Pullman porter facts for kids

Pullman porters were men who worked on trains as attendants in sleeping cars. After the American Civil War, a man named George Pullman started hiring former slaves for these jobs. Their main tasks included carrying luggage, shining shoes, preparing beds for passengers, and serving food and drinks.

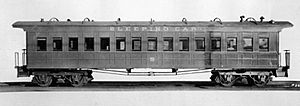

Pullman porters worked on American railroads from the late 1860s until the Pullman Company stopped operating in 1968. Some porters continued working for other railroad companies and later for Amtrak. The term "porter" is now often replaced with "sleeping car attendant."

Until the 1960s, almost all Pullman porters were Black men. They played a big part in helping to create the Black middle class in America. In 1925, led by A. Philip Randolph, they formed the first all-Black union, called the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This union was very important for the Civil Rights Movement.

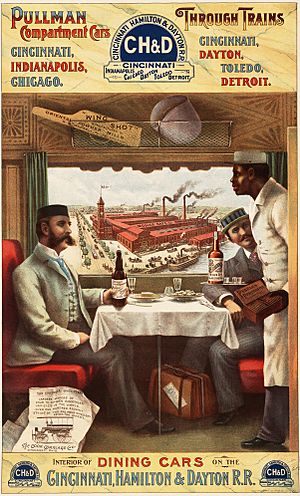

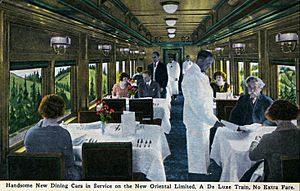

Besides sleeping cars, the Pullman Company also provided parlor cars (for relaxing) and dining cars. These dining cars had Black cooks and waiters. Pullman also hired Black maids for special deluxe trains. These maids helped women passengers, especially those with children. They would assist with bathing, do manicures, sew clothes, and help with kids.

Contents

The History of Pullman Porters

Before the 1860s, sleeping cars on trains were not very common. George Pullman was a pioneer in creating comfortable sleeping spaces on trains. By the late 1860s, he decided to hire only African-American men as porters. After the Civil War ended in 1865, Pullman knew there were many former slaves looking for work.

He also understood that most Americans did not have personal servants at home. But wealthy people were used to being served by butlers. Pullman wanted to offer a fancy, upper-class experience to his passengers. So, having uniformed porters made traveling on his sleeping cars feel special.

From the beginning, porters were shown in Pullman's advertisements. They made his cars stand out from others. Soon, most other train companies also started hiring African-Americans as porters, cooks, waiters, and station porters (Red Caps).

The Pullman Company was a separate business from the railroad lines. It owned and ran the sleeping cars that were attached to most long-distance passenger trains. You could think of Pullman as a chain of "hotels on wheels." Porters were there to prepare beds, serve food, send telegrams, shine shoes, and help with other needs.

Even though the pay was low for the time, being a Pullman porter was one of the best jobs available for Black men. This was especially true during a time when there was a lot of racial prejudice. However, it also meant being seen as a servant and sometimes facing disrespect.

Many passengers would call every porter "George." This was a common practice in the South where slaves were sometimes named after their owners. Other men named George did not like this. They even started a group called the "Society for the Prevention of Calling Sleeping Car Porters George."

In 1926, this group convinced the Pullman Company to put small cards in each car showing the porter's real name. Out of 12,000 porters and waiters, only 362 were actually named George.

Porters did not earn enough money from their wages alone. They had to rely on tips to make a living. Walter Biggs, whose father was a Pullman porter, shared stories about famous passengers. He said that porters loved working on trains with actor Jackie Gleason. Gleason would give every porter $100 and treat them with respect. He would call them by their first names, not "George."

The number of porters working on trains decreased in the 1960s. This happened because fewer people were taking long-distance trains. More people started traveling by car or airplane. By 1969, there were only 325 Pullman porters left. Their average age was 63.

What Porters Did and How They Were Paid

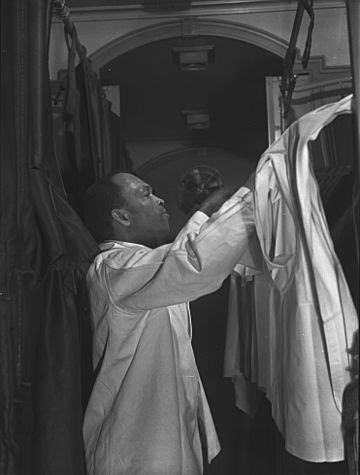

A porter's job involved many tasks. They greeted passengers, carried their bags, and made up the sleeping beds. They also served food and drinks from the dining car, shined shoes, and kept the cars clean. Porters had to be available day and night to help passengers. They were always expected to smile, which led them to jokingly call their job "miles of smiles."

According to historian Greg LeRoy, a Pullman porter was like a "hotel maid and bellhop" on a moving hotel. The Pullman Company saw porters as just another piece of equipment, like a light switch. Porters worked very long hours, sometimes up to 20 hours at a time. They often had to arrive at work hours early to prepare their car without pay. They were even charged if a passenger stole a towel or a water pitcher. On overnight trips, they only got three to four hours of sleep, and this time was taken out of their pay.

In 1926, a report by the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters showed that a regular porter's minimum monthly wage was $72.50. With tips, they averaged about $58.15 more. However, porters had to pay for their own meals, lodging, uniforms, and shoe-shine supplies. These costs added up to about $33.82 a month.

Porters only got overtime pay if they worked more than 11,000 miles or about 400 hours a month. Maids earned a minimum of $70 a month and received fewer tips. In comparison, Pullman conductors, who had their own union, earned at least $150 a month for 240 hours of work.

The company offered a health and life insurance plan for $28 a year. They also paid a pension of $18 a month to porters who reached age 70 and had worked for at least 20 years. In 1925, the Pullman Company made over $19 million in profit and paid out over $10 million to its stockholders.

Lyn Hughes, who founded the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, explained that porters did not earn a living wage from their salary. They depended on tips. The company also made them pay for their own uniforms and shoe polish. There was little job security, and inspectors would often suspend porters for small reasons.

How Porters Were Seen

Larry Tye, who wrote a book about Pullman porters, said that George Pullman knew that former slaves had been trained to take care of every customer's wish. Tye also explained that Pullman knew travelers would not be embarrassed if they ran into a porter later. Porters would not remember anything private that happened during the trip.

Thomas Fleming, a Black historian and journalist, worked as a bellhop and then a cook for a railroad. He wrote about the mixed feelings of being a Pullman porter. He said that the job was one of the best a Black man could get in America. Porters were in charge of their sleeping cars. But their job also meant being a servant. They had the best job in their community but sometimes felt like they had the worst job on the train. They could be trusted with white passengers' children and safety, but only for the trip.

In 2008, Amtrak learned about The Pullman Porters National Historic Registry. This was a five-year project by Dr. Lyn Hughes for the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum. Amtrak worked with the museum to find and honor surviving porters. They found a few porters who were in their 90s or over 100 years old. The project coordinator noted that even at that age, the men were very elegant and always wore suits and ties.

Forming a Union

The Order of Sleeping Car Conductors was formed in 1918. Only white men could join this group. Because Black men were not allowed, A. Philip Randolph started organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. With the motto "Fight or Be Slaves," 500 porters met in Harlem in 1925. They decided to form a union. Under Randolph's leadership, this first Black union was created. Slowly, working conditions and salaries for porters got better.

By forming the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, these porters also helped set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement, which began in the 1950s. E. D. Nixon, a union organizer and former Pullman porter, played a key role in organizing the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama in 1955. He was the one who bailed Rosa Parks out of jail and chose her to be the symbol for the boycott.

By the 1960s, passenger rail travel declined. The contribution of Pullman porters became less known. For some in the African-American community, the job became a symbol of serving white people.

The Pullman Company closed down in 1969. Railroads no longer hired only Black men as porters. In 1978, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters joined with a larger union called the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks.

Helping Create the Black Middle Class

The Black community looked up to Pullman porters. Many people believe they greatly helped create America's Black middle class. Timuel Black, a Black historian, said in 2013 that porters were "good looking, clean and immaculate in their dress." He added that they were good role models for young men. Being a Pullman porter was a respected job because it offered a steady income and a chance to travel across the country. This was rare for Black people at that time.

In the late 1800s, Pullman porters were among the only people in their communities who traveled widely. Because of this, they brought new information and ideas from the outside world back to their communities. Many porters supported community projects, like schools. They saved money carefully to make sure their children could get an education and better jobs.

Important figures like Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown had Pullman porters in their families. Marshall himself was also a porter, as were Malcolm X and the photographer Gordon Parks.

A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum

In 1995, Lyn Hughes started the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum. It celebrates the life of A. Philip Randolph and the important role of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. It also honors other African-Americans in the U.S. labor movement. The museum is in Chicago. It is located in one of the original houses built by George Pullman for his workers. It is part of a special historic district. The museum has many items and documents related to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. In 2001, the museum also began creating a list of Black railroad employees who worked from the late 1800s to 1969.

Honoring Their Legacy

In 2008, Amtrak and the A. Philip Randolph Museum honored Pullman porters in Chicago. Lyn Hughes, the museum founder, said it was important for Amtrak to honor those who helped shape its own history. She also noted that it completed the effort to create the Pullman Porter Registry.

In 2009, during Black History Month, Amtrak honored Pullman porters in Oakland, California. An AARP journalist wrote that porters were "dignified men who did undignified labor." They made beds, cleaned toilets, shined shoes, and cooked meals in small, moving spaces. Amtrak invited five retired members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to speak. Lee Gibson, who was 98, said his train ride to the event was nice. He added, "I got the service I used to give." He remembered his years as a porter fondly, calling it "a wonderful life."

In 2009, Philadelphia honored about 20 former Pullman employees who were still alive. Frank Rollins, a 93-year-old former cook and porter, spoke to NPR. He said the railway wanted "Southern boys" to work in dining cars. They thought these men had a certain personality that Southern passengers liked. Rollins also spoke about the racist comments Black men faced. But he also shared positive experiences. He recalled a speech he would give: "My name is Frank Rollins. If you can't remember that, that's OK. You can call me porter—it's right here on the cap, you can be able to remember that. Just don't call me 'boy' and don't call me George."

In August 2013, the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum celebrated the 50-year anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. This was a very large political gathering for human rights in U.S. history. Lyn Hughes said that many people in Chicago might want to celebrate the march's anniversary in their own community. She also noted that many people do not know that Asa Philip Randolph was the first activist who inspired the March on Washington. The museum planned speakers and films about Black labor history. Two former Pullman porters, Milton Jones (age 98) and Benjamin Gaines (age 90), were expected to attend.

Notable Pullman Porters

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |