Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Schomburg Centerfor Research in Black Culture |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Type | Research library |

| Established | 1905 (as the 135th Street Branch) 1925 (as the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints) |

| Collection | |

| Items collected | Poems by Phillis Wheatley, papers of Ralph Bunche, Malcolm X, and Hiram Rhodes Revels |

| Size | 10 million |

| Other information | |

| Director | Joy L. Bivins |

| Website | Official website: http://www.nypl.org/locations/schomburg |

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a special library in New York City. It is part of the New York Public Library system. This center collects and keeps important information about people of African descent from all over the world. Think of it as a huge treasure chest of history, art, and stories.

The Schomburg Center is located in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan. It has been a key part of the Harlem community for a very long time. The center is named after Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, a scholar from Puerto Rico who was of African descent.

The center has five main parts, each focusing on different types of materials:

- The Art and Artifacts Division

- The Jean Blackwell Hutson General Research and Reference Division

- The Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division

- The Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division

- The Photographs and Prints Division

Besides being a place for research, the Schomburg Center also hosts many fun events. These include book readings, discussions, art shows, and plays. It is open for everyone to visit and learn.

Contents

A Look Back: Early History of the Center

The First Library Branch

In 1901, a rich businessman named Andrew Carnegie offered to give money to New York City. He wanted to build 65 new libraries. The city had to provide the land and take care of the buildings. The library building at 103 West 135th Street opened on July 14, 1905. It started with 10,000 books.

Ernestine Rose and the Harlem Renaissance

In 1920, Ernestine Rose, a librarian, became the head of this branch. She quickly made sure that African-American librarians were hired. Catherine Allen Latimer was the first African-American librarian hired by the New York Public Library. She worked with Rose, along with Roberta Bosely and Sadie Peterson Delaney. They worked together to help people in the community read more. They also worked with local schools and groups.

In 1921, the library held the first art show in Harlem that featured African-American artists. This became an annual event. The library soon became a very important place for the Harlem Renaissance. This was a time when African-American art, music, and literature flourished in Harlem. By 1923, this branch was the only one in New York City that hired Black librarians.

In 1924, Ernestine Rose met with important people like Arturo Alfonso Schomburg and James Weldon Johnson. They decided to focus on collecting rare books about African-American history and culture. On May 8, 1925, this special collection became a new part of the New York Public Library. It was called the Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints.

In 1926, Arturo Schomburg wanted his amazing collection of African-American books and items to be available to everyone. He wanted it to stay in Harlem. So, the Carnegie Foundation bought his collection for $10,000 and gave it to the library. Schomburg's collection showed that Black people have a rich history and culture. About 5,000 items from his personal collection were added.

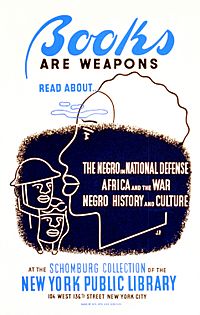

Schomburg himself became the first curator of his collection in 1932. He worked there until he passed away in 1938. In 1940, the collection was renamed the Schomburg Collection of Negro History and Literature.

|

Schomburg Center

for Research in Black Culture |

|

(2009)

|

|

| Location | 103 West 135th Street Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Architect | Charles Follen McKim |

| Architectural style | Italian Renaissance Palazzo |

| NRHP reference No. | 78001881 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 21, 1978 |

| Designated NHL | December 23, 2016 |

In 1942, Ernestine Rose retired. Dorothy Robinson Homer became the new Branch Librarian. The community specifically asked for an African-American person to take over.

The Countee Cullen Branch

After an addition was built onto the library, it became known as the Countee Cullen Library branch. The original building on 135th Street is still part of it. Dorothy Robinson Homer created a special room just for young adults. She also started the American Negro Theatre in the basement. This theater helped launch the famous play Anna Lucasta. Homer made sure the library continued to be a community hub for art, music, and drama. She also put on art shows for new, young artists of all backgrounds.

Jean Blackwell Hutson's Leadership

In 1948, Jean Blackwell Hutson became the director of the center. In 1971, a private group called the Schomburg Corporation started helping to support the center. The next year, New York City gave money to fix up the building. The center was then renamed the Schomburg Collection for Research in Black Culture. All the Schomburg collection items from other libraries were brought to this main center. In 1972, it became one of the New York Public Library's main research libraries.

In 1973, a new location was chosen for a bigger building. This spot was picked because it was close to other community groups. It was also where much of the Harlem Renaissance happened. In 1978, the original building on 135th Street was added to the National Register of Historic Places. This means it is a very important historical site.

The Modern Schomburg Center

In 1980, a new Schomburg Center building opened at 515 Lenox Avenue. In 1981, the original building on West 135th Street became a New York City landmark. In 2016, both the old and new buildings, which are now connected, were named a National Historic Landmark. This is an even higher honor for historical places.

The Roger Furman Theatre is also located inside the center.

Howard Dodson's Time as Director

Howard Dodson became the director in 1984. At that time, the Schomburg was mostly a cultural center for tourists and schoolchildren. Its research parts were mainly known by scholars. By 1984, the Schomburg's collection had grown to 5 million items. About 40,000 people visited each year. The Schomburg was already known as the most important place in the world for collections about people in Africa or of African descent.

In 1991, more additions were completed at the Schomburg Center. The new building on Malcolm X Boulevard was expanded. It now included an auditorium and a connection to the old landmark building. The Art and Artifacts Division and the Moving Image and Recorded Sound Division moved into the old building. In 2000, the Schomburg Center held an exhibit called "Lest We Forget: The Triumph Over Slavery." This exhibit later traveled around the world. In 2007, the building was renovated and expanded again. By 2010, the center had 120,000 visitors each year.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad's Leadership

In 2011, Khalil Gibran Muhammad became the fifth director of the Schomburg. He wanted the Schomburg to be a key place for young adults. He also wanted it to work closely with the local community. His goal was to help people feel proud of their history. He also wanted the center to be a way to learn about the history of Black people worldwide.

Kevin Young's Time as Director

On August 1, 2016, Kevin Young, a poet and professor, became the director. During his four years, the number of visitors grew by 40%. It reached 300,000 visitors each year. He helped raise over $10 million in money and gifts. He also got several important collections for the center. These included the papers of James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte, and the couple Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. A big renovation of the Schomburg Center buildings was finished in 2017. This project added new gallery and research areas. It also improved the Langston Hughes Auditorium and the Rare Books Reading Room.

Kevin Young left the Schomburg at the end of 2020. He became the director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Joy Bivins' Leadership (2021–Present)

In 2021, Joy Bivins was chosen as the new director of the Schomburg Center. In 2022, the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York provided $8 million for more renovations. This work included making the buildings more energy-efficient and safer. It also replaced windows and the roof. The New York Public Library plans to hold many events in 2025. These events will celebrate the Schomburg Collection's 100th anniversary.

What's in the Collection?

By 1998, the Schomburg Collection was known as having the rarest and most useful items about African-American culture. It is still seen as the most important place for African-American materials in the United States. As of 2010, the collection had 10 million items!

The center holds many amazing things, such as:

- A signed first edition of a book of poems by Phillis Wheatley.

- Papers from important figures like Malcolm X, Nat King Cole, and Ralph Bunche.

- Documents signed by Toussaint Louverture, a leader of the Haitian Revolution.

- A rare recording of a speech by Marcus Garvey, a Black nationalist leader.

- Musical recordings, jazz magazines, rare books, and thousands of art objects.

The collection also includes papers from groups like the International Labor Defense and the Civil Rights Congress. It has manuscripts about Slavery and Abolitionism. There are also letters and unpublished writings by Langston Hughes.

See also

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |