1957, schools in the South resisted integration. Randolph organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom with King. In 1958 and 1959, Randolph organized Youth Marches for Integrated Schools in Washington, D.C. He also helped Rustin teach King how to organize peaceful protests. These protests in cities like Birmingham and Montgomery led to violent reactions from police. These events were shown on television around the world. This helped the Kennedy administration create new civil rights laws.

Randolph finally saw his dream of a March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom come true. On August 28, 1963, between 200,000 and 300,000 people gathered in Washington, D.C. This rally is seen as a high point of the Civil Rights Movement. It helped keep the issue in the public eye. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed the next year. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed. Randolph's contributions to the Civil Rights Movement were very important.

His Beliefs and Later Life

Randolph did not often speak publicly about his religious beliefs. He wanted to avoid upsetting people from different backgrounds. He was raised in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He was one of the first to use prayer protests. These became a key tactic in the civil rights movement.

Randolph died in his apartment in Manhattan on May 16, 1979. He had heart problems and high blood pressure for several years. He had no living relatives. His wife, Lucille, had passed away in 1963.

Awards and Recognition

- In 1942, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People gave Randolph the Spingarn Medal.

- In 1953, the Black Elks gave him their Elijah P. Lovejoy Medal. This award is for Americans who work to advance human rights.

- On September 14, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson gave Randolph the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- In 1967, he received the Eugene V. Debs Award.

- In 1967, he received the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award. This award is named after a letter from Pope John XXIII about peace among nations.

- He was named Humanist of the Year in 1970 by the American Humanist Association.

- In January 2014, he was named to the Florida Civil Rights Hall of Fame.

How He Is Remembered

Randolph had a big impact on the Civil Rights Movement. The Montgomery Bus Boycott was led by E. D. Nixon. Nixon was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. He was influenced by Randolph's nonviolent methods. Across the country, the Civil Rights Movement used tactics Randolph pioneered. These included encouraging African Americans to vote together. They also included mass voter registration and training for nonviolent direct action.

Places Named After Him

- Amtrak named one of their best sleeping cars, the "A. Philip Randolph."

- The A. Philip Randolph Academies of Technology in Jacksonville, Florida, is named in his honor.

- A. Philip Randolph Boulevard in Jacksonville, Florida, was renamed in his honor in 1995.

- A. Philip Randolph Heritage Park is in Jacksonville, Florida.

- A. Philip Randolph Campus High School in New York City is named after him.

- Randolph Technical High School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was named in his honor.

- The A. Philip Randolph Career and Technician Center in Detroit, Michigan, is named in his honor.

- The A. Philip Randolph Institute is named after him.

- PS 76 A. Philip Randolph in New York City is named in his honor.

- The A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum is in Chicago.

- Edward Waters College in Jacksonville, Florida, has an exhibit about A. Philip Randolph.

- Randolph Street in Crescent City, Florida, was dedicated to him.

- The A. Philip Randolph Library is at Borough of Manhattan Community College.

- A. Philip Randolph Square park in Central Harlem was renamed to honor him in 1964.

In Books and Movies

- In 2015, the book The Road to Character by David Brooks included him.

- In 1994, a PBS documentary called A. Philip Randolph: For Jobs and Freedom was made.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed A. Philip Randolph in his 100 Greatest African Americans.

- The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was made into a 2002 film. It was called 10,000 Black Men Named George. Andre Braugher played A. Philip Randolph. The title refers to how Pullman porters were often called "George."

Other Ways He Is Honored

- A statue of A. Philip Randolph is in Union Station in Washington, D.C.

- A bronze statue of Randolph is in Boston's Back Bay station.

- James Farmer, who helped start the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), said Randolph was a main influence.

- Randolph was added to the Labor Hall of Honor in 1989.

See Also

In Spanish: A. Philip Randolph para niños

In Spanish: A. Philip Randolph para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |