Benjamin Mays facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benjamin Mays

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 6th President of Morehouse College | |

| In office August 1, 1940 – July 1, 1967 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles D. Hubert As Acting President |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Gloster |

| 1st Dean of the School of Religion at Howard University |

|

| In office January 1, 1934 – January 3, 1940 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | John Moore |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Benjamin Elijah Mays

August 1, 1894 Ninety Six, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 1984 (aged 89) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Dr. Benjamin E. Mays Memorial Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

Ellen Harvin

(m. 1920–1923)Sadie Gray

(m. 1926–1969) |

| Parents | Louvenia Carter Mays Hezekiah Mays |

| Alma mater | Virginia Union University Bates College University of Chicago |

| Known for | Civil rights activism |

| Nicknames | "Bennie"; "Buck Bennie" |

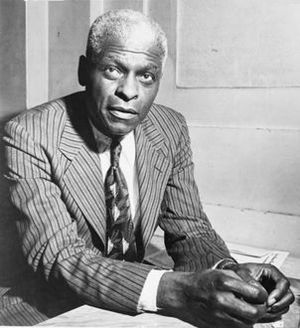

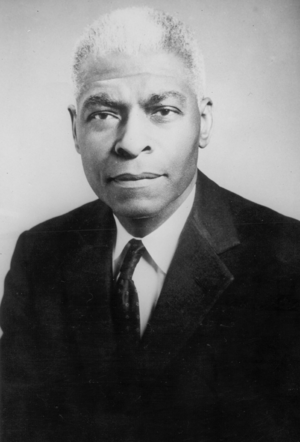

Benjamin Elijah Mays (August 1, 1894 – March 28, 1984) was an important American leader. He was a Baptist minister and a key figure in the civil rights movement. Many believe he helped create the main ideas for the movement.

Mays taught and guided many famous activists. These included Martin Luther King Jr., Julian Bond, Maynard Jackson, and Donn Clendenon. He believed strongly in Black people having control over their own lives. Mays learned about social justice and peaceful protest from his family when he was young. His biggest impact was during his nearly 30 years as the sixth president of Morehouse College. This is a historically Black university in Atlanta, Georgia.

Mays was born in the Jim Crow South. This was a time when laws kept Black and white people separate. His parents were sharecroppers, meaning they farmed land owned by others. He went North to study at Bates College and the University of Chicago. He started his work as a pastor in Georgia. Later, he became the first Dean of the School of Religion at Howard University in 1934. This made him well-known as a supporter of the New Negro movement.

Six years later, Mays was chosen to lead Morehouse College. The college was having money problems. During his time from 1940 to 1967, the college's money doubled. The number of students grew four times larger. Morehouse also became a top academic school. By the 1960s, Mays made Morehouse a place that produced many "African-American firsts" in the U.S.

Morehouse College had a small number of students. This allowed Mays to personally guide many of them. His most famous student was Martin Luther King Jr. They first met in 1944. King called Mays his "intellectual father." Mays called King his "spiritual son." After King's "I Have A Dream" speech in 1963, Mays gave the closing prayer. Five years later, after King was killed, Mays gave the speech at his funeral. He spoke about King in his famous "#No Man is Ahead of His Time" speech.

Mays left the Morehouse presidency in 1967. He continued to be a leader in the African American community. He traveled and gave speeches. From 1969 to 1978, he led the Atlanta Board of Education. There, he started the desegregation of schools in Atlanta.

Mays is often called the "movement's intellectual conscience." Historian Lawrence Carter said Mays was "one of the most significant figures in American history." Many places honor him. These include streets, buildings, statues, awards, and scholarships. People have also tried to get him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is a very high award. Since 1995, Mays and his wife, Sadie Gray, have been buried on the campus of Morehouse College.

Early Life and Education

Growing Up in South Carolina

Benjamin Elijah Mays was born on August 1, 1894. He was the youngest of eight children. His parents, Louvenia Carter Mays and Hezekiah Mays, were born into slavery. They were freed later in their lives. Mays' father worked as a sharecropper to earn money.

Mays was taught to be careful around white people. He was also taught to be proud of being Black. His older sister, Susie, taught him to read before he started school. This gave him a head start. Teachers said he was "destined for greatness." He was inspired by leaders like Fredrick Douglass and Booker T. Washington. The Bible was also important to him. During this time, Benjamin Tillman gained power in South Carolina. This led to more lynching and segregation in Mays' area.

Starting His Education

In 1911, Mays went to the Brick House School. It was a school supported by Baptists. He then moved to the high school at South Carolina State College. He graduated in 1916 at age 22. He was the best student in his class. Teachers often let Mays teach math to other students. He won awards for debate and math. A teacher told him to go to the University of Chicago for graduate school.

Before graduate school, Mays needed a college degree. His family wanted him to go to a Baptist university. So, he went to Virginia Union University. He did not like the violence against Black people in Virginia. His advisors told him to look at schools in the North. They were seen as better than Southern schools.

Four professors at Virginia Union had gone to Bates College in Maine. They told Mays to apply. Bates had very high standards. Mays worked hard to improve his grades. He wrote to Bates president George Colby Chase. Chase gave him a full scholarship. Mays' old president warned him that Bates would be "too hard for a colored boy." But Mays ignored him and enrolled in 1917. He was 23 years old.

At Bates, Mays felt pressure to do as well as the "Yankees." He studied Greek, math, and speech. He experienced little racism at college. But he was scared when he saw a movie where the crowd cheered for a white slave owner. Mays was captain of the debate team. He also played football. He graduated with honors in 1920.

His Marriages

After college, Mays married Ellen Edith Harvin in August 1920. They had met in South Carolina. She was a home economics teacher. She died after a short illness two years later. She was 28.

He met his second wife, Sadie Gray, at South Carolina State College. They married on August 9, 1926. Mays kept his relationship with Sadie private. He burned most of their letters.

Early Career and Studies

Graduate School and Early Work

On January 3, 1921, Mays started graduate school at the University of Chicago. He earned his master's degree in 1925. Early in his career, he joined Omega Psi Phi. This was a fraternity for Black men. Mays saw it as a way to connect with other smart people.

To pay for school, Mays worked as a Pullman Porter. This was a railway assistant. He tried to organize other porters to get better pay. He was fired for "attracting too much attention to labor rights." His time at the University of Chicago was marked by segregation. He had to sit in "colored" areas in dining halls. He could only use certain rooms for reading. Mays accepted this because he wanted his degree.

He became a Baptist minister in 1921. From 1921 to 1923, he was a pastor at Shiloh Baptist Church in Atlanta. After getting his master's degree, he taught English at South Carolina State College. He left this job because he disagreed with other teachers about school standards.

In 1926, he moved to Tampa, Florida. He became the director of the Tampa Urban League. He helped write a report about the challenges faced by African-American communities in Tampa. He is honored with a bust on the Tampa Riverwalk. From 1928 to 1930, he worked for the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA).

In 1932, Mays returned to the University of Chicago. He wanted to get his Ph.D. He decided to study religion. In 1933, he wrote his first book, The Negro's Church. It was the first study of the black church in the U.S. He earned his Ph.D. in 1935.

Leading at Howard University

After getting his Ph.D., Mays became the dean of religious studies at Howard University in Washington. He was asked to build up the department. First, he improved the library. He also got money from the government and rich donors. This helped the university grow a lot. Salaries for professors increased. New dorms and lecture halls were built.

In 1938, he published his second book. In 1939, his School of Religion was recognized by a national group. Mays became known for having high standards. He spoke out against the idea that Black men were naturally more violent. He strongly supported the New Negro movement.

In January 1940, Mays was asked if he wanted to be president of Morehouse College. The college was struggling financially. Mays was interested. On March 10, 1940, he was offered the job. When Mays left Howard University, a new building was named "Benjamin Mays Hall" in his honor.

Meeting Mahatma Gandhi

In 1936–37, Mays traveled to India. He met Mahatma Gandhi. They talked for an hour and a half. They discussed the power of peaceful protest. This meeting helped shape Mays' ideas about civil rights. Gandhi told Mays that violence was never acceptable. He said, "one must pay the price for protest, even with one's life."

Leading Morehouse College (1940–1967)

Early Years as President

Mays became the sixth president of Morehouse College on August 1, 1940. The school was in serious financial trouble. In his first speech, he said, "If Morehouse is to continue to be great; it must continue to produce outstanding personalities." Mays wanted to improve student training. He also wanted to increase enrollment and grow the college's money.

Many people at the college called him a "builder of men." He wanted to improve the curriculum. He especially wanted to train more Black doctors, ministers, and lawyers. Morehouse was a school that prepared students for these fields.

Improving Finances

When Mays started, the college had many unpaid student bills. This threatened the college's money. In 1933, Morehouse was doing so badly that another university had taken over its finances. Mays became known for being careful with money. He demanded tuition payments on time. Students sometimes called him "Buck Bennie."

However, he often helped students pay their bills. He would offer them work on campus. Within two years, Mays was so successful that he regained control of Morehouse's money.

World War II's Impact

Soon after Mays made progress, World War II began. Many students were drafted for military service. The head of the college's board wanted to close the school during the war. Mays strongly disagreed. He suggested opening the school to younger students who could not be drafted. He also worked to improve the quality of students. He made admissions harder and changed the academic plan.

Growing Recognition

Mays was a tall man who carried himself with dignity. His strong presence matched his great intelligence. When he entered a room, people noticed him.

He received honorary degrees from Bates College in 1947 and the University of Chicago in 1949. Even though he was a college president, he could not vote until he was 52 years old. In 1954, a magazine called Pulpit named him one of the top 20 preachers in America. Another Black magazine called him one of the "Top Ten Most Powerful Negros" in the nation.

Jackie Robinson's Visit

In 1966, Mays was invited to an Atlanta Braves baseball game. Jackie Robinson invited him as a guest of honor. The team had just moved to Atlanta. Robinson invited Mays because of his work to help integrate the baseball team. Robinson said Mays made things easier for Black baseball players.

Advising U.S. Presidents

As president, Mays was a popular speaker. He met many national and international leaders. He was a trusted advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter. President Truman appointed him to a conference on children and youth. When Pope John XXIII died in 1963, President Kennedy sent Mays to represent the U.S. at the funeral in Rome, Italy.

During the Kennedy years, some senators blocked Mays from joining the United States Commission on Civil Rights. They accused him of being a Communist, but Mays denied it. His relationship with President Jimmy Carter was very good. Carter visited Mays' home. Mays campaigned for Carter in his presidential runs. Carter often wrote to Mays, asking for his advice on human rights and discrimination.

Morehouse's Growth Under Mays

Mays wanted to hire more teachers and pay them better. To do this, he was strict about collecting student fees. He also wanted to increase Morehouse's money. By the end of his 27 years, he had more than quadrupled the college's money. Student enrollment also grew by 169%. More students were encouraged to go on to graduate school.

Connection to Martin Luther King Jr.

Mays first met Martin Luther King Jr. when King was a student at Morehouse College. From 1944 to 1948, King often went to the college chapel to hear Mays preach. After sermons, King would talk to Mays about his ideas. He would even follow Mays to his office.

Mays was also a friend of King's father, Martin Luther King Sr.. Mays often ate at the King family's home. He talked with young Martin Luther King Jr. about his future. King's mother, Alberta Williams King, said Mays was a "great influence on Martin Luther King Jr." She called him "an example of what kind of minister Martin could become."

As King faced challenges in the civil rights movement, Mays supported him. Mays was King's advisor for 14 years. He helped King deal with threats and public battles.

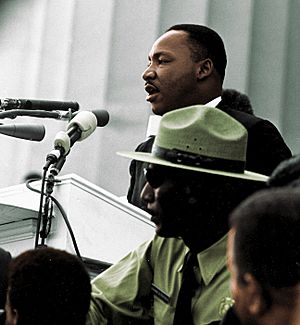

After King became famous from the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, he called Mays his "spiritual and intellectual mentor." Mays called King his "spiritual son." Mays gave the closing prayer at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. This is where King gave his famous ""I Have a Dream" speech."

"No Man is Ahead of His Time" Speech

Mays and King had a close bond. They promised each other that whoever lived longer would give the eulogy at the other's funeral.

On April 9, 1968, Mays gave a eulogy for King. It became known as the "No Man is Ahead of His Time" speech. He spoke to about 150,000 mourners. He said:

If Jesus was called to preach the Gospel to the poor, Martin Luther was called to give dignity to the common man. If a prophet is one who interprets in clear and intelligible language the will of God, Martin Luther King Jr. fits that designation. If a prophet is one who does not seek popular causes to espouse, but rather the causes he thinks are right, Martin Luther qualified on that score.

No! He was not ahead of his time. No man is ahead of his time. Every man is within his star, each in his time. Each man must respond to the call of God in his lifetime and not in somebody else's time. Jesus had to respond to the call of God in the first century A.D., and not in the 20th century. He had but one life to live. He couldn't wait.

The speech was very well received. It was later called "a masterpiece of twentieth century oratory." After King's death, Mays urged people not to riot. He said they should turn their sorrow into hope for the future. He wanted them to use their anger to work peacefully for change.

After Morehouse (1967–1981)

Social Tours and Advocacy

After leaving Morehouse, Mays taught again. He also advised the president of Michigan State University. He published a book of his sermons called Disturbed About Man. This book described his early life and the racial challenges he faced. He began giving speeches at colleges and schools. He wanted to spread messages of religious and racial tolerance. He gave 250 speeches before stopping in the early 1980s.

In 1978, the U.S. Department of Education gave him an award. The South Carolina State House also hung a portrait of him. Mays deeply appreciated these honors from his home state. He had left South Carolina fearing for his life. During the 1970s, Mays became known as a "native son" in his birthplace.

Leading the Atlanta School Board

At age 75, Mays was elected president of the Atlanta Public Schools Board of Education. He oversaw the peaceful desegregation of Atlanta's public schools. This happened because of a federal court order in 1970. Some board members argued against creating bus routes for desegregation. But Mays insisted, citing a Supreme Court decision.

Mays ordered the city to create bus routes for African-American neighborhoods. The board did not fully support this. So, Mays worked with the city government to create the Atlanta Compromise Plan.

Mays' "commanding and demanding personality" helped greatly with desegregation in Atlanta. The plan aimed for "colorless" administration. This meant Black and white students rode the same buses. This was called the "Majority to Minority" (M to M) volunteer plan. It allowed students to transfer to schools where their race was in the minority. This helped Black students in Atlanta. The program was later called the "Volunteer Transfer Program" (VTP). On July 28, 1974, Mays signed the order declaring the Atlanta School System was desegregated.

On July 1, 1973, Mays appointed Alonzo Crim as the first African-American superintendent of schools. Other board members and city officials were against this. But Mays used his power to protect Crim. He allowed Crim to run the school system. Mays retired from the board in 1981. A newly built school was named after him: Mays High School. It opened in 1985 to students of all races. Mays is widely seen as the most important person in the desegregation of Atlanta.

Death and Legacy

Benjamin Mays died on March 28, 1984, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was first buried in a cemetery. But in May 1995, his body was moved to Morehouse College campus. His wife, Sadie, is also buried there. Morehouse College created the Benjamin E. Mays Scholarship after his death.

Lawrence Carter, a professor, called Mays "one of the most significant figures in American history." Andrew Young said, "if there hadn't of been [sic] a Benjamin Mays there would not have been a Martin Luther King Jr." He said Mays greatly influenced King's religious thinking. Samuel DuBois Cook, a university president, called Mays "one of the great architects of the civil rights movement." He said Mays set the standard through his teaching, writing, and leadership. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Benjamin Mays on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Sites and Honors

In his home state of South Carolina, Mays was inducted into the South Carolina Hall of Fame in 1984. His childhood home was moved to Greenwood, SC. It is now a State Historic Site.

Nationally, he received the Spingarn Medal from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in 1982. He was also added to the Schomburg Honor Roll of Race Relations. This honor is given to only a few major leaders. Wiliams College created the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship in his honor. The National School Boards Association created the Benjamin Elijah Mays Lifetime Achievement Award. This award honors people who have helped urban school children.

Mays received many honorary degrees from universities. He received 40 during his life. As of 2018, he has received 56 honorary degrees.

Bates College's highest alumni award is the Benjamin E. Mays Medal. It is for alumni who have done great service to the world. Mays was the first person to receive this medal. The college also created the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professorship in 1985.

Many places are named after Mays. These include buildings, schools, streets, awards, and scholarships. He was most touched when a small Black church in Ninety Six, South Carolina, renamed itself Mays United Methodist Church.

Here are some memorials to Mays in the United States:

- Benjamin Elijah Mays High School, in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays Drive in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays Archives in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays National Memorial in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

- The Statue of Benjamin E. Mays at Morehouse College, Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

- Benjamin Mays Hall of Howard University, in Washington, D.C., U.S.

- Benjamin Mays Center of Bates College, in Lewiston, Maine, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays International Magnet School, in St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S.

- Mays House Museum, in Greenwood, South Carolina, U.S.

- Benjamin Mays Historic Site, in Greenwood, South Carolina, U.S.

- Dr Benjamin E. Mays Elementary School in Greenwood, South Carolina, U.S.

- Mays United Methodist Church, in Ninety Six, South Carolina, U.S.

- Mays Crossroads on Highway 171 in Ninety Six, South Carolina, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays Elementary Academy, in Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

- Benjamin E. Mays High School in Pacolet, South Carolina, U.S.

Efforts for the Medal of Freedom

After Mays retired in 1981, people asked President Ronald Reagan to give him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This request was turned down. In 1993, Representative John Lewis suggested that Mays be honored on a federal stamp. He also asked that Mays be given the Medal of Freedom posthumously (after his death). This request went to President Bill Clinton, but it was not acted upon.

The request was sent again to President George W. Bush. It passed both houses of Congress, but was not signed by a president. The petition was sent one more time in 2012 to President Barack Obama, but it was not awarded.

See also

- List of peace activists

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of Bates College people

- List of University of Chicago people

- Post–civil rights era in African-American history

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |