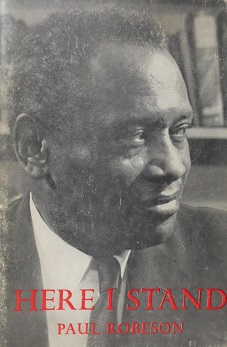

Here I Stand (book) facts for kids

First edition

|

|

| Author | Paul Robeson |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Othello Associates |

|

Publication date

|

1958 |

| Pages | 128 |

Here I Stand is a book written in 1958 by Paul Robeson. He worked with Lloyd L. Brown on it. While Robeson wrote many articles and speeches, Here I Stand is his only book. It's like a mix of his life story and his ideas for change. Othello Associates published the book. Robeson dedicated it to his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson.

Contents

About the Book's Message

In the book's opening, Robeson talks about his background. He explains his strong dedication to helping Black people in America gain freedom. He wants the book to share his thoughts and beliefs. It is not just a story about his life.

He also shares memories from his childhood and how he grew up.

Paul Robeson's Journey and Beliefs

Robeson describes how he became a famous actor and singer. He moved from America to England, which became his home from 1927 to 1939. While there, he learned a lot about African cultures and languages.

In 1934, he visited the Soviet Union. He said he felt no racism there. He believed that certain ideas, like socialism, could help countries become free from colonial rule. Socialism is a belief in sharing resources and working together for everyone's good. Robeson stated he never joined the Communist party.

He also talks about a speech he gave in Paris in 1948. He told Black people that fighting for a "free world" must start at home. He fully agreed with the Ten Principles of Bandung. These were ideas for cooperation among newly independent nations.

Connecting with People and Fighting for Freedom

While in England, Robeson felt a strong connection to ordinary people. He believed that all people are connected. This belief existed alongside his deep care for his own race. He first felt this connection through music and song.

As fascism grew in Europe in the 1930s, he realized something important. The fight for Black freedom was linked to the fight against fascism. He also explains how he stayed connected with people worldwide. This was even when the State Department took away his passport. He describes how the movie The Song of the Rivers was made during this time.

Our Right to Travel Freely

Robeson's passport was taken away in 1950. He believed this happened because he spoke up for Black people and their freedom. He saw himself as fighting for freedom and being truly "American." He thought the State Department and John Foster Dulles were acting "un-American."

He argued that the right to travel is a key part of being a full citizen. He mentioned Ira Aldridge, a Black actor. Aldridge could only achieve great artistic success by traveling abroad. Robeson also spoke about W. E. B. Du Bois, whose passport was also taken. He felt Du Bois's presence at international meetings would have helped the United States.

The Time for Change is Now

Robeson did not believe in waiting for change. He rejected segregation (keeping people apart by race). He also rejected gradualism (making changes slowly). He demanded full citizenship and equality for Black people right away.

He saw people in newly free nations in Africa and Asia as natural friends. They were allies in the fight for Black rights. He knew he could not change individual prejudices. But he demanded that racist laws limiting Black equality must end.

The Power of Black Action

Robeson believed that most Americans would support Black people. This would happen when Black people claimed their rights with "earnestness, dignity, and determination." He said Black people had the power of numbers, organization, and spirit to succeed now.

He pointed to important examples of action. These included the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington D.C. in 1957. He also mentioned events in Little Rock and Montgomery. Robeson called for everyone to work together and for strong leaders.

Looking to the Future

In the end of the book, Robeson feels hopeful. He sees progress, like the events in Little Rock. He also mentions the launch of Sputnik. This space satellite, he felt, sent a message to work for peace. He believed that racism was the real enemy.

Later Thoughts and Ideas

The 1971 edition of the book includes extra writings. One is by Benjamin C. Robeson, titled "My Brother, Paul." There is also a statement from Paul Robeson after he got his passport back.

Robeson also wrote about the importance of the pentatonic scale in music. He believed he found common links in folk songs through this scale. He thought this pattern also appeared in Chinese and African languages.

A later statement from August 1964 reviews the progress in the fight for Black freedom. It ends with a hopeful message: "we surely can sing together: 'Thank God Almighty, we're moving!'"

About the 1971 Edition

In 1971, Lloyd L. Brown added a new introduction to the book. He wrote it when the book was reprinted. He remembered how difficult things were for Robeson. His rights as a citizen were taken away, even though he was never charged with breaking any law. Brown said Robeson's book is very important to understand his views.

Brown also described how the book was first received. Most American newspapers ignored it. They did not even mention it in their new book sections. But Black newspapers, left-wing papers, and foreign newspapers did cover it. Brown saw Robeson as a "Great Forerunner" for Black liberation.

What the Book Means

The book's title, Here I Stand, reminds people of Martin Luther's famous statement. He said "Here I stand" when facing powerful authorities.

The book is partly about Robeson's life and partly a plan for action. Robeson says his main loyalty is to "his own people." He believed that trade unions and the Black church were leading the way. He called himself a "scientific socialist." This term was made famous by Friedrich Engels.

Robeson believed the time for Black freedom was now. He called for unity. He also said that Black leaders, not outside groups, should guide this freedom movement. While many white newspapers ignored the book, the Black press did not. "I Am Not a Communist Says Robeson" was a headline in The Afro-American. The first edition sold out in six weeks. This helped Robeson become active again after his travel ban.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |