Claude McKay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Claude McKay

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Festus Claudius McKay September 15, 1890 Clarendon Parish, Jamaica |

| Died | May 22, 1948 (aged 57) Chicago, Illinois |

| Occupation | Writer, poet, journalist |

| Language | English |

| Education | Kansas State College, Tuskegee Institute |

| Period | Harlem Renaissance |

| Notable works | Songs of Jamaica (1912); "If We Must Die" (1919); Harlem Shadows (1922); Home to Harlem (1928); A Long Way from Home (1937) |

| Notable awards | Harmon Gold Award |

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ (born September 15, 1890 – died May 22, 1948) was an important Jamaican-American writer and poet. He was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a time when Black artists and writers created amazing works in the 1920s.

Born in Jamaica, McKay first came to the United States for college. Here, he read a book by W. E. B. Du Bois that made him interested in fighting for social justice. In 1914, he moved to New York City. In 1919, he wrote "If We Must Die", one of his most famous poems. This poem was a powerful response to the unfair racial violence happening after World War I.

McKay was mainly a poet, but he also wrote several novels. His book Home to Harlem (1928) was a bestseller and won an award for literature. He also wrote Banjo (1929) and Banana Bottom (1933). Besides novels and poetry, McKay wrote short stories, two books about his own life, and a book about Harlem's history. His 1922 poetry book, Harlem Shadows, was one of the first books published during the Harlem Renaissance.

McKay became interested in Fabian socialism (a type of social reform) when he was a teenager. In the U.S., he joined groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which welcomed Black members. He believed in fighting for the rights of Black people. He also worked as an editor for The Liberator magazine. In 1922–1923, he traveled to the Soviet Union, where he was celebrated by the Communist Party. However, he soon realized he was being used for political reasons. He then left for Western Europe.

After returning to Harlem in 1934, McKay often disagreed with some political groups. His book A Long Way From Home was criticized by these groups. Later in his life, in the mid-1940s, he became ill. He was helped by a friend and later converted to Catholicism.

Contents

Biography

Early life in Jamaica

Claude McKay was born on September 15, 1890, in Nairne Castle, Jamaica. He was the youngest of eight children. His parents, Thomas and Hannah, were respected farmers and active members of the Baptist church. Thomas, his father, was from the Ashanti people, and Hannah, his mother, had ancestors from Madagascar. Claude remembered his father sharing stories about Ashanti customs.

When he was about nine, McKay went to live with his older brother, Uriah Theodore, who was a teacher and amateur journalist. His brother helped him get a good education. McKay loved to read classical and British literature, as well as philosophy and science. He started writing his own poems at age 10.

As a teenager, McKay worked as a carriage and cabinet maker for two years. In 1907, he met Walter Jekyll, a philosopher who became his mentor. Jekyll encouraged McKay to focus on his writing and to write in his local language, Jamaican Patois. Jekyll even helped McKay publish his first book of poems, Songs of Jamaica, in 1912. These were the first poems published in Jamaican Patois. McKay's next book, Constab Ballads (1912), was about his short time working in the police force in 1911.

In his poem "The Tropics in New York", McKay wrote about missing the Caribbean. The poem is set in New York, where he lived as a worker. The fruits he saw in New York made him long for Jamaica. He imagined the colorful fruits as part of the New York city, reminding him of his home.

First stay in the US

McKay moved to the U.S. in 1912 to attend Tuskegee Institute. He was shocked by the strong racism he faced in Charleston, South Carolina. Many public places were separated by race. This experience made him want to write more poetry. He didn't like the strict rules at Tuskegee and soon left. He then studied at Kansas State Agricultural College. There, he read The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois, which greatly influenced his interest in fighting for Black rights.

In 1914, McKay decided he didn't want to be an agronomist (a plant scientist). He moved to New York City and married his childhood sweetheart, Eulalie Imelda Edwards. However, after only six months, his wife returned to Jamaica, where their daughter Ruth was born. McKay never met his daughter. During this time, McKay worked various jobs, including managing a restaurant and working as a waiter.

In 1917, McKay published two poems under a pen name. In 1919, he met Crystal and Max Eastman, who published The Liberator magazine. McKay became a co-editor there until 1922. As co-editor, he published "If We Must Die", one of his most famous poems. This was during a time of intense racial violence against Black people in America.

During this period, McKay joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). He also became involved with a group of Black activists who wanted Black people to have more control over their own lives. These writers included Cyril Briggs and Wilfred Domingo. They worked for Black self-determination within a socialist movement. They even started a group called the African Blood Brotherhood. In late 1919, McKay traveled to London, possibly because the U.S. government was targeting activists.

Time in the United Kingdom

In London, McKay spent time with socialist and literary groups. He often visited two clubs: a soldiers' club and the International Socialist Club. He also joined the Rationalist Press Association, a group that published books on reason and science. During this time, he became even more committed to socialism and read a lot of Karl Marx's writings.

At the International Socialist Club, McKay met many important figures in the socialist movement. He was soon asked to write for Workers' Dreadnought, a magazine run by Sylvia Pankhurst. He became a paid journalist for the paper. He also had some of his poems published in the Cambridge Magazine.

When Sylvia Pankhurst was arrested for publishing articles that might cause unrest, McKay's rooms were searched. He was likely the author of an article that was used in the case against Workers' Dreadnought.

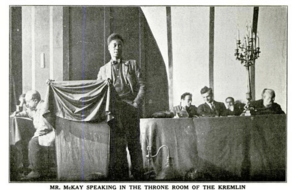

Trip to Russia

In November 1922, McKay was invited to Russia by the Communist Party. He traveled there to attend a big meeting called the Fourth Congress of the Communist International in Petrograd and Moscow. He paid for his trip by selling copies of his book Harlem Shadows and working as a stoker (someone who shovels coal) on a ship. In Russia, he was welcomed with great excitement, almost like a rock star.

Later travels

McKay wrote about his travels in Morocco in his 1937 autobiography, A Long Way from Home. Before this trip, he went to Paris, where he became very sick and needed to go to the hospital. After getting better, he continued traveling for 11 years across Europe and parts of North Africa. During this time, he published three novels. The most famous was Home to Harlem, published in 1928. This novel showed a detailed picture of Black urban life.

He also wrote Banana Bottom during these 11 years. In this book, McKay explored his main idea: how Black people search for their own cultural identity in a society dominated by white culture. His final year abroad saw the creation of Gingertown, a collection of 12 short stories. Half of these stories were about his life in Harlem, and the others were about his time in Jamaica.

Later life

McKay became an American citizen in 1940. In 1943, he started "Cycle Manuscript", a collection of 54 poems, mostly sonnets, often with political themes. This collection was not published during his lifetime but was included in his later Complete Poems. In the mid-1940s, McKay became interested in Catholicism. He studied Catholic social ideas and was baptized in Chicago in October 1944. He wrote to a friend that he wanted to be "intellectually honest and sincere" about his conversion. He also assured his friend that he was "not less the fighter."

In 1946, he moved to Albuquerque and then San Francisco for his health, before returning to Chicago in 1947. On May 22, 1948, Claude McKay died from a heart attack in Chicago at age 58. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery in Queens, New York.

Literary movements and traditions

McKay became a well-known poet during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. During this time, his poems challenged white authority and celebrated Jamaican culture. He also wrote stories about the challenges of being a Black man in Jamaica and America. McKay openly disliked racism, believing it made people narrow-minded and hateful.

His novel Home to Harlem (1928) was first criticized by some, like W. E. B. Du Bois, for showing a negative side of Harlem. However, McKay was later praised as a powerful writer in the Harlem Renaissance.

One of his works that fought against racial unfairness is the poem "If We Must Die" (1919). This poem urged Black people to fight with courage against those who would harm them.

McKay often used the sonnet form, which was an older style of poetry. Many modern writers at the time didn't like this, but McKay found it perfect for sharing his ideas. He created many important modern sonnets despite their criticism.

He also critically viewed how some modernist painters showed African subjects. He felt that stereotyping African physical forms, even by accident, reminded him of the colonialism he grew up with in Jamaica. McKay even posed for a Cubist painter, André Lhote, when he needed money. Through this experience, McKay saw how the power difference between European white culture and people of Afro-Caribbean descent could play out between an artist and their subject. He wrote about this experience in his works, shining a light on a part of modern art that he felt was unfair.

Political views and social activism

McKay joined the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) in 1919 while working in a factory. He believed that some political groups in the U.S. were using Black people for their own goals, rather than truly helping them. During his visit to the Soviet Union, he gave a speech called "Report on the Negro Question." In it, he argued that America was not fully accepting of Black Communists. After this speech, the Communist Party in Russia asked him to write a book about this idea. He wrote Negry v Amerike in 1923, which was originally in Russian and not translated into English until 1979.

McKay's political and social views were clear in his writings. In his 1929 book, Banjo: a Story Without a Plot, he included strong comments about how Western societies often cared more about business than about racial justice.

Personal life

Later years and death

Less than twenty years before he died, McKay largely moved away from non-religious ideas and became interested in Catholicism. He worked with Harlem's Friendship House, a Catholic group that promoted good relationships between different races. McKay moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he joined a Catholic organization as a teacher. By the mid-1940s, McKay had health problems and suffered from several illnesses. He died of heart failure in 1948.

Works

In 1928, McKay published his most famous novel, Home to Harlem. It won the Harmon Gold Award for Literature. The novel showed street life in Harlem and had a big impact on Black thinkers in the Caribbean, West Africa, and Europe.

Home to Harlem became very popular, especially among people who wanted to learn about Harlem nightlife. McKay tried to capture the energetic spirit of "uprooted black travelers" in his novel. In Home to Harlem, McKay looked among everyday people to find a unique Black identity.

McKay's other novels were Banjo (1929) and Banana Bottom (1933). Banjo shows how the French treated people from their African colonies and focuses on Black sailors in Marseilles. Aimé Césaire said that in Banjo, Black people were described truthfully. Banana Bottom, McKay's third novel, shows a Black person searching for their cultural identity in a white society. The book talks about the racial and cultural tensions beneath the surface.

McKay also wrote a collection of short stories, Gingertown (1932). He wrote two books about his own life: A Long Way from Home (1937) and My Green Hills of Jamaica (published after he died in 1979). He also wrote a non-fiction book about Harlem's social history called Harlem: Negro Metropolis (1940). His Selected Poems (1953) was a collection he put together in 1947, but it was published after his death.

Legacy

In 1977, the government of Jamaica named Claude McKay the national poet. They also gave him the Order of Jamaica award for his important contributions to literature.

In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Claude McKay on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans. McKay is seen as the "most important left-wing Black thinker of his time." His work greatly influenced a generation of Black authors, including James Baldwin and Richard Wright.

Claude McKay's poem "If We Must Die" was read in the film August 28: A Day in the Life of a People. This film was shown when the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture opened in 2016.

Awards

- Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences, Musgrave Medal, 1912, for his poetry books Songs of Jamaica and Constab Ballads.

- Harmon Foundation Award for great writing, NAACP, 1929, for Harlem Shadows and Home to Harlem.

- James Weldon Johnson Literary Guild Award, 1937.

- Order of Jamaica, 1977.

Selected works

Poetry collections

- Songs of Jamaica (1912)

- Constabe Ballads (1912)

- Spring in New Hampshire and Other Poems (1920)

- Harlem Shadows (1922)

- The Selected Poems of Claude McKay (1953)

- Complete Poems (2004)

Fiction

- Home to Harlem (1928)

- Banjo (1929)

- Banana Bottom (1933)

- Gingertown (1932)

- Harlem Glory (1990) – written around 1940

- Amiable with Big Teeth (2017) - written in 1941

- Romance in Marseille (2020) - written around 1933

Non-fiction

- A Long Way from Home (1937)

- My Green Hills of Jamaica (1979, written 1946)

- Harlem: Negro Metropolis (1940)

- The Passion of Claude McKay: Selected Poetry and Prose, 1912-1948, edited by Wayne F. Cooper (includes letters and essays)

Unknown manuscript

In 2012, a previously unknown manuscript of a novel by McKay from 1941 was confirmed to be real. The novel is called Amiable With Big Teeth: A Novel of the Love Affair Between the Communists and the Poor Black Sheep of Harlem. It was found in 2009 by a student named Jean-Christophe Cloutier at Columbia University. The novel is about the ideas and events happening in Harlem just before World War II, like Benito Mussolini's invasion of Ethiopia.

Professor Cloutier and his advisor, Professor Brent Hayes Edwards, confirmed the manuscript was real. They received permission to publish the novel, which is a satire (a humorous criticism) set in 1936. It was published in February 2017.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Claude McKay para niños

In Spanish: Claude McKay para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |