Twelve Years' Truce facts for kids

The Twelve Years' Truce was a time of peace during the Eighty Years' War. This war was fought between Spain and the Dutch Republic. The truce began in Antwerp on April 9, 1609. It lasted for twelve years, ending on April 9, 1621.

During this time, countries like France started to see the Dutch Republic as an independent nation. However, Spain saw the truce as a short break. They were tired from fighting and had problems at home. Spain did not officially recognize Dutch independence until 1648. This was after the Treaty of Westphalia. The truce allowed Philip III of Spain to focus on other issues. It also helped Archdukes Albert and Isabella strengthen their rule. They also brought back the Counter-Reformation in the Southern Netherlands.

Contents

Why the Truce Happened

The Dutch Republic had won many battles in the 1590s. After Antwerp fell in 1585, Philip II of Spain ordered his army to fight elsewhere. They first went after the Spanish Armada. Then they fought against France to stop Henry IV from becoming king. He was a Protestant.

Because of this, Spain's army in Flanders was mostly defending itself. Spain could not afford to fight on three fronts. So, Philip II had to stop payments in 1596. The Dutch leader, Stadtholder Maurice, used this chance well. His army surprised Breda in 1590. They took Deventer, Hulst, and Nijmegen the next year. In 1594, they captured Groningen. By then, Spain's army had lost most of its key places north of the great rivers.

Around 1600, the war became a stalemate. This means neither side could win easily. After Philip III became king of Spain in 1598, his army tried to attack the Dutch Republic. They lost a battle at Battle of Nieuwpoort in 1600. But they did stop the Dutch from invading Flanders.

The long siege of Ostend (1601–1604) showed how balanced the power was. Both sides spent huge amounts of money and effort. The town was completely destroyed. Ambrogio Spinola eventually captured Ostend in 1604. But Spain lost Sluis in return.

Meanwhile, Spain had made peace with two other enemies. In 1598, France and Spain ended their war. In 1604, England and Spain also made peace. These treaties allowed Spain to focus all its power on the Dutch. They hoped to win a big victory.

In 1605, Spinola attacked the Dutch heartland. This was the first time since 1594. By 1606, the Spanish army had captured several towns. This was despite Maurice of Nassau's efforts. However, Spain's successes came at a high cost. They did not get the quick victory they wanted. Also, the Dutch East India Company was taking over Portugal's spice trade. They set up bases in the Moluccas. This meant the war could spread to Spain's overseas empire.

On November 9, 1607, Philip III announced he could not pay his debts. Both sides were exhausted from decades of war. They were finally ready to talk about peace.

How the Truce Was Agreed Upon

The two sides began quiet talks in 1606. In March 1607, Archduke Albert asked Father Jan Neyen to find out what was needed for official talks. Neyen had been Protestant but became Catholic. He still had access to Maurice of Nassau. This made him a good go-between. Neyen traveled between Brussels and The Hague. He pretended to visit his mother.

The Dutch government, the States-General, wanted Spain to first recognize their independence. Albert agreed to this, but with some doubts. On April 12, 1607, the Dutch and Spanish Netherlands agreed to a ceasefire. It would last eight months and start on May 4. This ceasefire was later extended to include fighting at sea.

It was hard to get Philip III to agree. The king was upset that Albert had given in on independence. Only Spain's desperate financial situation made him agree. The ceasefire was extended many times. This allowed for the talks that led to the Twelve Years' Truce.

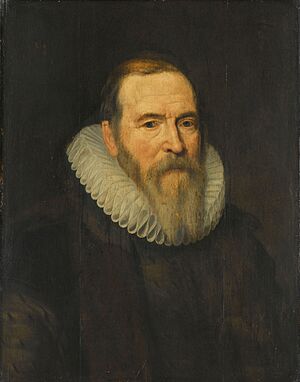

The peace conference started in The Hague on February 7, 1608. The talks took place in the Binnenhof. This room is now called the Trêveszaal. Maurice of Nassau did not attend. So, his cousin, William Louis of Nassau, led the Dutch team. He was the Stadtholder of Friesland. The main Dutch negotiator was Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. He was a very important lawyer.

Ambrogio Spinola led the Spanish Netherlands team. He was helped by Neyen and other officials. The King of Spain did not send a separate team. The Archdukes' delegates spoke for him.

Many countries sent people to the conference. France's team was led by Pierre Jeannin. England's team was led by Ralph Winwood. King Christian IV of Denmark sent his future leader, Jacob Ulfeldt. Other mediators came from different German states. Most of these delegates left as the talks went on. Only the French and English stayed until the end.

The conference could not agree on a full peace treaty. It ended on August 25. The two sides could not agree on trade in colonies or on religion. Spain wanted the Dutch to stop sailing south of the Equator. This was to protect the Spanish Empire. But the Dutch, who relied on trade, refused. This led Hugo Grotius to write his famous book Mare Liberum. It defended the Dutch right to trade freely.

The Dutch also refused Spain's demand for religious freedom for Catholics in the Republic. They saw this as Spain interfering in their country. Despite these problems, the French and English mediators convinced both sides to agree to a long truce. This would keep the peace but avoid the difficult topics. After thinking about different lengths, they settled on twelve years.

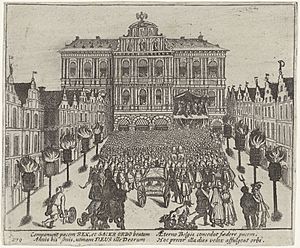

Formal talks started again on March 28, 1609, in Antwerp City Hall. On April 9, both teams signed the agreement. Getting it approved was hard. In the Dutch Republic, towns like Amsterdam worried about their trade. The province of Zeeland did not want to lose money from privateering. They also insisted on keeping the blockade of the Scheldt river. Philip III had his own reasons to refuse. It took several trips from the Archdukes' court before he finally approved the treaty on July 7, 1609.

What the Truce Said

The Spanish agreed to treat the Dutch Republic as an independent state during the truce. The exact words were a bit unclear. The Dutch version said their independence was recognized. The French text said the Republic would be treated as if it were independent.

All fighting would stop for twelve years. Both sides would control the lands they held when the agreement was signed. Their armies would no longer demand money from enemy areas. All prisoners would be freed. Privateering (piracy allowed by a government) would stop. Both sides would stop acts of piracy against the other.

Trade would start again between the former enemies. Dutch traders and sailors would get the same protection in Spain and the Spanish Netherlands as the English had. This meant they could not be punished for their beliefs, unless they caused problems for local people. The Dutch agreed to end their blockade of the Flemish coast. But they refused to allow free travel on the Scheldt river.

People who had left the Southern Netherlands could return. But they had to become Catholic. Lands taken during the war would be given back or paid for. Many noble families, including Maurice of Nassau's family, benefited from this. The details of returning lands were agreed in a separate treaty in 1610.

The agreement did not say much about trade with the Indies. It did not support Spain's claim to have sole rights to sail there. Nor did it fully support the Dutch idea that they could trade anywhere not already settled by Spain or Portugal. The truce did not improve the situation for Catholics in the Dutch Republic. It also did not help Protestants in the Spanish Netherlands. They were not actively hunted down, but they could not practice their religion in public. They also could not hold public jobs.

What Happened Next

Changes in the Dutch Republic

The most important result for the Dutch Republic was that other European countries now officially saw it as a sovereign nation. To show this, the Dutch government added a closed crown to its coat of arms. Soon after the truce began, Dutch representatives in Paris and London became full ambassadors. The Republic also started diplomatic ties with Venice, Morocco, and the Ottoman Empire. They set up a network of consuls in major ports.

On June 17, 1609, France and England signed a treaty. It guaranteed the Dutch Republic's independence. To protect its interests in the Baltic Sea, the Dutch signed a defense agreement with the Hanseatic League in 1614. This was to stop Danish attacks.

The truce did not stop Dutch colonial expansion. The Dutch East India Company set up a base on Solor island. They founded the city of Batavia on Java island. They also gained a foothold on the Coromandel Coast in Pulicat. In the New World, the Republic encouraged settlement in New Netherland. The Dutch merchant fleet grew quickly. It started new trade routes, especially in the Mediterranean.

The official ban on trade with the Americas ended. But the colonists there created their own unofficial ban. This limited Dutch trade with Caracas and the Amazon region. Temporary problems in the Indies caused the price of Dutch East India Company shares to drop. They went from 200 in 1608 to 132 after the truce began. Trade from Zeeland to the Southern Netherlands also fell sharply. However, ending the Dutch blockade of Antwerp helped trade in Flemish textiles. The Flemish textile industry also saw a comeback.

Despite the truce, in 1614, Dutch Captain Joris van Spilbergen sailed past the Strait of Magellan. He raided Spanish settlements on the coasts of Mexico and South America. He fought the Spanish at Callao, Acapulco, and Navidad.

In the Dutch Republic, ports benefited from more trade. But brewing towns like Delft and textile centers like Leiden suffered. They faced competition from cheaper goods made in the Spanish Netherlands.

Religious and Political Disputes

During the Truce, two main groups appeared in the Dutch Republic. Their differences were about religion and politics. The Dutch Reformed Church faced a disagreement. This was about the ideas of Jacobus Arminius and Franciscus Gomarus on predestination.

Arminius had less strict views. These ideas appealed to wealthy merchants in Holland. They were also popular among the leaders who controlled Holland's politics. This was because Arminius's ideas offered a church that the state could control. Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and Hugo Grotius were strong supporters of Arminius.

Gomarus had strict views. He wanted a church that was independent of outside control. His ideas appealed to workers in manufacturing towns. They also appealed to exiles from the Southern Netherlands. These people were not part of the political power. This added a social conflict to the religious debate.

In many towns, church groups split. Some were Remonstrants, who wanted to soften the strict Calvinist rules. Others were Counter-Remonstrants, who insisted on strict rules. On September 23, 1617, Stadtholder Maurice of Orange openly supported the Counter-Remonstrants. Maurice and many Counter-Remonstrants had mixed feelings about the truce. Maurice wanted full independence for the Dutch Republic. He wanted to continue the war until Spain was totally defeated. This would ensure the Republic's freedom.

To push their ideas, Remonstrant leaders used their power. They hired soldiers with the "Sharp Resolution" of August 4, 1617. This allowed city governments to raise their own armies. These were called waardgelders. This was outside the main army. Maurice and other provinces immediately protested. They said the Union of Utrecht agreement did not allow cities to raise troops without the States General's approval.

The Sharp Resolution also said that federal army units paid by Holland owed their main loyalty to Holland. This was a repeat of Holland's old idea that provinces were fully sovereign. They saw the Union as just a group of sovereign provinces. Maurice and the other provinces (except Utrecht) now said the States General had the highest power. This was for common defense and foreign policy.

Maurice then got support from five provinces against Holland and Utrecht. They voted to disband the waardgelders. This passed on July 9, 1618, with five votes to two. Holland and Utrecht voted against it. Van Oldenbarnevelt and Grotius then made a mistake. They argued that the Union treaty required everyone to agree. They sent people to the federal troops in Utrecht. These troops were supposed to disarm the waardgelders. Oldenbarnevelt's people told the troops their first loyalty was to the province that paid them. They should ignore the stadtholder's orders if there was a conflict.

Their opponents saw this as treason. Prince Maurice brought more federal troops to Utrecht. He started disarming the waardgelders there on July 31, 1618. There was no resistance. The political opposition to his actions fell apart. Van Oldenbarnevelt's ally in Utrecht, Gilles van Ledenberg, fled to Holland.

On August 29, 1618, Maurice had Oldenbarnevelt and other Remonstrant leaders arrested. He then removed many Remonstrant leaders from city governments in Holland. He replaced them with Counter-Remonstrant supporters. These were often new, rich merchants with little government experience. These changes were a big political shift. They made sure Maurice's Orangist government would control the Republic for the next 32 years. From then on, the stadtholder, not the Advocate of Holland, would lead the Republic.

Oldenbarnevelt was tried and executed. Others, like Grotius, were jailed in Castle Loevestein. Meanwhile, the Synod of Dort supported the strict view of predestination. It declared Arminianism a heresy. Arminian religious thinkers like Johannes Wtenbogaert went into exile. There, they set up a separate Remonstrant Church.

Changes in Spain

In Spain, the truce was seen as a big defeat. Spain had lost politically, militarily, and in terms of its image. The truce was not good for Spain's reputation. The Dutch seemed to gain the most. Spanish advisors did not want to renew the truce. They wanted to protect Spain's image as a great power and restart the war.

Spain found parts of the 1609 truce unacceptable. These included the virtual recognition of Dutch independence. Also, the closure of the Scheldt river to Antwerp's trade was a problem. And they disliked the Dutch trading in Spanish and Portuguese colonial areas. A defeat for Spain was mainly a defeat for Castile. Castile was the region that provided the policies and support for the empire.

However, for the time it lasted, the truce allowed Philip and the Duke of Lerma to step back from the war in the Low Countries. They could focus on Spain's internal problems. Still, Philip also wanted to end the truce by starting the war again.

Changes in the Southern Netherlands

The Southern Netherlands benefited from the truce. Farming could finally recover from the war's damage. The Archdukes' government encouraged reclaiming land that had been flooded during the fighting. They also supported draining the Moeren, a marshy area. This helped farming recover and led to a small increase in population. Fixing damaged churches and buildings also created demand for work.

Industries, especially luxury goods, also recovered. Other areas, like textiles and breweries, benefited from lower wages than in the Dutch Republic. However, international trade was hurt by the closure of the Scheldt river. The Archdukes planned to bypass this blockade. They wanted to build canals linking Ostend to Ghent and the Meuse to the Rhine. To fight poverty in cities, the government supported creating a network of mounts of piety. These were like pawn shops based on the Italian model.

Meanwhile, the Archdukes' government made sure the Counter-Reformation succeeded in the Spanish Netherlands. Most Protestants had already left the region by then. Under new laws passed after the truce, any remaining Protestants were tolerated. But they could not worship in public. Religious debates were also against the law. The decisions of the Third Provincial Council of Mechelen in 1607 were also made official. Through these actions and by appointing skilled bishops, Albert and Isabella laid the groundwork for the Catholic faith to become strong among the people.

End of the Truce

More than once, it seemed the truce would break down. A crisis over who would rule the duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg caused big problems. This led to tensions during the siege of Jülich in 1610 and fights that led to the Treaty of Xanten in 1614.

Petrus Peckius the Younger tried to renew the truce in 1621, but he failed.

|

See also

In Spanish: Tregua de los doce años para niños

In Spanish: Tregua de los doce años para niños

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |