Kingdom of Kongo facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Kingdom of Kongo

Wene wa Kongo or Kongo dya Ntotila

Reino do Congo |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1390–1914 | |||||||||||||||

The "Kingdom of Congo" (now usually rendered as "Kingdom of Kongo" to maintain distinction from the present-day Congo nations)

|

|||||||||||||||

| Status | Sovereign kingdom (1390–1857) Vassal of the Kingdom of Portugal (1857–1910) Subject of the First Portuguese Republic (1910–1914) |

||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mbanza-Kongo (São Salvador), Angola | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Kikongo Portuguese |

||||||||||||||

| Religion | Bukongo Roman Catholicism Antonianism (1704–1708) |

||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1390–1420 (first)

|

Lukeni lua Nimi | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1911–1914 (last)

|

Manuel III of Kongo | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Ne Mbanda-Mbanda | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

|

• Conquest of Kabunga

|

1390 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Battle of Mbumbi

|

1622 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Battle of Mbanda Kasi

|

1623 | ||||||||||||||

| 29 October 1665 | |||||||||||||||

| 1665–1709 | |||||||||||||||

|

• Reunification

|

February 1709 | ||||||||||||||

|

• Vassalage

|

1861 | ||||||||||||||

| 1884–1885 | |||||||||||||||

|

• Abolishment

|

1914 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| c. 1650 | 129,400 km2 (50,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

|

• c. 1650

|

appx 500,000 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Nzimbu shells and Lubongo (Libongo, Mbongo), Mpusu cloth | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Angola Democratic Republic of the Congo Republic of the Congo Gabon |

||||||||||||||

The Kingdom of Kongo was a powerful kingdom in central Africa. It existed from around 1390 to 1914. Today, its lands are part of northern Angola, the western Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, and southern Gabon.

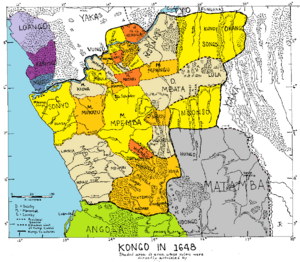

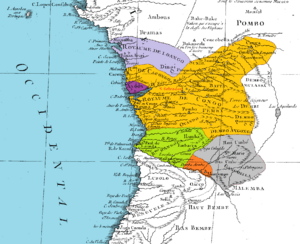

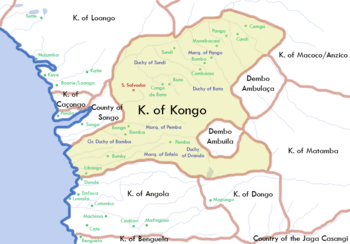

At its largest, the kingdom stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Kwango River in the east. It went from the Congo River in the north to the Kwanza River in the south. The kingdom had several main areas ruled by the Manikongo. This title means "lord or ruler of the Kongo kingdom." Kongo also influenced nearby kingdoms like Ngoyo and Loango.

Kongo was an independent country for a long time. From 1862 to 1914, it was sometimes a vassal state of Portugal. This means it was partly controlled by Portugal. In 1914, after a revolt, Portugal ended the kingdom's rule. The title of King of Kongo was brought back later, but it was just an honor. The kingdom's lands became part of Portuguese, Belgian, and French colonies. Today, some groups like the Bundu dia Kongo want to bring the kingdom back.

Contents

- History of the Kongo Kingdom

- How the Kingdom Started

- Growing the Kingdom's Power

- Royal Family Rivalries

- Kongo Under the House of Kwilu

- Kongo Under the House of Nsundi

- Royal Family Divisions and the House of Kwilu Returns

- Kongo Under the House of Kinlaza

- Kongo Civil War

- Turmoil and Rebirth

- 18th and 19th Centuries

- New Nobles and Trade Changes

- Military Structure

- Political Structure

- Economic Structure

- Art of the Kongo Kingdom

- Social Structure

- See also

History of the Kongo Kingdom

We know about Kongo's early history from stories passed down orally. These stories were first written down in the late 1500s. Missionaries like Giovanni Cavazzi da Montecuccolo recorded many details in the 1600s. Modern researchers also collected these traditions.

How the Kingdom Started

Before Kongo was founded, the area had many smaller kingdoms. These included Nsundi, Mpangu, and Mbata. The central area was called Mpemba Kasi.

According to Kongo stories from the 1600s, the kingdom began in Vungu, north of the Congo River. Its power grew across the river to Mpemba Kasi. The rulers built their power along the Kwilu valley. Their leaders were buried in a sacred place. A missionary visiting in the 1650s said this site was so holy that looking at it was dangerous.

Around 1375, Nimi a Nzima, the ruler of Mpemba Kasi and Vungu, made an alliance. He joined with Nsaku Lau, the ruler of the Mbata Kingdom. Nimi a Nzima married Nsaku Lau's daughter. This alliance meant they would help each other's families stay in power. Mbata might have been the stronger partner at first. Its ruler had the title "Grandfather of the King of Kongo."

The son of Nimi a Nzima and Nsaku Lau's daughter was Lukeni lua Nimi. He ruled from about 1380 to 1420. He started the expansion that created the Kingdom of Kongo. Lukeni lua Nimi built a new base on Mongo dia Kongo mountain. He made alliances with other local rulers. Two centuries later, the descendants of one ruler still remembered this conquest.

After Lukeni lua Nimi died, later rulers claimed to be part of his family, or kanda. This family was known as the Kilukeni. The Kilukeni family ruled Kongo without challenge until 1567.

Growing the Kingdom's Power

By the 1500s, the smaller kingdoms that once existed were now part of Kongo. They paid taxes to the King of Kongo. The king appointed members of the royal family or other noble families to govern these areas. These governors could then appoint their own officials. Over time, the allied provinces lost much of their power. Mbata, once a co-kingdom, became known only as "Grandfather of the King of Kongo."

The capital city, Mbanza Kongo, was very important. It was a large city in an area where most people lived far apart. Early Portuguese visitors said Mbanza Kongo was as big as the Portuguese town of Évora in 1491. By the early 1600s, the city and its surrounding area had about 100,000 people. This meant the king had many resources and soldiers nearby. This made the kingdom very strong and centralized.

When Europeans first arrived, Kongo was a well-developed state. It had a large trading network. Kongo traded copperware, iron goods, raffia cloth, and pottery. They also traded natural resources and ivory. The people of Kongo spoke the Kikongo language. The eastern regions were especially known for making cloth.

First Contact with Portugal and Christianity

In 1483, the Portuguese explorer Diogo Cão reached the African coast. He left some of his men in Kongo and took Kongo nobles back to Portugal. He returned in 1485 with the nobles. The king, Nzinga a Nkuwu, decided to become Christian. He sent a large group of nobles to Portugal to learn more. They studied Christianity and learned to read and write for almost four years.

In 1491, this group returned with Cão, along with Catholic priests and soldiers. King Nzinga a Nkuwu and his nobles were baptized. The king took the Christian name João I, honoring Portugal's king.

João I ruled until about 1509. His son, Mvemba a Nzinga, became king. Afonso faced a challenge from his half-brother. Afonso said he won a battle against his brother because of a vision of the cross and the Virgin Mary. After this, he created a coat of arms for Kongo. While King João I later went back to his old beliefs, Afonso I made Christianity the official religion of his kingdom.

King Afonso I worked to build a strong Catholic Church in Kongo. He used royal money and taxes to pay church workers. With help from Portuguese advisers, Afonso created a unique version of Christianity. It blended old Kongo beliefs with Christian ones. This mix stayed part of Kongo's culture for a long time. Afonso himself studied Christianity deeply. One Portuguese chaplain said Afonso knew more about the church than he did.

The Kongo church often lacked enough priests. So, they used many local teachers called mestres. These teachers were nobles trained in Kongo schools. They taught religion and led services for the growing Christian population. They also helped mix old and new religious ideas. For example, the Kikongo word ukisi (meaning charm or holy) was used for "holy." The Bible became the nkanda ukisi (holy book). The church was called the nzo a ukisi (holy house). European clergy often disliked these mixed traditions, but they could not stop them.

To create a strong priesthood, Afonso's son Henrique was sent to Europe. Henrique became a priest and was named bishop in 1518. He returned to Kongo in the 1520s to lead the new church. He died in 1531.

Kongo and the Slave Trade

Kongo had a system of capturing people and moving them to the capital. This helped the king collect taxes and tributes. This system also allowed Kongo to sell captives outside the country.

After a successful sugar colony started on São Tomé, Kongo became a major source of slaves. The Cantino Atlas of 1502 mentions Kongo as a slave source, but says there were few at first. Slavery existed in Kongo before the Portuguese arrived. Afonso's letters show slave markets and the buying and selling of slaves within the country. Most slaves sent to the Portuguese were likely war captives from Kongo's expansion. These wars also helped Afonso gain more power.

Early estimates said Kongo exported 4,000 to 5,000 slaves per year. Afonso and the Portuguese kings tried to control this trade. But traders from Sao Tome often broke the rules. They traded with rebels and other kingdoms. In 1526, Afonso complained about these illegal traders. He even threatened to stop the trade completely. He set up a committee to check if people were being enslaved legally.

However, Portugal wanted to control the slave trade directly. In 1575, Portugal sent an army to conquer the Kingdom of Ndongo. This was to take over its slave trade.

Royal Family Rivalries

Kongo's political life often involved strong competition for the throne. Afonso himself had to fight a major battle to become king. He described it as a war between Christians and non-Christians. But struggles for power were likely common even in the early days.

We know a lot about these struggles from what happened after Afonso died in 1542 or 1543. An investigation in 1550 showed how different groups supported various leaders. For example, Afonso's son, Pedro Nkanga a Mvemba, and his grandson, Diogo Nkumbi a Mpudi, fought for the throne. Diogo eventually overthrew Pedro in 1545. These groups were not always based on family lines. Nobles, provincial governors, and church officials were all involved.

King Diogo I skillfully removed his rivals after he became king in 1545. He faced a plot led by Pedro I, who hid in a church. Diogo respected the church's rule of asylum and let Pedro stay. But Diogo investigated the plot. The details sent to Portugal in 1552 show how plotters tried to get supporters to abandon the king.

Later, King Afonso II was killed by the Portuguese. An uprising followed, and the Portuguese candidate was killed. This allowed King Bernardo I to take the throne. King Bernardo I was killed in 1567 during an invasion by the "Jaga" people. Henrique I replaced him but was also killed fighting in the east. This left the government to his stepson, Álvaro Nimi a Lukeni lua Mvemba. He was crowned Álvaro I.

Kongo Under the House of Kwilu

Álvaro I was not directly related to the previous kings. His taking the throne during the Jaga invasion started a new royal line, the House of Kwilu. Álvaro fought the Jagas, who some believe were rebels or unhappy nobles. When the Jagas forced him from the capital, Álvaro asked Portugal for help. Portugal sent an expedition. As part of this, Álvaro allowed Portugal to set up a colony in Luanda, south of his kingdom. Kongo also helped Portugal in their war against the Kingdom of Ndongo in 1579.

Álvaro also tried to make Kongo more like Europe. He gave European titles to his nobles. For example, the Mwene Nsundi became the Duke of Nsundi. The capital was renamed São Salvador (Holy Savior) in Portuguese. In 1596, Álvaro's envoys convinced the Pope to recognize São Salvador as a new diocese. But the King of Portugal gained the right to choose the bishops. This caused tension between Kongo and Portugal.

Portuguese bishops in Kongo often favored European interests. They sometimes refused to appoint local priests. This made Kongo rely more on lay teachers. Kongo kings sometimes withheld money from bishops who caused problems. This control of money was important. Even Jesuit missionaries were paid by the king.

At the same time, Portuguese governors in Angola started attacking areas Kongo considered its own. This led to complaints from Kongo's rulers.

Royal Family Divisions

Álvaro I and his son, Álvaro II, also faced problems from rival noble families. To get support against some enemies, they had to give power to others. For example, Manuel, the Count of Soyo, held his office for many years. Álvaro II also gave power to António da Silva, Duke of Mbamba. António da Silva became so strong that he could choose the next king. He chose Bernardo II in 1614, then replaced him with Álvaro III in 1615. It was hard for Álvaro III to choose his own Duke of Mbamba when António da Silva died.

Kongo Under the House of Nsundi

Tensions between Portugal and Kongo grew. Portuguese governors in Angola became more aggressive. In 1617, Governor Luis Mendes de Vasconcelos used African mercenary groups called Imbangala. They attacked Ndongo and then raided southern Kongo provinces. He wanted to stop runaway slaves from hiding in Kasanze, a marshy region north of Luanda.

The next governor, João Correia de Sousa, invaded southern Kongo in 1622. This happened after Álvaro III died. Correia de Sousa claimed he could choose the King of Kongo. He was also angry that Kongo's electors chose Pedro II, a former Duke of Mbamba. Pedro II was from the Nsundi region, which gave his royal family its name, the House of Nsundi.

First Kongo-Portuguese War

The First Kongo-Portuguese War began in 1622. It started with a Portuguese attack on the Kasanze Kingdom. The army then moved to Nambu a Ngongo. Its ruler was accused of hiding runaway slaves. Even though he agreed to return some, the Portuguese attacked and killed him.

In November, the Portuguese army entered Mbamba. They won a battle at Battle of Mbumbi. But King Pedro II brought his main army, including troops from Soyo. They decisively defeated the Portuguese near Mbanda Kasi in January 1623. Portuguese merchants in Kongo were worried about their businesses. They wrote a letter criticizing the invasion.

After the defeat, Pedro II declared Angola an enemy. He wrote letters to the King of Spain and the Pope, complaining about Correia de Sousa. Anti-Portuguese riots broke out in Kongo. Portuguese people were disarmed and humiliated. But Pedro tried to protect the Portuguese merchants. He knew they had mostly stayed loyal during the war.

The Portuguese merchants in Luanda revolted against their governor. They wanted to keep their ties with Kongo. They forced João Correia de Sousa to leave. The new interim government was friendly to Kongo. They agreed to return over a thousand captured slaves.

Pedro II still wanted to remove the Portuguese from the region. He sent a letter to the Dutch Estates General. He suggested a joint attack on Angola with a Kongo army and a Dutch fleet. He offered to pay the Dutch with gold, silver, and ivory. A Dutch fleet arrived in Luanda in 1624. But the plan failed because Pedro had died. His son, Garcia Mvemba a Nkanga, became king. King Garcia I was more forgiving of the Portuguese. He refused to attack Angola, saying he could not ally with non-Catholics.

Royal Family Divisions and the House of Kwilu Returns

The early 1600s saw more political struggles in Kongo. Two noble families fought for the kingship. One was the House of Kwilu. The other was the House of Nsundi, which took power when Pedro II became king.

The House of Nsundi tried to put its supporters in important positions. Pedro II or Garcia I secured Soyo with Count Paulo, who supported the House of Nsundi. But Manuel Jordão, a supporter of the House of Kwilu, forced Garcia I to flee. He put Ambrósio I of the House of Kwilu on the throne.

King Ambrósio could not remove Paulo from Soyo. After a troubled rule, Ambrósio was killed by a mob. Alvaro IV was made king by Daniel da Silva, the Duke of Mbamba. Alvaro IV was only eleven and easily controlled. In 1632, Daniel da Silva marched on the capital to "rescue his nephew." Alvaro IV was later poisoned by Alvaro V, a member of the Kimpanzu family.

Kongo Under the House of Kinlaza

After another war, Alvaro VI became king in 1636. This started the rule of the House of Kinlaza. When Alvaro VI died in 1641, his brother, Garcia II, became king. The former House of Nsundi and House of Kwilu rivals joined to form the Kimpanzu family.

Garcia II faced several problems. One rival, Daniel da Silva, took control of Soyo. He used it as a base against Garcia II for his entire reign. This stopped Garcia II from fully uniting his power. There was also a rebellion in the Dembos region. Finally, there was the agreement Pedro II made in 1622 to help the Dutch against Portugal.

Dutch Invasion of Luanda and the Second Portuguese War

In 1641, the Dutch invaded Angola and captured Luanda easily. They wanted to restart their alliance with Kongo. Kongo and the Dutch made a formal agreement. Garcia II expelled almost all Portuguese merchants from his kingdom. Angola was again declared an enemy. The Duke of Mbamba was sent with an army to help the Dutch. The Dutch also helped Kongo militarily, in exchange for slaves.

In 1642, the Dutch helped Garcia II put down a rebellion in the Dembos region. Garcia II paid the Dutch with slaves taken from the rebels. These slaves were sent to Brazil. In 1643, a Dutch-Kongo force attacked Portuguese bases. The Dutch captured Portuguese positions. After this victory, the Dutch seemed to lose interest in conquering Angola.

The Dutch West India Company preferred to let the Portuguese stay inland. They wanted to profit from shipping, not war. So, in 1643, Portugal and the Dutch signed a peace treaty. This ended the short war. With the Portuguese out of the way, Garcia II could focus on the growing threat from the Count of Soyo.

Kongo's War with Soyo

Garcia was disappointed that the Dutch alliance didn't fully remove the Portuguese. But it allowed him to focus on Soyo. The Counts of Soyo had supported the Kinlaza family. But Count Paulo died around 1641, when Garcia became king. A rival, Daniel da Silva, took control of Soyo. He claimed Soyo had the right to choose its own ruler. Garcia never accepted this.

In 1645, Garcia II sent his son, Afonso, to fight Daniel da Silva. The campaign failed because Kongo couldn't take Soyo's fort. Afonso was captured, forcing Garcia to negotiate for his son's freedom. Italian missionaries helped with the talks. In 1646, Garcia sent another army, but they were defeated again. Because Garcia was so focused on Soyo, he couldn't fully help the Dutch against Portugal.

The Third Portuguese War

The Dutch made peace with Portugal in 1643. But they kept their military presence in Angola. Portugal then attacked Queen Njinga. When Portuguese reinforcements defeated her in 1646, the Dutch felt they had to act. Queen Njinga convinced Garcia II to send troops for another attack on the Portuguese. In 1647, Kongo troops helped defeat the Portuguese army at the Battle of Kombi. Njinga's army then surrounded all Portuguese forces inland.

A year later, Portuguese reinforcements from Brazil forced the Dutch to surrender Luanda in 1648. The new Portuguese governor, Salvador de Sá, sought peace with Kongo. He demanded the Island of Luanda, which was Kongo's source of nzimbu shells (their currency). The treaty was never officially approved, but Portugal gained control of the island. The war ended with the Dutch losing their claims in Central Africa. Queen Njinga was pushed back to Matamba. Kongo did not gain or lose much, except for a payment Garcia made to end the fighting.

The Battle of Mbwila

After Portugal returned to Luanda, they started claiming control over Kongo's southern areas. This included Mbwila, which was a vassal of Kongo but had also signed a treaty with Portugal. It was loyal to both sides.

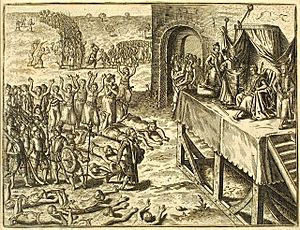

Kongo started seeking an alliance with Spain, especially after António I became king in 1661. Portugal believed he wanted to repeat the Dutch invasion, but with Spain's help. António sent envoys to other regions to form a new anti-Portuguese alliance. Portugal was also troubled by Kongo helping runaway slaves. At the same time, Portugal wanted to control Mbwila. In 1665, both sides invaded Mbwila. Their armies met at Ulanga.

At the Battle of Mbwila in 1665, the Portuguese won their first victory against Kongo since 1622. They defeated King António I, killing him and many of his officials.

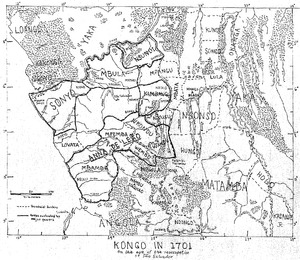

Kongo Civil War

After the battle, there was no clear successor to the throne. The country split between two rival groups: Kimpanzu and Kinlaza. They divided the country between them. Kings would take the throne and then be overthrown. During this time, many Kongo people were sold as slaves across the Atlantic. The Kongo monarchy became weaker, and Soyo became stronger.

During this chaos, Soyo gained more influence over Kongo. In desperation, Kongo's central government asked Luanda (Portuguese) to attack Soyo. In return, Kongo offered various things. The Portuguese invaded Soyo in 1670. But Soyo's forces defeated them at the Battle of Kitombo on October 18, 1670. This defeat was so big that Portugal stopped trying to control Kongo's area until the late 1800s.

The battles between the Kimpanzu and Kinlaza families continued. This plunged the kingdom into deep chaos. The fighting led to the destruction of São Salvador in 1678. The capital city was burned down, not by outside enemies, but by its own people. The city and its surrounding area became empty. People moved to fortresses on mountains.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people fleeing the conflict were sold as slaves. Some went north to Loango, then to North America and the Caribbean. Others went south to Luanda, then to Brazil. By the end of the 1600s, many wars had ended Kongo's golden age.

Turmoil and Rebirth

For almost 40 years, Kongo was in civil war. São Salvador was in ruins. The rival families lived in bases in Mbula and Kibangu. During this crisis, a young woman named Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita appeared. She claimed to be possessed by Saint Anthony's spirit. She tried to reunite the country. In 1704, she tried to convince King Pedro IV, who ruled from Kibangu. When he refused, she went to his rival, João III, at his fort in Lemba.

After being turned away there, she called her followers to move back into the capital. Thousands came, and the city was repopulated. As she became more involved in politics, she chose a new king, Pedro Constantinho da Silva. But Pedro IV's supporters captured her. She was tried for witchcraft and heresy and burned in July 1706. Her movement still controlled São Salvador until Pedro IV's army took it back in 1709.

18th and 19th Centuries

In the 1700s and 1800s, Kongo artists started making crucifixes and other religious items showing Jesus as an African. These artworks showed that Kongo saw itself as a central part of the Christian world. A story from the 1700s said that the partly ruined cathedral of São Salvador was built overnight by angels. It was lovingly called Nkulumbimbi. Pope John Paul II held a mass at this cathedral in 1992.

Manuel II of Kongo became king after Pedro IV in 1718. Manuel II ruled a restored kingdom until 1743. But Soyo's power limited Manuel's rule. Nsundi in the north also became mostly independent. Even within the remaining parts of the kingdom, there were strong rivalries.

The system of kings taking turns ruling broke down in 1764. Álvaro XI, a Kinlaza, drove out the Kimpanzu king Pedro V. Pedro and his successor kept a separate court. A regent for Pedro's successor claimed the throne in the 1780s. He fought against José I, a Kinlaza king. José won a huge battle at São Salvador in 1781, with 30,000 soldiers. José's power was limited, as he didn't control all the Kinlaza lands.

José ruled until 1785, then gave power to his brother Afonso V. Afonso died suddenly, possibly poisoned. A struggle for power followed. By 1794, Henrique I became king. He tried to divide the succession among three groups. Garcia V ignored this and declared himself king in 1805. He ruled until 1830.

André II followed Garcia V. He seemed to bring back the old system of rotating power. André ruled until 1842. Then Henrique II overthrew him. Henrique II gained power by building villages of followers.

André did not accept his defeat. He and his followers moved to Mbanza Mputo, near São Salvador. They continued to claim the throne. King Henrique II ruled from 1842 until 1857.

New Nobles and Trade Changes

In the 1750s, a new group of nobles appeared in Kongo. They were lower-ranking nobles who gained power by taking people and founding new villages. They built fortified places because higher nobles had less control. These nobles often sold slaves, which fed the growing slave trade to the New World. This period was probably the most damaging for Kongo due to the slave trade.

In 1839, Portugal, pressured by Britain, officially ended the slave trade south of the equator. But it continued illegally until the 1920s, first as illegal slave trade, then as contract labor. The slave trade was replaced by trade in goods like ivory, wax, peanuts, and rubber. This new trade changed the economy and politics of Central Africa. Thousands of common people started carrying goods from inland to the coast. They shared in the new wealth. This led to new villages and challenges to old authorities.

During this time, long-distance trade became more important. The new nobles became more stable. They set up markets and protected trade routes. They formed new makanda, which were like trading groups as much as family units. These groups founded villages along trade routes. New stories about the kingdom's founder, Afonso I, said he caused the clans to spread out. These clan histories replaced the kingdom's history in many areas.

Despite rivalries and the kingdom breaking apart, it remained independent into the 1800s. Álvaro Ndongo and Pedro Lelo both claimed the throne. Pedro eventually won with Portuguese help in 1859. When Pedro was crowned Pedro V, he swore to be a vassal of Portugal. Portugal gained control over Kongo and built a fort in São Salvador. In 1866, Portugal removed its soldiers due to high costs. But Pedro continued to rule.

At the Berlin Conference in 1884–1885, European powers divided Central Africa. Portugal claimed most of what was left of Kongo. King Pedro V ruled until 1891. He used Portuguese support to strengthen his power. In 1888, he willingly confirmed Kongo as a Portuguese vassal state. After a revolt against Portugal in 1914, Portugal officially ended the Kingdom of Kongo. Manuel III of Kongo was the ruler at that time. This ended native rule and started direct colonial rule. However, some people still used the title of King of Kongo until at least 1964.

Military Structure

Kongo's army had many archers, who were regular men. It also had a smaller group of heavy infantry, who were nobles. These nobles fought with swords and carried shields. Portuguese documents called them fidalgos (nobles) or adargueiros (shield bearers).

After 1600, civil wars became more common than wars with other states. The government could draft all men during wartime. But only a few actually served. Many others carried supplies. Thousands of women supported the armies. Soldiers were expected to bring two weeks of food. It was hard to keep large armies supplied for long periods. Some Portuguese sources said the King of Kongo had 70,000 soldiers in 1665. But it's more likely armies were 20,000 to 30,000 troops.

Troops were gathered and reviewed on Saint James' Day, July 25. This day also marked tax collection. People celebrated Saint James and Afonso I, who won a battle in 1509.

When the Portuguese arrived, they were added as mercenaries. They used special weapons like crossbows and muskets. At first, they weren't very effective. But by the 1580s, a group of musketeers, made of local Portuguese and mixed-race people, was part of the main Kongo army. Provincial armies also had some musketeers. For example, 360 musketeers fought in the Kongo army against the Portuguese at the Battle of Mbwila.

Political Structure

The basic social unit in Kongo was the vata village, also called libata. Village chiefs, called Nkuluntu, led these villages. Villages had about 100 to 200 people. They moved every ten years because the soil became tired. Land was owned by everyone, and harvests were divided by family size. The Nkuluntu received a special share of the harvest.

Villages were grouped into small states called wene, led by awene or mani. These leaders lived in mbanza, which were larger villages or small towns with 1,000 to 5,000 people. Higher nobles usually chose these leaders. The king also appointed lower officials, usually for three-year terms.

Kongo's larger areas were called provinces. Some big provinces, like Mbamba, were divided into smaller parts. The king appointed the Mwene Mbamba, who became the Duke of Mbamba after the 1590s. The king could technically fire the Mwene Mbamba, but politics often limited this power. Large areas like Mbamba and Nsundi became "Duchies." Smaller ones like Mpemba became "Marquisates." Soyo, a coastal province, became a "County."

Some provinces were controlled by hereditary families. This was true for Mbata and Nkusu. In Mbata's case, it was because the kingdom started as an alliance. In the 1600s, some provinces, like Soyo, were held by the same person for a very long time. Provincial governments still paid taxes to the king.

The Kingdom of Kongo had many provinces. Sources list between six and fifteen main ones. Duarte Lopes, who visited in the late 1500s, named six important provinces: Nsundi, Mpangu, Mbata, Soyo, Mbamba, and Mpemba.

The King of Kongo also had control over other kingdoms. These included Kakongo, Ngoyo, and Vungu to the north. The king's titles, first used by Afonso in 1512, called him "King of Kongo and Lord of the Mbundus." Later titles listed other areas he ruled as "king." These included Ndongo, Kisama, and Matamba to the south.

Royal Council

The King of Kongo ruled with a royal council called the ne mbanda-mbanda. This means "the top of the top." It had twelve members in three groups: bureaucrats, electors, and matrons. Senior officials chose the king, who ruled for life. The electors changed over time. Many kings tried to choose their successor, but it didn't always work. Succession struggles were a big problem in Kongo's history.

Bureaucratic Posts

These four posts did not elect the king. They were:

- Mwene Lumbo (lord of the palace)

- Mfila Ntu (most trusted councilor/prime minister)

- Mwene Vangu-Vangu (lord of deeds or actions/high judge)

- Mwene Bampa (treasurer)

The king appointed these officials. They had a lot of influence on the daily running of the court.

Electors

Another four councilors elected the king and held important jobs:

- Mwene Vunda (lord of Vunda, a small territory with religious duties, who led the electors)

- Mwene Mbata (lord of Mbata province, whose family provided the king's main wife)

- Mwene Soyo (lord of Soyo province, the richest area with the only port and salt access)

- Mwene Mbamba (lord of Mbamba province and army captain-general)

These four men elected the king. The Mwene Vunda and Mwene Mbata were very important in the coronation.

Matrons

The council also had four influential women:

- Mwene Nzimba Mpungu (a queen-mother, usually the king's paternal aunt)

- Mwene Mbanda (the king's main wife, chosen from the Nsaku Lau family)

- The other two posts went to important women, like widowed queens or leaders of former ruling families.

Economic Structure

The main money in Kongo was the shell of a sea snail called nzimbu. These shells were collected from Luanda Island. The king controlled this supply. Only larger shells were used as money. Kongo did not trade for gold or silver.

Nzimbu shells were often put in pots in specific amounts. For example, a pot could hold 40, 100, 250, 400, or 500 shells. For big purchases, there were larger units:

- Funda (1,000 big shells)

- Lufuku (10,000 big shells)

- Kofo (20,000 big shells)

One hundred nzimbu could buy a hen. Three hundred could buy a garden hoe. Two thousand could buy a goat. Slaves were also bought with nzimbu. A female slave cost 20,000 nzimbu, and a male slave cost 30,000. The slave trade grew after contact with Portugal.

The Kongo government saw its land as renda, meaning revenue. They collected a head tax from each villager, possibly paid in goods. This was the basis for the kingdom's money. The king gave titles and income based on this tax. Officials reported yearly to the king for review.

Provincial governors paid part of their tax money to the king. Dutch visitors in the 1640s said this income was 20 million nzimbu shells. The king also collected special taxes and tolls on trade. This included the profitable cloth trade from the "Seven Kingdoms of Kongo dia Nlaza" in the east to the coast.

Royal money also supported the church. For example, Pedro II (1622–1624) used income from various lands to support his royal chapel. Local churches also got money from baptism and burial fees.

When King Garcia II gave Luanda Island to the Portuguese in 1651, Kongo changed its currency. They started using raffia cloth. This cloth was "napkin-sized" and called mpusu. In the 1600s, 100 mpusu could buy one slave. Raffia cloth was also called Lubongo.

Art of the Kongo Kingdom

The people of Kongo are divided into many groups, like the Yombe and Beembe. But they all share the Kikongo language. These groups have similar cultures and create a lot of sculptural art. Their art often shows humans and animals in a very natural way. They paid close attention to muscles, faces, and details like jewelry. Much of this art was made for leaders, including the King of Kongo.

Social Structure

Matrilineal Organization

In the central Bantu groups that made up the Kongo kingdom, status was passed down through the mother's side of the family. Women in these kingdoms could also have important roles in ruling and war. For example, Queen Nzinga, or Njinga, ruled parts of Ndongo and Matamba in the 1600s. She was a strong ruler and war leader. She caused many problems for the Portuguese. She continued fighting them until she died at an old age in 1663.

See also

In Spanish: Reino del Congo para niños

In Spanish: Reino del Congo para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |