African Burial Ground National Monument facts for kids

Quick facts for kids African Burial Ground National Monument |

|

|---|---|

The African Burial Ground National Monument in October 2007

|

|

| Location | 290 Broadway, New York City, NY 10007 |

| Area | 0.35 acres (0.14 ha) |

| Created | February 27, 2006 |

| Visitors | 108,585 (in 2011) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | African Burial Ground National Monument |

| Designated: | April 19, 1993 |

| Reference #: | 93001597 |

| Architects: | Rodney Léon and Nicole Hollant Denis |

| Designated: | February 27, 2006 |

The African Burial Ground National Monument is a special place in Lower Manhattan, New York City. It's located near Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way. The main building connected to it is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway.

This site holds the remains of over 419 African people. They were buried here in the late 1600s and 1700s. This was once the biggest cemetery for people of African descent during the colonial era. Some of these people were free, but most were enslaved. Historians believe that between 10,000 and 20,000 people might have been buried here. In the 1700s, it was known as the "Negroes Burial Ground."

Experts have called the discovery and study of this site "the most important historic urban archaeological project in the United States." It is New York's oldest known African-American cemetery. Studies show that about 15,000 African American people were buried here over time.

Finding this burial ground brought attention to the forgotten history of enslaved Africans in early New York City. These individuals were very important in building the city. By the time of the American Revolutionary War, almost a quarter of the city's population was enslaved. New York had the second-highest number of enslaved Africans in the country, after Charleston, South Carolina.

Scholars and African-American community leaders worked together to share the importance of this site. They also pushed for its protection. The site was named a National Historic Landmark in 1993. Later, in 2006, President George W. Bush made it a national monument.

In 2003, the U.S. Congress set aside money for a memorial at the site. They also asked for the federal courthouse design to be changed to make room for it. Many people submitted ideas for the memorial. The memorial was officially opened in 2007. It honors the role of Africans and African Americans in New York City's early history and in the history of the United States. A visitor center opened in 2010. It helps people learn about the site and African-American history in New York.

Contents

Africans in Early New York City

Life Before the Revolutionary War

Slavery in the New York City area began around 1626. The Dutch West India Company brought the first enslaved Africans to New Netherland. These first arrivals included men like Paul D'Angola and Simon Congo. Their names often showed where they came from, like Angola or the Congo. This marked the start of slavery in what would become New York City, which lasted for 200 years.

The first slave auction in the city happened in 1655. It took place at Pearl Street and Wall Street. Even though the Dutch brought Africans as slaves, some could gain freedom or "half-freedom." In 1643, Paul D'Angola and others asked the Dutch West India Company for their freedom. They received it and were given land to build homes and farm. By the mid-1600s, farms owned by free Black people covered 130 acres. This area is now Washington Square Park. Enslaved Africans also had some rights, like protection from certain harsh physical punishments.

The English took over New Amsterdam in 1664. They renamed the settlement New York. The new leaders changed the rules about slavery. When the English took control, about 40 percent of New Amsterdam's small population was enslaved. The new rules were much stricter than the Dutch ones. They took away many rights and protections that enslaved people once had.

In 1697, Trinity Church took control of the city's burial grounds. They then made a rule that Black people could not be buried in churchyards. This meant Africans had to be buried outside the city limits. For much of the 1700s, the African burial ground was just north of what is now Chambers Street.

As the city grew, so did the number of slaveholders. In 1703, 42 percent of New York homes had slaves. This was more than Philadelphia and Boston combined. Most households had only a few slaves, mainly for housework. By the 1740s, 20 percent of New York's population, about 2,500 people, were slaves. Enslaved people also worked as skilled builders, sailors, and other laborers. By 1775, New York City had the most enslaved people of any northern city.

Life After the Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, the British took control of New York City in 1776. They stayed until 1783. The British offered freedom to enslaved people who escaped from their Patriot owners and joined the British side. Thousands of enslaved people came to the city seeking this freedom. In 1781, New York offered money to slave owners who let their slaves serve in the military. These slaves were promised freedom after the war.

By 1780, the African-American community in New York City grew to about 10,000. The city became a major center for free Black people in North America. After the war, Americans demanded that the British return all former slaves. However, the British refused. They evacuated 3,000 freed people with their troops in 1783. These individuals were resettled in places like Nova Scotia and England. The British agreed to pay Americans for the lost slaves instead of returning them. Other freed people left the city to avoid being recaptured.

By 1790, about one-third of the Black population in the city was free. This was partly due to individual slave owners granting freedom. The city's total population was 33,131 at that time.

In 1799, New York passed a law for the gradual end of slavery. Children born to enslaved mothers after July 4, 1799, were considered free. However, they had to work for their mother's owner as indentured servants until they reached a certain age. All people already enslaved before July 4, 1799, remained enslaved for life.

In 1817, New York's legislature set July 4, 1827, as the date for total abolition of slavery. On that day, over 10,000 enslaved people in New York State became free. There was no money paid to their former owners. Black people celebrated this day, now known as New York's Emancipation Day, with parades in New York City.

The early history of free Black people and enslaved people in New York City was later overshadowed. Many immigrants from Europe arrived in the 1800s. This greatly increased the city's population and diversity. Also, most African Americans in the city today came from the South during the Great Migration in the 1900s. Because of these changes, the early history of African Americans in colonial New York was largely forgotten.

History of the Burial Ground Site

The Negros Burial Ground

In the late 1600s, New York Town residents used a burial ground. It was located where the north graveyard of Trinity Church is today. This public burial ground was open to everyone for a fee, including enslaved Africans. Some enslaved people were buried just south of this public ground to avoid the fee.

After Trinity Church became a parish church in 1697, it started taking control of land in Lower Manhattan. This included existing public burial grounds. On October 25, 1697, Trinity Church made a rule. It said that no Black person could be buried in the churchyard after four weeks.

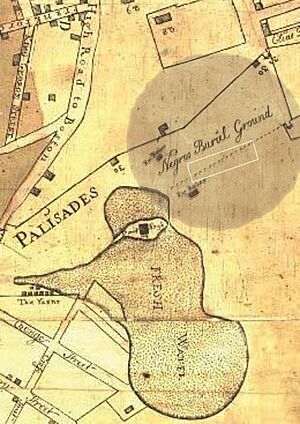

This rule meant that people of African descent needed another burial place. The "Negro's Burial Ground" was created on the edge of the town. It was just north of today's Chambers Street. It was also west of the former Collect Pond. This area was part of a land grant given to Sara Roelofs. She was an interpreter between New York and local Native American tribes. The land stayed part of her family's estate until the late 1790s. Then, the land was raised with landfill for new buildings.

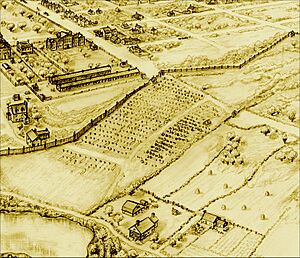

Old maps show this area as the "Negros Burial Ground." It was about 6.6 acres. It was first used around 1712 for burials of both enslaved and free Black people. The first burials might have happened in the late 1690s. This was after Trinity Church stopped African burials in the old city cemetery. The burial ground was in a shallow valley. It was surrounded by low hills and near Collect Pond. It was outside the city's northern boundary. In 1788, a riot happened because doctors were illegally digging up bodies from this burial ground for study.

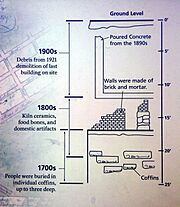

Building on the Site

After the city closed the cemetery in 1794, the area was planned for development. The land was raised with up to 25 feet of landfill in the lowest spots. This covered the cemetery, protecting the burials and the original ground level. As buildings were constructed on top of this fill, the burial ground was mostly forgotten.

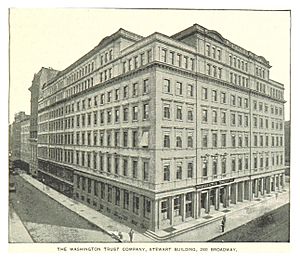

Washington Hall, a hotel, was built on part of the site from 1809 to 1812. The first large building was the A.T. Stewart Company Store. This was the country's first department store. It opened in 1846, replacing Washington Hall. Several skeletons were found when this store was being built.

Early discoveries of bones in the 1800s didn't get much attention. A homeowner named James Gemmel said that many human bones were found when his cellar was dug. He thought it was a common burial ground. In 1897, when the building at 290 Broadway was torn down, many bones were found again. Some people thought these bones were from a 1741 event where Black people faced severe punishments. Others wondered if the bones were Dutch or Native American. Many bones were taken as souvenirs.

Discovery and Community Action

On October 8, 1991, the federal General Services Administration (GSA) announced an important discovery. They found 8 complete burials during an archaeological dig. This dig started in May 1991 for a new federal office building at 290 Broadway. The building was later named the Ted Weiss Federal Building. Federal law requires checking for historical sites before building. The GSA had done a study, but it predicted no human remains would be found. This was because of the area's long history of building.

After the discovery became public, the African-American community became very concerned. The GSA tried to continue building, but the community felt they were not being listened to. They believed the discoveries needed a better plan for protection and study.

Community Protests

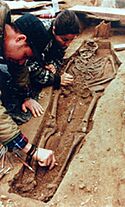

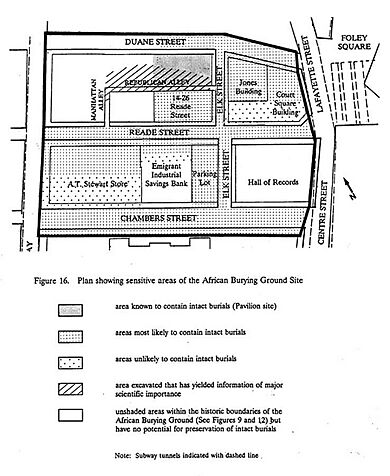

The GSA first planned to remove all remains. Within a year, they removed 419 bodies. But it became clear the burial ground was too large to fully dig up. In 1992, activists protested how the GSA was handling the site. They were especially upset when some burials were damaged during construction. The GSA stopped construction to fully check the site. They provided more money for further digging and study. The site was important because it was near New York City Hall and federal courts. Activists wanted to correct the "invisibility" of Black history in New York City.

Archaeologists studied the site for almost 12 years. But critics felt the GSA's first plan was not good enough. It didn't include a plan for what to do with the uncovered remains. Also, the African-American community in New York City was not asked for their input.

Community members, politicians, and scholars continued to protest. In 1992, the House Subcommittee on Public Works held hearings. They heard from many critics of the GSA's project. As a result, control of the burial site was given to Michael Blakey and his team at Howard University. This ensured that African-American students would help study the remains of their ancestors.

Impact of Protests

Because of the African-American community's efforts, the United States Congress passed a law. On October 6, 1992, President George H. W. Bush signed it. This law ordered the GSA to stop construction and digging on the part of the building where remains were found. It also set aside $3 million to change the building's foundation and create a memorial. The southern part of the building was removed to make space for the memorial.

Activists also pushed for the burial ground to become a landmark. They collected 100,000 signatures for the U.S. Department of the Interior. On April 19, 1993, 0.34 acres of the African Burial Ground became a National Historic Landmark. The GSA also planned programs for studying the data, preserving items, and educating the public. There was growing support for a museum at the site. The discovery and the long debate received national media attention. This raised interest in public archaeology projects.

Theresa Singleton, an archaeologist, noted the impact. She said, "The media exposure has created a larger, national audience for this type of research." She added that many scholars and people were interested in African-American archaeology. This interest had grown significantly.

Government and private builders learned an important lesson. They realized they needed to include descendant communities in their digs. This is especially true when human remains are involved. The findings at the burial ground showed how much of slavery's history had been lost. African Americans had not been recognized as a major part of early New York history until then.

Site Studies

In total, the complete remains of 419 African men, women, and children were found. They were buried individually in wooden boxes. There were no mass burials. Almost half of them were children under 12. This shows the high death rate at that time. Historians believe that over the years, 15,000 to 20,000 Africans were buried in Lower Manhattan. This was the largest colonial-era cemetery for enslaved African people. It is also possibly the largest and oldest collection of American colonial remains of any ethnic group. Some burials included items related to African traditions.

The work of digging up and studying these remains was called "the most important historic urban archaeological project in the United States." These remains represent thousands of people. They show the "critical" role Africans played in building New York City and the nation.

The Howard University team worked with the community. They identified four main questions the community wanted answered from studying the remains:

- Where did the buried people come from?

- How did their culture change from African to African-American?

- What was their quality of life like as enslaved people?

- How did they resist being enslaved?

Before the monument was built, the burial ground had faced a lot of damage. Archaeologists found much industrial waste and broken pottery during the dig. They concluded that Europeans used the burial ground as a dumping site in the 1700s. The site was also robbed and looted. In April 1788, the Doctor Riot spread through New York City. Doctors would steal bodies from graves to study them because there weren't enough bodies for medical training. Many of these stolen bodies came from the African Burial Ground.

Some bodies had items buried with them. These were part of personal and cultural rituals. One example is the silver pendant shown in the picture. Some skulls showed filed teeth, which was an African cultural practice. Howard University did forensic studies. They looked at the remains for signs of nutrition, diseases, and general living conditions for enslaved and free Black people.

After the studies, the 419 skeletons were reburied on October 4, 2003. This happened in a ceremony called the "Rites of Ancestral Return." They were placed in wooden coffins made in Ghana and lined with Kente cloth. These were then placed in 7 large stone coffins and buried in 7 mounds. The heads faced west. This emotional ceremony included events in several cities. Thousands of people attended the reburial and commemoration.

The Memorial

Building and Opening

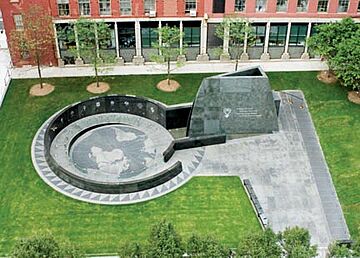

The GSA held a design competition for the memorial. They worked with community leaders. Over 60 ideas were submitted. The winning design was by Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis. It was chosen in April 2005.

The memorial has two main parts. There's the 24-foot tall Ancestral Chamber and the large Circle of the Diaspora. The height of the Ancestral Chamber shows how deep the graves were found. It is made from green granite from Africa. It has an engraved heart-shaped Sankofa symbol from West Africa. This symbol means "Learn from the past to prepare for the future."

The Circle of the Diaspora shows a map of the Atlantic area. This refers to the Middle Passage, the journey enslaved people took from Africa to North America. It is built with stone from Africa and North America. This symbolizes the two worlds coming together. The Door of Return refers to "The Door of No Return." This was the name for slave ports in West Africa. From these ports, many people were taken after being sold, never to see their homeland again. The memorial helps connect African Americans to their ancestors' origins.

On February 27, 2006, President George W. Bush officially named the burial site the 123rd National Monument. The government also announced plans for an $8 million memorial. The Burial Grounds became part of the National Park Service. The memorial was opened on October 5, 2007. Mayor Michael Bloomberg and poet Maya Angelou were there. As part of the event, Elk Street was officially renamed African Burial Ground Way.

Visitor Center

On February 27, 2010, a visitor center opened for the African Burial Ground National Monument. It is located in the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway. This building was built over part of the archaeological site.

The visitor center has a permanent exhibit called "Reclaiming Our History." It explains the importance of the burial site. It includes a life-sized scene showing a funeral for an adult and a child. Other parts of the exhibit explore the lives of Africans in early New York. It also shows how the community successfully protected the burial ground. The visitor center has a theater and a shop. The National Park Service manages the center. They also organize cultural events throughout the year.

Lasting Impact

The discoveries at the African Burial Ground have changed how people think about early African-American history. This is true for New York and the entire nation. Many new books have been published on this topic. In 2005, the New-York Historical Society held its first exhibit ever on slavery in New York. It was so popular that it was extended into 2007.

When the visitor center opened in 2010, Edward Rothstein wrote about the change. He said, "A new understanding has emerged about slavery's history in New York City." He noted that in the 1700s, enslaved people made up about a quarter of New York's workforce. This made the city one of the largest slave-holding urban centers in the colonies.

See also

In Spanish: Monumento nacional Cementerio Africano para niños

In Spanish: Monumento nacional Cementerio Africano para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |