Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters facts for kids

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) was a very important labor union. It was started in 1925. The BSCP was the first union led by African Americans to be officially recognized by the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

This union brought together about 18,000 railway workers. These workers were from Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Many of them were Pullman porters. Being a Pullman porter was a key job for Black Americans after the American Civil War.

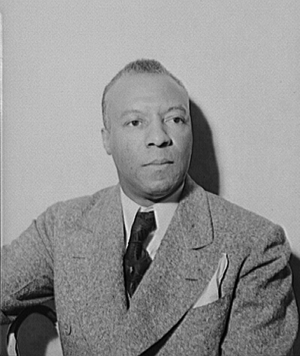

The BSCP leaders became important figures in the Civil Rights Movement. People like A. Philip Randolph, Milton P. Webster, and C. L. Dellums fought for fair jobs. They also worked to end segregation in the Southern United States. Some members, like E. D. Nixon, even led local civil rights efforts.

In the 1960s, fewer people traveled by train. This caused the union's membership to shrink. In 1978, the BSCP joined with another union. It became part of the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC). Today, this union is called the Transportation Communications International Union.

Contents

Working for the Pullman Company

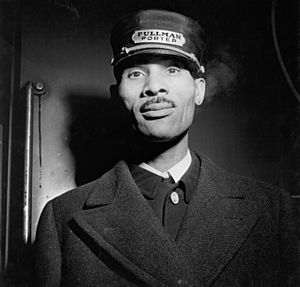

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Pullman Company was a huge employer of Black people. The company tried to look good by supporting Black churches and newspapers. It also paid some porters well. This allowed them to live a middle-class life in their communities.

However, working for Pullman was not as good as it seemed. Porters relied on tips for most of their pay. White passengers often called all porters "George." This was the first name of George Pullman, the company's founder. Porters had to travel 11,000 miles a month to earn their basic wage. This was almost 400 hours of work.

In 1934, porters worked over 73 hours a week on average. They earned only 27.8 cents an hour. Other factory workers averaged under 37 hours a week. They earned 54.8 cents per hour. Porters also spent about 10% of their time doing unpaid setup and cleanup. They had to pay for their own food, lodging, and uniforms. These costs could take up half their wages. They were even charged if a passenger stole a towel! Porters could not become conductors. This job was only for white workers.

The company tried to stop any union efforts. They would fire or isolate union leaders. Pullman also used spies to watch employees. Sometimes, company agents even attacked union organizers.

On August 25, 1925, 500 porters met in Harlem. They decided to try organizing again. They secretly started their union campaign. They chose Randolph to lead because he didn't work for Pullman. This meant the company couldn't fire him. The union's motto showed their anger: "Fight or Be Slaves."

Forming the Union

The AFL union claimed to support equal rights. But it often discriminated against Black workers. Racism was common in many US institutions. This made it hard for white labor unions to accept Black workers.

In the 1920s, some parts of the AFL started to change. Groups like the Urban League and the Socialist Party of America began focusing on Black workers' rights. Randolph himself was a member of the Socialist Party. From the start, the BSCP fought for Black workers to join the organized labor movement. They faced strong opposition and racism. As BSCP co-founder Milton P. Webster said, "any time we have an American institution composed of white people there is prejudice in it."

Before 1925, the Pullman Company had crushed many attempts by porters to form a union. In 1925, union organizer Ashley Totten invited Randolph to speak. Randolph showed he understood the problems of Black workers. He also saw the need for a real union. So, he was asked to lead the effort. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters officially began on August 25, 1925.

A key to the union's success was getting many members. They focused on three large Pullman terminals: Chicago, Oakland, and St. Louis. In Chicago, the main person was Milton Price Webster. He was the son of formerly enslaved parents. Webster had been a Pullman Porter for 20 years. The company fired him for trying to organize porters before.

Webster was a strong leader. He was well-known in Chicago politics. He wasn't a great speaker like Randolph. But he was smart and committed to helping working people. He could command an audience with his knowledge and sharp mind.

Webster was unsure about Randolph's socialist ideas. But he listened to fellow organizer John C. Mills. Webster then set up meetings for Randolph and Chicago porters. They met every night for two weeks. After hearing Randolph speak, Webster agreed he was the right person to lead the new union. Webster would open the meetings, and Randolph would close them. This helped launch the Chicago division of the Brotherhood.

The Pullman Company fought back. They said the new union was an outside group with foreign ideas. They got support from ministers and Black newspapers they had helped. The company also created its own union. This was called the Employee Representation Plan. Local officials, like E.H. Crump in Memphis, also helped the company. They would stop or ban BSCP meetings.

For years, the union kept fighting Pullman. They also fought other groups that were against them. The BSCP even asked the government for help. In 1927, they asked the Interstate Commerce Commission to investigate Pullman's practices. But the ICC said it didn't have the power to do so.

By 1928, the union had organized about half of the porters. But they still weren't recognized by the company. BSCP leaders decided a strike was the only way. Some leaders wanted to strike to show strength. Randolph was more careful. He hoped the threat of a strike would make the government step in. He wanted the National Mediation Board (NMB) to bring Pullman to the negotiating table.

The NMB secretly met with Pullman. They refused to help the BSCP. They said the union wasn't strong enough to stop Pullman's service. Even though the union voted to strike, Pullman convinced the NMB that the union couldn't do it. In July 1928, Randolph called off the strike just hours before it was to begin. The leaders knew a strike then would have badly hurt the union. They agreed the union wasn't strong enough yet.

This caused problems for the union. The Great Depression also made things worse. The union had little money. Pullman continued to punish porters. Membership dropped sharply. The union might have disappeared. But dedicated leaders like Randolph, Webster, and others kept it going.

Randolph and Webster worked closely together. They shared a strong commitment to organizing Black workers. They wanted to improve working conditions and the lives of Black workers and their families.

In 1929, the AFL gave official status to individual BSCP chapters. These were in cities like Chicago, New York City, and St. Louis.

By 1933, BSCP membership was very low, only 658. The union headquarters even lost phone and electricity. But in 1934, the Roosevelt administration changed a law. The next year, the Wagner-Connery Act was passed. This law made company unions illegal. It also covered porters. The BSCP immediately asked the NMB to recognize them. The BSCP won the election against the company union. On June 1, 1935, they were officially certified.

Negotiations with the Pullman Company began. But they kept getting stuck. The BSCP asked the NMB for help again in April 1937. Pullman was still using spies to watch union meetings.

Finally, a contract was signed on August 25, 1937. It started in October 1937. This contract raised wages for porters and maids. It set a basic 240-hour month. It also gave time-and-a-half pay for overtime after 260 hours. Pullman said the wage increases would cost them about $1.5 million a year. The company also agreed to pay for porters' uniforms after 10 years of work.

The Role of Women

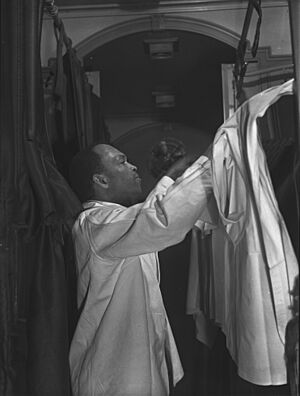

The BSCP was created for all Pullman workers, including maids. Many maids were educated Black or Chinese-American women. But they were called "unskilled service workers." They had to clean berths, care for sick passengers, and even give free manicures.

Six weeks after the BSCP started, female Pullman employees and union members' relatives formed groups. These were called the Women's Economic Councils. In 1938, they became the International Ladies' Auxiliary to the BSCP (ILA). Many of these women had worked in New York's clothing industry. They had experience in union work from the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.

The ILA focused on raising money and sharing information about the union. Maids were often fired for their union activities.

Individual women also made a big difference. When her husband was fired for his union work, Rosina Tucker demanded he be rehired. She later helped start the ILA. She also recruited for the BSCP and became a civil rights activist. Halena Wilson, president of the Chicago ILA, fought for fair wages and against poll taxes. Frances Mary Albrier organized Pullman maids in the 1920s. She said their job was to "educate the black public and black women" about the union.

Growth in Canada

From 1917 to 1939, working conditions on Canadian railways were not good. Porters working for the Canadian National Railways (CNR) started to demand better rights.

In 1942, the union expanded into Canadian cities. These included Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. Later, Calgary, Edmonton, and Vancouver also joined. Canadian workers were very excited to join the BSCP. Just three years after expanding, the BSCP brought big changes. They improved wages and working standards for Canadian railway workers.

Civil Rights Leadership

The BSCP got its official charter from the AFL in 1935. This was the same year the NMB recognized it. Before this, the AFL only recognized individual BSCP chapters. This was not ideal. But it allowed Randolph to attend AFL meetings. There, he pushed for Black workers to be organized equally with white workers. Randolph kept the BSCP in the AFL.

Randolph became a leader of the most important Black labor group in the US. He was chosen to lead the National Negro Congress in 1937. This group brought together many major Black civil rights organizations. Randolph later left the NNC due to disagreements. But his importance continued to grow.

In 1941, Randolph threatened a march on Washington. He had support from the NAACP and other leaders. This forced the government to act. President Roosevelt banned discrimination by defense companies. He also set up the Fair Employment Practices Committee (FEPC). This committee enforced the ban. Milton Webster worked to make the FEPC effective. Randolph also pushed for an end to segregation in the military. President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981 banning it seven years later.

BSCP members played a big role in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1940s and 1950s. E. D. Nixon was a BSCP member. He was a strong voice for Black rights in Montgomery. Nixon used his organizing experience and freedom from local economic pressure. BSCP members also helped share information and connect communities. They brought news and political ideas from the North back to their hometowns.

Randolph helped bring the CIO back into the AFL in 1955. By then, Randolph was seen as a wise elder statesman in the civil rights movement. Even as the railroad industry changed, he remained important.

Randolph and his helper, Bayard Rustin, were key organizers of the 1963 March on Washington. Randolph spoke at the march, saying: "Let the nation know the meaning of our numbers. We are not a pressure group. We are not an organization. We are not a mob. We are the advance guard of a massive moral revolution that is not confined to the Negro, nor is it confined to civil rights, for our white allies know that they are not free while we are not."

In 1953, Violet King Henry became the first Black woman lawyer in Canada. The union's president and vice-president traveled to Alberta to honor her.

Joining with BRAC

Passenger train travel dropped a lot after the 1940s. At its peak, the BSCP had 15,000 members. By the 1960s, only 3,000 porters had regular routes. Milton Webster was supposed to take over as president after Randolph retired. But Webster died in 1965 from a heart attack. C. L. Dellums replaced Randolph as president in 1968.

The BSCP merged with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC) ten years later. Dellums' successor, Leroy J. Shackelford, became president of BRAC's Sleeping Car Porters Division. In 1984, this division joined with Amtrak clerical employees. They formed a new Amtrak Division with about 5,000 members. This was the largest organized labor group on the Amtrak system.

When Mr. Shackelford retired in 1985, his position was not filled. Michael J. Young became the general chairman of the BRAC Amtrak Division. He was the first non-African American to lead the on-board group.

Three unions representing Amtrak on-board workers joined together. These were BRAC, the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees (HERE), and the Transport Workers Union (TWU). They formed the Amtrak Service Workers Council (ASWC). They removed old job divisions and seniority lists. Now, one agreement covers all on-board workers. The ASWC leadership rotates each year among the heads of the member unions.

Stage and Film

In 1982, a documentary called Miles of Smiles, Years of Struggle won awards. A book with the same name was later written based on the film.

The story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was made into a movie in 2002. It was called 10,000 Black Men Named George. Robert Townsend directed it. Andre Braugher played A. Philip Randolph.

The play Pullman Porter Blues (2012) by Cheryl West tells a story. It shows a night on the Panama Limited train. It explores the challenges and tensions among three generations of Pullman Porters.

The Porter (2022) is an 8-part TV show. It was made by CBC and BET. It is a fictional story partly inspired by the creation of the BSCP.

Notable Pullman Porters

- Big Bill Broonzy

- Matthew Henson

- Claude McKay

- Benjamin Mays

- Oscar Micheaux

- E. D. Nixon

- Gordon Parks

- Simon Haley

- Cecil Newman