Hiram Rhodes Revels facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hiram Revels

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| United States Senator from Mississippi |

|

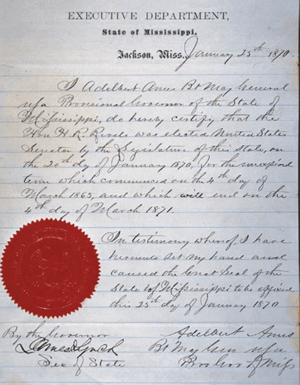

| In office February 25, 1870 – March 3, 1871 |

|

| Preceded by | Albert G. Brown |

| Succeeded by | James L. Alcorn |

| 19th Secretary of State of Mississippi | |

| In office December 30, 1872 – September 1, 1873 |

|

| Governor | Ridgely C. Powers |

| Preceded by | James D. Lynch |

| Succeeded by | Hannibal C. Carter |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hiram Rhodes Revels

September 27, 1827 Fayetteville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | January 16, 1901 (aged 73) Aberdeen, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Phoebe Bass |

| Children | 8 |

| Education |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Unit | Chaplain Corps |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

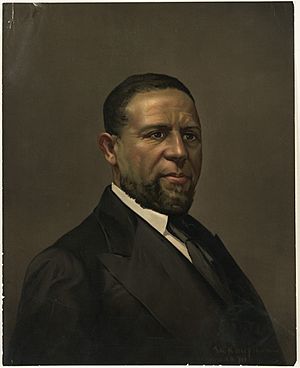

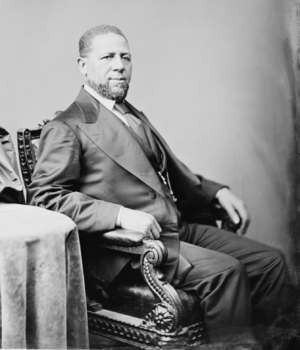

Hiram Rhodes Revels (born September 27, 1827 – died January 16, 1901) was an important American politician, minister, and college leader. He was born free in North Carolina. Before the American Civil War, he lived and voted in Ohio.

In 1870, the Mississippi legislature chose him to be a United States Senator. This was a big deal because he was the first African American to serve in the U.S. Congress. This happened during the time called Reconstruction, after the Civil War.

During the Civil War, Revels helped create two groups of United States Colored Troops. He also worked as a chaplain, which is like a minister for soldiers. After being a senator, Revels became the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College. Today, this school is known as Alcorn State University. It is a historically black college. He led the college from 1871 to 1873 and again from 1876 to 1882. Later in his life, he continued his work as a minister.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Hiram Revels was born free in 1822 in Fayetteville, North Carolina. His family had been free for a long time, even before the American Revolution. His parents had African American, European, and Native American family roots. His mother was also partly from Scotland. His father was a Baptist preacher.

Revels was a cousin to Lewis Sheridan Leary. Leary was one of the men who died during John Brown's famous raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859.

When he was young, a local black woman taught Revels. In 1838, at age 11, he moved to Lincolnton, North Carolina. He lived with his older brother, Elias B. Revels. Hiram learned to be a barber in his brother's shop. Being a barber was a respected job for black Americans back then. It also helped black barbers connect with white people. After his brother Elias died in 1841, Hiram took over the barber shop.

Revels went to school at Beech Grove Quaker Seminary in Union County, Indiana. He also attended the Union Literary Institute. This school was also called the Darke County Seminary.

In 1845, Revels became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME). He traveled and preached in many states. These included Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Tennessee, Missouri, and Kansas. He later said he faced a lot of challenges. In 1854, he was even put in prison in Missouri for preaching to Black people. But he was never hurt. During these years, he was able to vote in Ohio.

From 1855 to 1857, he studied religion at Knox College in Galesburg, Illinois. After that, he became a minister in Baltimore, Maryland. He also worked as the principal of a high school for black students there.

During the American Civil War, Revels served as a chaplain in the United States Army. When the Union Army started forming black regiments, he helped recruit soldiers. He organized two black Union regiments in Maryland and Missouri. He also took part in the Battle of Vicksburg in Vicksburg, Mississippi.

Political Career

In 1865, Revels left the AME Church. He joined the Methodist Episcopal Church. He worked as a pastor in Leavenworth, Kansas, and New Orleans, Louisiana. In 1866, he became a permanent pastor in Natchez, Mississippi. He moved there with his wife and five daughters. He became a leader in the Methodist Church in Mississippi. He kept working as a minister and started schools for black children.

During the Reconstruction period, Revels became involved in politics. In 1868, he was elected as an alderman in Natchez. An alderman is like a city council member. In 1869, he was elected to represent Adams County in the Mississippi State Senate.

Congressman John R. Lynch later wrote about Revels. He said Revels was new to the community. He had not voted or given political speeches before. But he was a black man and a Republican. People thought he was smart and capable.

In January 1870, Revels gave the opening prayer in the state legislature. Lynch said it was a very powerful prayer. It made a deep impression on everyone. This prayer helped Revels become a United States Senator.

Becoming a U.S. Senator

Back then, state legislatures chose U.S. senators. People did not vote for them directly until 1913.

In 1870, the Mississippi legislature elected Revels to the U.S. Senate. He won by a vote of 81 to 15. He was chosen to finish a term that had been empty since the Civil War. The previous senator, Albert G. Brown, left when Mississippi left the Union in 1861.

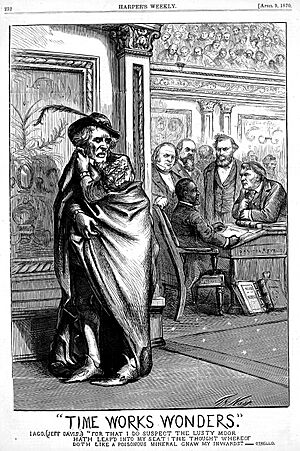

When Revels arrived in Washington, D.C., some Southern Democrats did not want him to join the Senate. There were two days of debate. The Senate rooms were full of people watching this important event. The Democrats used an old Supreme Court decision from 1857, called the Dred Scott Decision. This decision said that people of African ancestry were not citizens. They argued that no black man was a citizen before the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868. So, they said Revels could not be a senator. Senators needed to have been citizens for nine years.

Revels' supporters argued against this. They said that the Civil War and the new amendments had changed everything. They argued that the idea of black people being less than others was no longer part of American law. So, it would be wrong to stop Revels from serving. One Republican Senator said that the opponents were still fighting the "last battle-field" of the war.

Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts said, "The time has passed for argument. Nothing more need be said. For a long time it has been clear that colored persons must be senators." He also said, "All men are created equal, says the great Declaration, and now a great act attests this verity. Today we make the Declaration a reality."

On February 25, 1870, Revels became the first African American to be a U.S. Senator. The vote was 48 to 8. Republicans voted for him, and Democrats voted against him. Everyone in the galleries stood up to watch him take his oath.

As a U.S. Senator

Senator Revels believed in finding common ground and being fair. He strongly supported equal rights for all races. He worked to show other senators that African Americans were capable. In his first speech to the Senate on March 16, 1870, he spoke up for black lawmakers in Georgia. They had been unfairly removed from their jobs. He said, "I maintain that the past record of my race is a true index of the feelings which today animate them. They aim not to elevate themselves by sacrificing one single interest of their white fellow citizens."

He worked on committees for Education and Labor and for the District of Columbia. At that time, Congress managed the District of Columbia. Much of the Senate's work was about Reconstruction. Some politicians wanted to keep punishing former Confederates. But Revels argued for forgiveness. He wanted them to get their full citizenship back if they promised loyalty to the United States.

Revels was a senator for a little over a year. His term was from February 25, 1870, to March 3, 1871. He worked quietly but strongly for equality. He spoke against a plan to keep schools in Washington, D.C., separate by race. He wanted them to be integrated. He also tried to get a young black man into the United States Military Academy. However, the young man was not allowed in. Revels successfully helped black workers who were not allowed to work at the Washington Navy Yard because of their race.

Newspapers in the North praised Revels for his speaking skills. His actions in the Senate, along with other black members of Congress, impressed many. A white Congressman, James G. Blaine, wrote that black members of Congress were "studious, earnest, ambitious men, whose public conduct would be honorable to any race." Revels also supported plans to build roads and levees in Mississippi.

College President and Later Life

After his time as a U.S. Senator ended in 1871, Revels became the first president of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College. This school is now Alcorn State University. It is a historically black college in Claiborne County, Mississippi. He also taught philosophy there. In 1873, Revels took a break from Alcorn. He served as Mississippi's secretary of state for a short time.

He was removed from his job at Alcorn in 1874. This happened because he campaigned against the governor, Adelbert Ames. But in 1876, a new government put him back in charge. He stayed president until he retired in 1882.

On November 6, 1875, Revels wrote a letter to President Ulysses S. Grant. This letter was printed in many places.

Revels continued to be an active minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church. He lived in Holly Springs, Mississippi. He became a leader in the Upper Mississippi District of the church. For a while, he was the editor of the Southwestern Christian Advocate newspaper. This was the newspaper for the Methodist Church. He also taught theology at Shaw College, which is now Rust College. This is another historically black college founded in 1866 in Holly Springs.

Hiram Revels died on January 16, 1901. He was at a church meeting in Aberdeen, Mississippi. He was buried at the Hillcrest Cemetery in Holly Springs, Mississippi.

Legacy

Revels's daughter, Susie Revels Cayton, became an editor for a newspaper in Seattle, Washington. His grandsons included Horace R. Cayton Jr., who wrote a famous book called Black Metropolis. Another grandson, Revels Cayton, was a leader for workers' rights. In 2002, a scholar named Molefi Kete Asante listed Hiram Rhodes Revels as one of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

See also

- List of African-American United States senators

- List of Native Americans in the United States Congress

Additional Reading

- Borome, Joseph A. "The Autobiography of Hiram Rhodes Revels Together with Some Letters by and about Him," Midwest Journal, 5 (Winter 1952–1953), pp. 79–92.

- Foner, Eric. Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders during Reconstruction. 1996. Revised. ISBN: 0-8071-2082-0.

- Gravely, William B., "Hiram Revels Protests Racial Separation in the Methodist Episcopal Church (1876)," Methodist History, 8 (1970), pp. 13–20.

- Hamilton, Brian, "The Monuments We Never Built," Edge Effects, August 22, 2017 http://edgeeffects.net/hiram-revels

- Harris, William C., The Day of the Carpetbagger: Republican Reconstruction in Mississippi, Louisiana State University Press, 1979

- Haskins, James, Distinguished African American Political and Governmental Leaders, Oryx Press. 1999. pp: 216–218.

- Hildebrand, Reginald F., The Times Were Strange and Stirring: Methodist Preachers and the Crisis of Emancipation, Duke University Press, 1995

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |