Dutch West India Company facts for kids

Company flag

|

|

|

Native name

|

Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie

|

|---|---|

| Founded | June 3, 1621 |

| Defunct | January 1, 1792 |

|

Number of locations

|

Amsterdam, Hoorn, Rotterdam, Groningen and Middelburg |

|

Key people

|

Heeren XIX |

| Products | Gold, Slaves, Sugar, Salt |

The Dutch West India Company (often called the GWC) was a big trading company from the Netherlands. It was created by Dutch business people and investors from other countries. The company received a special permission, called a charter, on June 3, 1621.

This charter gave the GWC the sole right to trade in the Dutch West Indies. It also controlled Dutch involvement in the trade of people for forced labor across the Atlantic Ocean. The company's area of operation included West Africa and the Americas, stretching to the Pacific Ocean.

The main goal of the GWC was to stop other countries, especially Spain and Portugal, from competing with Dutch trade. The company played a big part in the Dutch colonization of the Americas during the 1600s. This included places like New Netherland.

From 1624 to 1654, the GWC took over Portuguese land in northeast Brazil. However, they were eventually forced out of Dutch Brazil after strong resistance. The company faced many challenges. It was reorganized in 1675 with a new charter, focusing heavily on the trade of people for forced labor. This "new" company lasted for over a century. It lost most of its valuable assets after the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.

Contents

How the Company Started

When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was set up in 1602, some traders in Amsterdam didn't like its rules. The VOC had a monopoly, meaning it was the only company allowed to trade in the East. These traders wanted to find new routes to Asia to avoid the VOC's control.

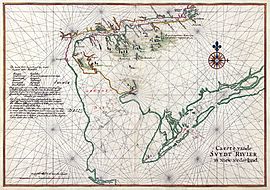

In 1609, an English explorer named Henry Hudson worked for the VOC. He sailed along the coast of New England and up the Hudson River. He was looking for a Northwest Passage to Asia, but he didn't find one. Later, other traders focused on finding a route around South America to avoid the VOC's monopoly.

One of the first Dutch sailors to trade with Africa was Balthazar de Moucheron. Trading with Africa offered chances to set up trading posts. These posts were important for starting negotiations and trade. In 1612, the Dutch built a fort in Mouree (now Ghana) on the Dutch Gold Coast.

Trade with the Caribbean for salt, sugar, and tobacco was difficult because of Spain. Spain wanted peace with the Dutch Republic. But they said the Dutch had to stop trading with Asia and America. Spain refused to sign a peace treaty if a West India Company was created.

At this time, the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) was happening between Spain and the Dutch Republic. A Dutch leader named Johan van Oldenbarnevelt suggested a temporary break in fighting, called the Twelve Years' Truce. During this truce, Dutch ships sometimes sailed under a foreign flag in South America.

Ten years later, another Dutch leader, Maurice, Prince of Orange, wanted to continue the war with Spain. He also wanted to shift attention from Spain to the Dutch Republic. In 1619, Oldenbarnevelt was executed. Two years later, the truce ended, and the Dutch West India Company was finally established.

The GWC received its official charter from the States General of the Netherlands in 1621. However, the idea for the company had been around much earlier. It was delayed because of the Twelve Years' Truce with Spain.

How the West India Company Worked

The Dutch West India Company was set up in a similar way to the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The GWC had five main offices, called "chambers." These were in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Hoorn, Middelburg, and Groningen. The Amsterdam and Middelburg chambers were the most important.

The company was run by a board of 19 members, known as the Heeren XIX (the Nineteen Gentlemen). Decisions often involved a lot of discussion because different regions had their own representatives. For example, Amsterdam had 8 representatives, and Zeeland had 4. Each region had its own chamber and directors. The company's charter was valid for 24 years.

It took until 1623 to get enough money for the company. The Dutch government and the VOC promised one million guilders to help. Some people thought that Jewish investors played a big role in starting the company. But research shows they had a smaller role at first, which grew when the Dutch were in Brazil.

People from the Spanish Netherlands who followed the Calvinist religion invested a lot in the GWC. However, individual investors were slow to put their money in the company in 1621. This was partly because shareholders had little say in how the directors ran things. The directors of the VOC even invested money in the GWC without asking their own shareholders.

To attract investors from other countries, the GWC offered them the same rights as Dutch investors. This brought in shareholders from France, Switzerland, and Venice. By 1623, the GWC had about 2.8 million florins. This was less than the VOC's starting money, but still a large amount. The GWC had 15 ships for trade along the west African coast and in Brazil.

Unlike the VOC, the GWC was not allowed to use its own military troops at first. When the Twelve Years' Truce ended in 1621, the Dutch Republic was free to restart its war with Spain. A "grand design" was planned to take over Portuguese colonies in Africa and the Americas. The goal was to control the sugar and forced labor trade.

When this plan didn't fully work, attacking enemy ships became a major goal for the GWC. Merchant ships were armed with guns and soldiers to protect themselves from Spanish ships. In 1623, most ships had 40 to 50 soldiers. These soldiers might have helped to capture enemy ships.

At first, the company struggled with its expensive projects. Its leaders then focused on capturing enemy ships and their goods. The GWC's biggest success was when Piet Heyn captured the Spanish silver fleet in 1628. This fleet was carrying silver from Spanish colonies to Spain. He also took sugar from Brazil and other valuable goods.

Capturing enemy ships was the most profitable activity for the GWC in the late 1620s. But the company's directors realized this wasn't a good long-term plan. So, they decided to try again to take over Spanish and Portuguese land in the Americas. They chose Brazil as their next target.

There were disagreements among the directors from different parts of the Netherlands. Amsterdam was less supportive of the company's plans. But other cities were very keen on taking over territory. They sent a fleet to Brazil, capturing Olinda and Pernambuco in 1630. This was their first attempt to create a Dutch Brazil, but they couldn't hold these places due to strong Portuguese resistance.

Company ships continued to capture enemy vessels in the Caribbean. They also took important land resources, like salt mines. The company's general lack of success caused its shares to drop. The Dutch and Spanish then started peace talks again in 1633.

In 1629, the GWC allowed investors in New Netherland to start large land grants called patroonships. This was made possible by the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions. The goal of patroonships was to help more people move to the colony. Investors received land grants for about 50 people aged 15 or older. These grants were mainly in the New Netherland region.

Patroon investors could expand their land as far as 4 miles along a shore or river. Rensselaerswyck was the most successful Dutch West India Company patroonship.

The New Netherland area included New Amsterdam (which is now New York City). It covered parts of what are now New York, Connecticut, Delaware, and New Jersey. Other settlements were made in the Netherlands Antilles and in South America, including Dutch Brazil, Suriname, and Guyana. In Africa, posts were set up on the Dutch Gold Coast (now Ghana), the Dutch Slave Coast (now Benin), and briefly in Angola.

This system was a bit like the old feudal system. Patrons had a lot of power to control the overseas colony. In the Americas, fur (in North America) and sugar (in South America) were the most important trade goods. African settlements traded gold, ivory, and people for forced labor. These people were mainly sent to plantations in the Antilles and Suriname.

Challenges and Decline

In North America, the settlers had trouble getting enough people to live in the colony of New Netherland. They also struggled to defend themselves against local Native American groups. Only Kiliaen Van Rensselaer managed to keep his settlement in the north along the Hudson River. The GWC's main focus then shifted to Brazil.

It wasn't until 1630 that the West India Company managed to conquer a part of Brazil. They founded the colony of New Holland (with its capital in Mauritsstad, now Recife). This meant taking over Portuguese lands in Brazil. However, the ongoing war in Brazil cost the company so much that it was always close to going bankrupt. In fact, the GWC went bankrupt in 1636.

By 1645, the GWC was in a very bad situation because of the war in Brazil. An attempt to use the profits from the VOC to cover the GWC's losses failed. The VOC directors didn't want to help. Merging the two companies also didn't work. Amsterdam was not willing to help much because it wanted peace and good trade with Portugal. This attitude from Amsterdam was a big reason why the colony was eventually lost.

In 1647, the company restarted with 1.5 million guilders, which came from the VOC. The Dutch government took responsibility for the war in Brazil.

Because of the Peace of Westphalia treaty, the GWC was no longer allowed to attack Spanish ships. Many merchants from Amsterdam and Zeeland then started working with traders from other European countries. In 1649, the GWC gained a monopoly on gold and the trade of people for forced labor with the kingdom of Accra (now Ghana).

In 1662, the GWC signed several contracts with the Spanish Crown. These contracts meant the Dutch had to deliver 24,000 people for forced labor. The GWC's influence in Africa was threatened during the Second Anglo-Dutch War and Third Anglo-Dutch War. But English efforts to remove the Dutch from the region were not successful.

The first West India Company slowly declined. Its end in 1674 was not a surprise. The company managed to last for twenty more years mainly because of its valuable possessions in West Africa, which included the trade of people for forced labor.

The New West India Company

When the GWC couldn't pay its debts in 1674, the company was closed down. But there was still a high demand for trade with the West, especially the trade of people for forced labor. Also, many colonies still existed. So, it was decided to create the Second Chartered West India Company in 1675. This new company had the same trading area as the first one.

The new company took over all the ships, forts, and other assets from the old company. The number of directors was reduced from 19 to 10. The new GWC had a capital of over 6 million guilders around 1679. Most of this money came from the Amsterdam Chamber.

From 1694 to 1700, the GWC fought a long conflict against the Eguafo Kingdom along the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana). These Komenda Wars involved many neighboring African kingdoms. They led to the trade of gold being replaced by the trade of people for forced labor.

After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, it became clear that the Dutch West India Company could no longer defend its own colonies. Places like Sint Eustatius, Berbice, Essequibo, Demerara, and some forts on the Dutch Gold Coast were quickly taken by the British. In 1791, the Dutch government bought the company's shares. On January 1, 1792, all the lands once controlled by the Dutch West India Company became part of the Dutch Republic. Around 1800, there was an attempt to create a third West Indian Company, but it was not successful.

See also

In Spanish: Compañía Neerlandesa de las Indias Occidentales para niños

In Spanish: Compañía Neerlandesa de las Indias Occidentales para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |