Paul Robeson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Paul Robeson

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

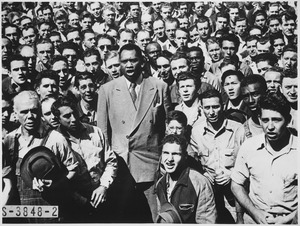

Paul Robeson in 1942

|

|||||||||

| Born |

Paul Leroy Robeson

April 9, 1898 Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.

|

||||||||

| Died | January 23, 1976 (aged 77) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

||||||||

| Resting place | Ferncliff Cemetery | ||||||||

| Education |

|

||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||

| Spouse(s) | |||||||||

| Children | Paul Robeson Jr. | ||||||||

| Relatives | Bustill family | ||||||||

|

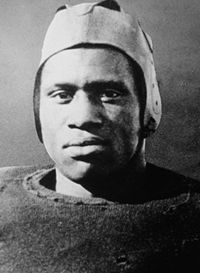

Football career |

|||||||||

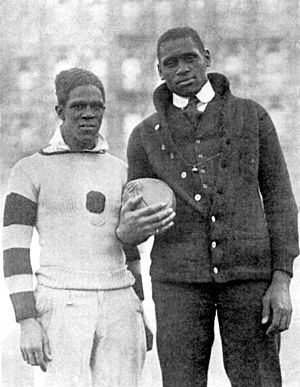

Robeson in football uniform at Rutgers, c. 1919

|

|||||||||

| No. 21, 17 | |||||||||

| Position: | End / tackle | ||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||

| Height: | 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) | ||||||||

| Weight: | 219 lb (99 kg) | ||||||||

| Career information | |||||||||

| High school: | Somerville (NJ) | ||||||||

| College: | Rutgers | ||||||||

| Career history | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Career highlights and awards | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Career NFL statistics | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Player stats at PFR | |||||||||

|

College Football Hall of Fame

|

|||||||||

Paul Leroy Robeson (April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American singer, actor, and activist. He was famous for his amazing talents and his strong beliefs about fairness for all people.

In 1915, Paul Robeson earned a scholarship to Rutgers University. While there, he was a top football player, named an All-American twice. He was also the best student in his graduating class. He later earned a law degree from Columbia Law School while playing in the National Football League (NFL). After law school, he became a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance with his acting.

Robeson performed in Britain, starring in the London show Show Boat in 1928. He lived in London for several years with his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson. He became a well-known concert artist and starred in Othello. He also appeared in films like Sanders of the River (1935) and Show Boat (1936). Robeson started his activism by supporting workers and students in Britain. He also supported the fight against unfair governments during the Spanish Civil War.

After returning to the United States in 1939, Robeson supported the American efforts in World War II. However, his support for civil rights and certain political ideas led to him being watched by the FBI. After the war, his groups faced challenges. He was investigated during a time when people were very worried about certain political views. Because he refused to change his public statements, the U.S. State Department took away his passport. This caused his income to drop a lot.

He moved to Harlem and published a newspaper called Freedom from 1950 to 1955. This paper criticized U.S. policies. Eventually, his right to travel was given back in 1958. This happened because of a U.S. Supreme Court decision.

Between 1925 and 1961, Robeson recorded about 276 songs. His first recordings were the spirituals "Steal Away" and "Were You There" in 1925. Robeson sang many types of music. These included American folk songs, popular tunes, classical music, and European folk songs.

Contents

Paul Robeson's Early Life

Childhood and Family (1898–1915)

Paul Robeson was born in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1898. His parents were Reverend William Drew Robeson I and Maria Louisa Bustill. His mother, Maria, came from the Bustill family, a well-known Quaker family with mixed heritage. His father, William, was from the Igbo people and was born into slavery.

William escaped from a plantation when he was a teenager. He later became a minister in Princeton in 1881. Paul had three older brothers: William Jr., Reeve, and Ben. He also had one older sister, Marian.

In 1900, his father had a disagreement with white supporters of his church. This disagreement seemed to have racial reasons. William resigned in 1901, even though his Black church members supported him. Losing his job meant he had to take low-paying jobs. Three years later, when Paul was six, his mother, who was almost blind, died in a house fire.

His father could no longer afford a house for himself and his two youngest sons, Ben and Paul. They moved into the attic of a store in Westfield, New Jersey. In 1910, William found a stable job as a minister. Paul sometimes filled in for his father during sermons.

In 1912, Paul started attending Somerville High School. He acted in plays like Julius Caesar and Othello. He also sang in the chorus. Paul was excellent at sports, playing football, basketball, baseball, and track. He ignored racial insults he received because of his athletic skills. Before graduating, he won a statewide academic contest. This earned him a scholarship to Rutgers University. He was also named the best student in his class.

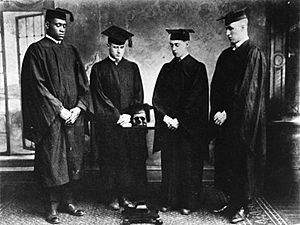

College Years at Rutgers (1915–1919)

In late 1915, Paul Robeson became only the third African-American student at Rutgers. He was the only one there at that time. He tried out for the Rutgers Scarlet Knights football team. His teammates tried to make him quit by playing too roughly. His nose was broken, and his shoulder was dislocated. But the coach, Foster Sanford, saw that Paul would not give up. He announced that Paul had made the team.

Robeson joined the debating team. He sang off-campus to earn money. He also sang informally with the Glee Club on campus. He joined other college sports teams too. As a sophomore, he was benched from a football game. This happened because a Southern team refused to play against Rutgers if Robeson, a Black player, was on the field.

After a great junior year in football, he was praised in The Crisis magazine. They recognized his talents in sports, academics, and singing. Around this time, his father became very ill. Paul took care of him, traveling between Rutgers and Somerville. His father, who was a great inspiration to him, soon passed away. At Rutgers, Robeson spoke about the unfairness of African Americans fighting in World War I but not having equal chances in the U.S.

He finished university with many awards. He won four public speaking contests. He also earned varsity letters in several sports. His football play earned him first-team All-American honors in his junior and senior years. Walter Camp, a famous football coach, called him the greatest end ever. Academically, he was accepted into Phi Beta Kappa, a top honor society. His classmates chose him as the valedictorian. In his graduation speech, he urged his classmates to work for equality for all Americans. At Rutgers, Robeson also became known for his deep, rich singing voice.

Law School and Early Career (1919–1923)

Robeson started at New York University School of Law in 1919. To support himself, he became an assistant football coach at Lincoln University. He then moved to Harlem and transferred to Columbia Law School in February 1920. He was already known for his singing in the Black community. He was chosen to perform at the opening of the Harlem YWCA.

Fritz Pollard recruited Robeson to play for the NFL's Akron Pros while he continued his law studies. In 1922, Robeson took a break from school to act in a play called Taboo. He then sang in a musical before joining Taboo in Britain. After the play, he became friends with Lawrence Brown, a trained musician. Robeson then returned to Columbia Law School. He played for the NFL's Milwaukee Badgers at the same time. He stopped playing football after the 1922 season. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1923.

Becoming a Star and a Voice for Change

Harlem Renaissance and Breakthrough (1923–1927)

Robeson worked briefly as a lawyer. But he decided to leave law because of racism he faced. His wife supported them financially. She worked as a chemist at a hospital. She continued working until 1925, when Paul's acting career took off. They often attended social events at the future Schomburg Center.

In December 1924, he got the main role in Eugene O'Neill's play All God's Chillun Got Wings. The play's opening was delayed because of arguments across the country about its story.

Because of this delay, another play, The Emperor Jones, was brought back. Robeson played the lead role, Brutus. This role was challenging, almost a 90-minute solo performance. But reviews said he was a huge success. His acting success quickly made him famous and part of important social groups.

Lawrence Benjamin Brown, a well-known pianist, met Robeson in Harlem. They improvised a concert of spirituals together. Robeson sang, and Brown played the piano. They loved it so much that they booked a concert at the Provincetown Playhouse. Their performance of African-American folk songs and spirituals was amazing. Victor Records signed Robeson to a contract in September 1925.

London Success and Othello (1928–1932)

In 1928, Robeson played "Joe" in the London production of the musical Show Boat. His singing of "Ol' Man River" became the standard for that song. He was asked to perform for the King at Buckingham Palace. Members of Parliament became his friends. Show Boat ran for 350 shows and was very successful.

Robeson then played Othello in London. He was the first Black actor to play Othello in Britain in many years. He said he moved to London because there was less "racial problem" there. The play received mixed reviews.

While in London, Robeson was one of the first artists to record at the new EMI Recording Studios. These studios later became Abbey Road Studios. He recorded four songs there in September 1931. Robeson returned to Broadway in 1932 for a revival of Show Boat. He received great praise. Later, he was very proud to receive an honorary master's degree from Rutgers.

Learning About Africa and the World (1933–1937)

In 1933, Robeson played Jim in the London production of Chillun for free. Then he returned to the U.S. to star in the film The Emperor Jones. This was the first film to feature an African American in a starring role. His acting in the film was well-received.

In 1934, Robeson studied phonetics and Swahili at the School of Oriental and African Studies. His new interest in African history and culture matched his essay "I Want to be African." In it, he wrote about wanting to connect with his heritage.

His friends in the anti-imperialist movement and British socialists led him to visit the Soviet Union. Robeson traveled there in December 1934. A stop in Berlin showed him the racism in Nazi Germany. When he arrived in Moscow, he said, "Here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life ... I walk in full human dignity."

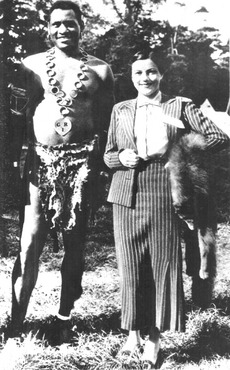

He took on the role of Bosambo in the movie Sanders of the River (1935). He thought it would show a real view of African culture. Sanders of the River made Robeson an international movie star. But the film's portrayal of a colonial African was seen as embarrassing. It also hurt his reputation. The Commissioner of Nigeria protested the film. After this, Robeson became more careful about the roles he chose.

In 1936, he decided to send his son to school in the Soviet Union. He wanted to protect him from racist attitudes. He then played Toussaint Louverture in a play and appeared in films like Song of Freedom and Show Boat in 1936. He also appeared in My Song Goes Forth, King Solomon's Mines, and Big Fella in 1937. In 1938, he was named the 10th most popular star in British cinema.

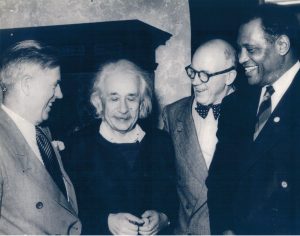

In 1935, Robeson met Albert Einstein. Einstein came backstage after Robeson's concert. They found they both loved music and hated fascism. Their friendship lasted almost twenty years but was not widely known.

Activism and the Spanish Civil War (1937–1939)

Robeson believed the fight against fascism in the Spanish Civil War changed his life. It turned him into a political activist. In 1937, he used his concerts to support the Republican cause. He also helped the war's refugees.

His business agent worried about his political involvement. But Robeson decided that current events were more important than money. In Wales, he honored Welsh people who died fighting for the Republicans. He recorded a message that became famous: "The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative."

He traveled to Spain in 1938. He believed in the cause of the International Brigades. He visited a hospital for wounded soldiers and sang to them. Robeson also visited the battlefront. He boosted the spirits of the Republicans when their victory seemed unlikely. Back in England, he hosted Jawaharlal Nehru to support Indian independence. Nehru spoke about how imperialism was linked to fascism. Robeson decided to focus his career on the struggles of "common people."

With Max Yergan and the Council on African Affairs (CAA), Robeson became a strong supporter of African independence.

Paul Robeson lived in Britain until just before World War II began in 1939. His name was on a list of people to be arrested if Germany occupied Britain.

World War II, Broadway, and Challenges

Supporting the War Effort (1939–1945)

Robeson's last British film was The Proud Valley (1940). It was set in a Welsh coal-mining town. Soon after World War II started, Robeson and his family returned to the United States in 1940. He became America's "no.1 entertainer" with a radio show called Ballad for Americans.

During a tour in 1940, a major Los Angeles hotel would only let him stay because of his race. They charged him a very high price and made him use a fake name. So, every afternoon, he sat in the lobby for two hours. He was widely recognized. He wanted to make sure that other Black people would have a place to stay there in the future. Soon after, Los Angeles hotels removed their rules against Black guests.

Robeson narrated the 1942 documentary Native Land. He later appeared in Tales of Manhattan (1942). He felt this film was "very offensive to my people." After this, he announced he would no longer act in films. This was because of the disrespectful roles offered to Black actors.

Robeson participated in benefit concerts for the war effort. He met two people from the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Later, Robeson played Othello again on Broadway in 1943. He was the first African American to play the role with a white supporting cast on Broadway. During this time, he also tried to convince baseball owners to allow Black players in Major League Baseball. He toured North America with Othello until 1945.

Robeson also supported China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In 1940, a Chinese activist taught him the patriotic song "Chee Lai!" ("Arise!"). This song is now known as the March of the Volunteers. Robeson sang the song at a concert in New York City. He recorded it in both English and Chinese in 1941. The song later became the National Anthem of the People's Republic of China.

Facing Challenges and Restrictions (1946–1949)

In 1946, Robeson met with President Truman. He told Truman that if he did not pass laws to stop lynching, "the Negroes will defend themselves." Truman ended the meeting quickly. He said it was not the right time for anti-lynching laws. Robeson then publicly asked all Americans to demand civil rights laws from Congress. Robeson started the American Crusade Against Lynching in 1946.

Around this time, Robeson believed that trade unions were key to civil rights. He became a strong supporter of union activists. Robeson was later questioned about his connection to the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). He said he was not a member. However, two groups Robeson was involved with were placed on a list of "subversive organizations."

He was called before a Senate committee. When asked about his ties to the Communist Party, he refused to answer. He said, "Some of the most brilliant and distinguished Americans are about to go to jail for the failure to answer that question, and I am going to join them, if necessary."

In 1948, Robeson strongly supported Henry A. Wallace for President. Robeson traveled to the Deep South to campaign, even though it was dangerous for him. The next year, his concerts were canceled because of the FBI. He had to go overseas to work. While on tour, he spoke at the World Peace Council. His speech was reported as saying America was like a Fascist state. He denied this, but the reported speech made many see him as an enemy.

On June 20, 1949, Robeson spoke at the Paris Peace Congress. He said that Americans, both white workers and Black people, built the wealth of America. He said they were determined to share it equally. He stated they would not make war on anyone, especially the Soviet Union. He said they wanted peace and friendship among all nations. Because of this, he was criticized in the U.S. press.

To politically isolate Robeson, a committee called HUAC asked Jackie Robinson to comment on Robeson's Paris speech. Robinson said Robeson's statements, "if accurately reported," were "silly." Days later, a Robeson concert in New York City was announced. Local newspapers criticized using their community to support "subversives." This led to the Peekskill Riots. Violent protests shut down a Robeson concert on August 27, 1949. They also caused trouble after a replacement concert eight days later.

Passport Denied and Blacklisted (1950–1955)

In 1950, a book about college football did not even list Robeson as having played for Rutgers. Months later, NBC canceled Robeson's appearance on Eleanor Roosevelt's TV show. Then, the State Department took away Robeson's passport. They issued a "stop notice" at all ports. This meant he could not leave the United States. He had less freedom to speak about his strong support for the independence of African nations. When Robeson asked why his passport was denied, he was told his criticisms of how Black people were treated in the U.S. should not be shared in other countries.

In 1950, Robeson co-founded a monthly newspaper called Freedom. It shared his views and those of his friends. Most issues had a column by Robeson on the front page. In the last issue in 1955, an article described the fight to get his passport back. It asked for support from Black organizations. It said that Black people and all Americans who wanted peace had a stake in Robeson's passport case.

In 1951, an article called "Paul Robeson – the Lost Shepherd" was published. It was later thought to be written by J. Edgar Hoover and the U.S. State Department. They arranged for it to be printed and given out in Africa. This was to damage Robeson's reputation and reduce the popularity of his ideas there. Another article criticized Robeson and the Communist Party USA.

In December 1951, Robeson and William L. Patterson presented a petition to the United Nations. It was called "We Charge Genocide". The document said the U.S. government was "guilty of genocide" by not stopping lynching in the United States. The UN did not officially acknowledge the petition. It was mostly ignored or criticized in the mainstream U.S. press.

In 1952, Robeson received the International Stalin Prize from the Soviet Union. He accepted the award in New York because he could not travel to Moscow. In April 1953, after Stalin's death, Robeson wrote an article praising Stalin. He called him dedicated to peace and a guide to the world. Robeson's opinions about the Soviet Union kept his passport out of reach. This stopped him from returning to entertainment and the civil rights movement. He believed the Soviet Union helped keep political balance in the world.

In a symbolic act against the travel ban, labor unions in the U.S. and Canada held a concert in May 1952. It was at the International Peace Arch on the border. Robeson performed a second concert there in 1953. Two more concerts took place over the next two years. During this time, Robeson recorded radio concerts for supporters in Wales.

Passport Restored (1956–1957)

In 1956, Robeson was called before HUAC again. He refused to sign a paper saying he was not a Communist. In his testimony, he used his Fifth Amendment right. He refused to share his political beliefs. When asked why he did not stay in the Soviet Union, he said, "because my father was a slave and my people died to build [the United States and], I am going to stay here, and have a part of it just like you and no fascist-minded people will drive me from it!" He stated that whether he was a Communist or not was not important. The question was whether American citizens could have their constitutional rights, no matter their political beliefs.

Because of his political views, his recordings and films were removed from public access. He was widely criticized in the U.S. press. During the Cold War, it became very hard to hear Robeson sing on the radio or buy his music in the United States.

In 1956, a record company in the United Kingdom released a song by Robeson. It was the labor anthem "Joe Hill". In 1956, after public pressure, Robeson was allowed a one-time travel exemption. He performed two concerts in Canada in February.

Still unable to perform abroad in person, Robeson sang for a London audience on May 26, 1957. He used the newly completed transatlantic telephone cable. In October, he sang to 5,000 people in Wales using the same technology.

In 1956, a Soviet leader criticized Stalin. This made Robeson stop praising Stalin, but he still praised the Soviet Union. That year, Robeson and his friend W. E. B. Du Bois compared the anti-Soviet uprising in Hungary to people who overthrew the Spanish Republican Government. They supported the Soviet invasion that stopped the revolt.

Robeson's passport was finally given back in 1958. This happened because of a U.S. Supreme Court decision. The court ruled that denying a passport without a fair process was against the Constitution.

Later Years and Legacy

Comeback Tours (1958–1960)

In 1958, Robeson's book Here I Stand was published. It was like his personal statement.

Europe

Robeson started a world tour, using London as his base. In 1958, he gave 28 performances across the UK. In April 1959, he starred in a production of Othello in Stratford-upon-Avon. In Moscow in August 1959, he received a huge welcome. He sang classic Russian songs and American favorites. Robeson then flew to Yalta to rest and spend time with Nikita Khrushchev.

On October 11, 1959, Robeson sang at St Paul's Cathedral in London. He was the first Black performer to sing there. On a trip to Moscow, Robeson had dizzy spells and heart problems. He was in the hospital for two months. He recovered and returned to the UK.

In 1960, Robeson gave his last concert in Great Britain. He sang to raise money for the Movement for Colonial Freedom.

Australia and New Zealand

In October 1960, Robeson went on a two-month concert tour of Australia and New Zealand. He mainly did this to earn money. While in Sydney, he was the first major artist to perform at the construction site of the future Sydney Opera House. After a show in Brisbane, he went to Auckland. There, Robeson spoke about his support for certain political ideas. He also spoke against the unfairness faced by the Māori people and efforts to harm their culture. He publicly stated that "the people of the lands of Socialism want peace dearly."

During the tour, he met activists who told him about the struggles of the Australian Aborigines. Robeson then demanded that the Australian government give Aborigines citizenship and equal rights. He said there was no such thing as a "backward" human being. He said there was only a society that called them backward.

Robeson left Australia as a respected, though sometimes controversial, figure. His support for Aboriginal rights had a big impact in Australia for the next ten years.

Final Years (1965–1976)

Paul Robeson's wife, Essie, passed away in December 1965. She had been his spokesperson for many years. Robeson then moved in with his son's family in New York City. He was rarely seen outside his Harlem apartment. His son told the press that his father's health did not allow him to perform or answer questions. In 1968, he moved to his sister's home in Philadelphia.

Many celebrations were held in Robeson's honor over the next few years. These included events at places that had once avoided him. But he saw few visitors and made few public statements. He felt his past actions "spoke for itself."

In 1973, a tribute was held for his 75th birthday at Carnegie Hall. He could not attend, but a taped message from him was played. He said: "Though I have not been able to be active for several years, I want you to know that I am the same Paul, dedicated as ever to the worldwide cause of humanity for freedom, peace and brotherhood."

Paul Robeson's Legacy and Honors

Early in his life, Robeson was a very important part of the Harlem Renaissance. His achievements in sports and culture were even more impressive because of the racism he overcame. Robeson helped bring Negro spirituals into mainstream American music. He was among the first artists to refuse to perform for audiences that were separated by race.

In 1945, he received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP. Several public places he was connected with have been recognized or named after him. His efforts to end Apartheid in South Africa were honored after his death in 1978. Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist won an Academy Award for best short documentary in 1980. In 1995, he was named to the College Football Hall of Fame. For his 100th birthday, he received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award. He also got a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Robeson is also a member of the American Theater Hall of Fame.

As of 2011, Robeson's run in Othello was the longest-running Shakespeare play ever on Broadway. He received a Donaldson Award for his performance. His portrayal of Othello is seen as a highlight in 20th-century Shakespearean theater. In 1930, while performing Othello in London, he was painted by British artist Glyn Philpot. This portrait was later lost but found again in 2022.

Robeson's historical papers are kept at the Academy of Arts, Howard University, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. In 2010, his granddaughter started a project at Swansea University. It aims to create an online learning resource in his memory.

In 1976, the apartment building in Harlem where Robeson lived was renamed the Paul Robeson Residence. It was also declared a National Historic Landmark. In 1993, it became a New York City landmark. Edgecombe Avenue was later also named Paul Robeson Boulevard.

In 1978, a Soviet news agency announced that a new tanker ship was named Paul Robeson in his honor. The ship's crew even created a Robeson museum on board. After Robeson's death, a street in East Berlin was renamed Paul-Robeson-Straße. This street name remains in Berlin today. An East German stamp with Robeson's face was issued.

In 2001, a public artwork by Allen Uzikee Nelson was dedicated in Washington, D.C. It was called (Here I Stand) In the Spirit of Paul Robeson. In 2002, a blue plaque was placed on the house in Hampstead, London, where Robeson lived. On May 18, 2002, a concert celebrated the 50th anniversary of Robeson's concert across the Canadian border.

In 2004, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp honoring Robeson. In 2006, a plaque was unveiled in his honor at SOAS University of London. In 2007, a company released a DVD set of Robeson's films. In 2009, Robeson was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.

The main library at Rutgers University-Camden is named after Robeson. So is the campus center at Rutgers University-Newark. The Paul Robeson Cultural Center is at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

In 1972, Penn State created a cultural center on its campus. Students and staff chose to name it after Robeson. A street in Princeton, New Jersey, is named after him. Also, a block of Davenport Street in Somerville, New Jersey, is called Paul Robeson Boulevard. In West Philadelphia, the Paul Robeson High School is named after him. To celebrate 100 years since Robeson's graduation, Rutgers University named an open-air plaza after him in 2019. The plaza has black granite panels with details of Robeson's life.

On March 6, 2019, the city council of New Brunswick, New Jersey, approved renaming Commercial Avenue to Paul Robeson Boulevard.

A dark red heirloom tomato from the Soviet Union was given the name Paul Robeson.

Paul Robeson's Films

- Body and Soul (1925)

- Camille (1926)

- Borderline (1930)

- The Emperor Jones (1933)

- Sanders of the River (1935)

- Show Boat (1936)

- Song of Freedom (1936)

- Big Fella (1937)

- My Song Goes Forth (1937)

- King Solomon's Mines (1937)

- Jericho/Dark Sands (1937)

- The Proud Valley (1940)

- Native Land (1942)

- Tales of Manhattan (1942)

- The Song of the Rivers (1954)

Paul Robeson's Music Recordings

Paul Robeson had a very long career recording music. Websites list about 66 albums and 195 singles by him.

See also

In Spanish: Paul Robeson para niños

In Spanish: Paul Robeson para niños

- Freedom (American newspaper)

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |