Civil Rights Congress facts for kids

| Predecessor |

|

|---|---|

| Founded | 1946 |

| Founder | William Patterson |

| Dissolved | 1956 |

| Type | Non-profit organization |

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was an organization in the United States that fought for the rights of citizens. It was formed in 1946 and ended in 1956. The group was created by merging three other organizations: the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties, and the National Negro Congress.

The CRC's main goal was to defend people's rights, especially African Americans who faced unfair treatment. Starting around 1948, the group became famous for helping Black people who were sentenced to death. They wanted to show the world how unfair the justice system could be.

At its most popular in 1950, the CRC had 60 local groups, or chapters, across the country. These chapters worked on local problems. Most were on the East and West coasts of the U.S.

Contents

What the CRC Did

The CRC used two main strategies to fight for justice. They used the court system (litigation) and held public protests. They also worked hard to tell the public about cases of racial injustice, especially in the southern states.

Many of the cases they highlighted involved Black people who were given the death penalty. At that time in the South, Black people were often not allowed to vote. Because only voters could be on a jury, this meant that juries were made up of only white people. This made it very difficult for Black people to get a fair trial.

The CRC was very good at getting people in other countries to pay attention to these issues. Sometimes, people from around the world would protest to the U.S. president and Congress. The CRC also helped with legal appeals to try to get sentences changed.

The CRC was sometimes seen as a competitor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), another important civil rights group. Both groups worked on similar issues, but they sometimes had different ideas on how to solve problems.

Famous Legal Cases

The CRC helped people they believed were wrongly accused. They used these cases to raise awareness about injustice through demonstrations and public events.

Resisting Anti-Communist Laws

The CRC was against laws like the 1940 Smith Act and the 1950 McCarran Act. These laws gave the government more power to go after people who disagreed with it. The CRC often helped people who were targeted by a government group called the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC).

They also defended Harry Bridges, a union leader. The government tried to punish him for his political beliefs. The CRC helped him fight his case in court.

Fighting the Death Penalty in the South

The Case of Rosa Lee Ingram

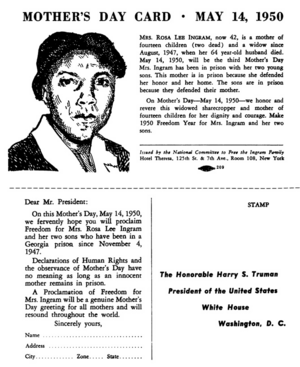

The CRC's first major national campaign was for Rosa Lee Ingram and her two teenage sons. They were sharecroppers in Georgia. In 1947, they were accused of murdering their white neighbor after an argument.

After a one-day trial in 1948, an all-white jury found them guilty. They were all sentenced to death. The CRC and the NAACP worked to get them a new hearing. The judge did not give them a new trial, but he did change their sentence from death to life in prison.

The CRC and NAACP sometimes disagreed on how to handle the case. The NAACP focused on the legal work, while the CRC focused on telling the public about the case. The CRC held rallies every Mother's Day to support Rosa Lee Ingram. In 1959, after being called "model prisoners," Ingram and her sons were released.

Martinsville Seven and Willie McGee

The CRC also fought for the Martinsville Seven. These were seven Black men in Virginia who were all sentenced to death in 1949. They were accused of a very serious crime against a white woman. At the time in Virginia, only Black men were given the death penalty for this type of accusation.

The NAACP's lawyer refused to work with the CRC on this case. This was because the government had called the CRC a "subversive" group, meaning they thought it was trying to harm the government.

The CRC also helped Willie McGee in Mississippi, who was also sentenced to death after a similar accusation. The CRC created national attention for both cases. Sadly, their appeals failed. The Martinsville Seven were executed in February 1951, and Willie McGee was executed in May 1951.

Government Pressure and the End of the CRC

During a time in American history called the Red Scare, many people were afraid of communism. Because some CRC leaders were members of the Communist Party, the U.S. government targeted the group. The Attorney General called the CRC a "communist front," meaning he believed it was secretly controlled by communists.

The government made it difficult for the CRC to operate. The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) investigated the group. The FBI also spied on the CRC and its members, including famous people like singer Lena Horne and actor Paul Robeson.

In 1956, the government officially labeled the CRC a communist group. With so much pressure from the government, the members of the Civil Rights Congress voted to end the organization that same year.

See also

- O. John Rogge